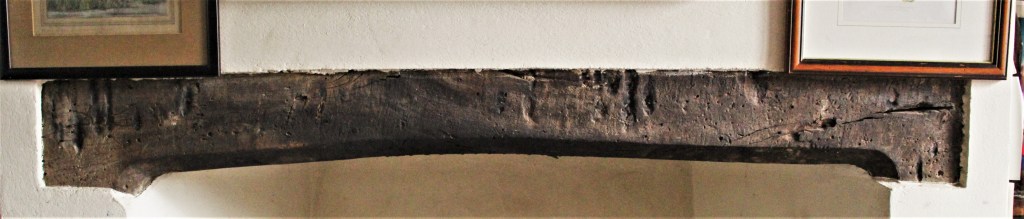

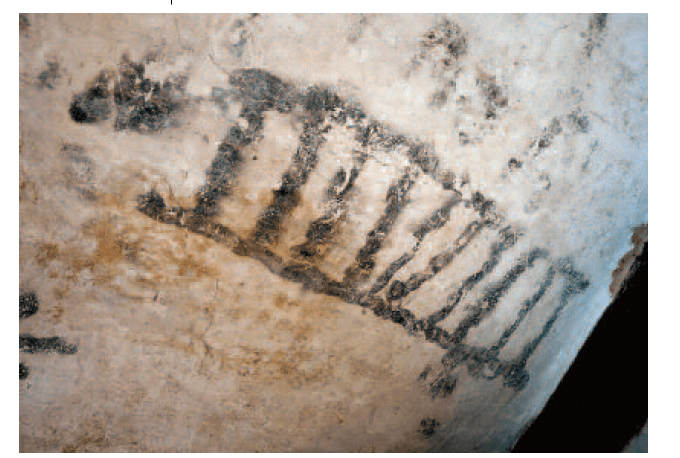

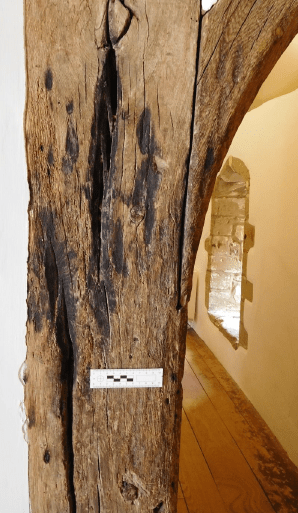

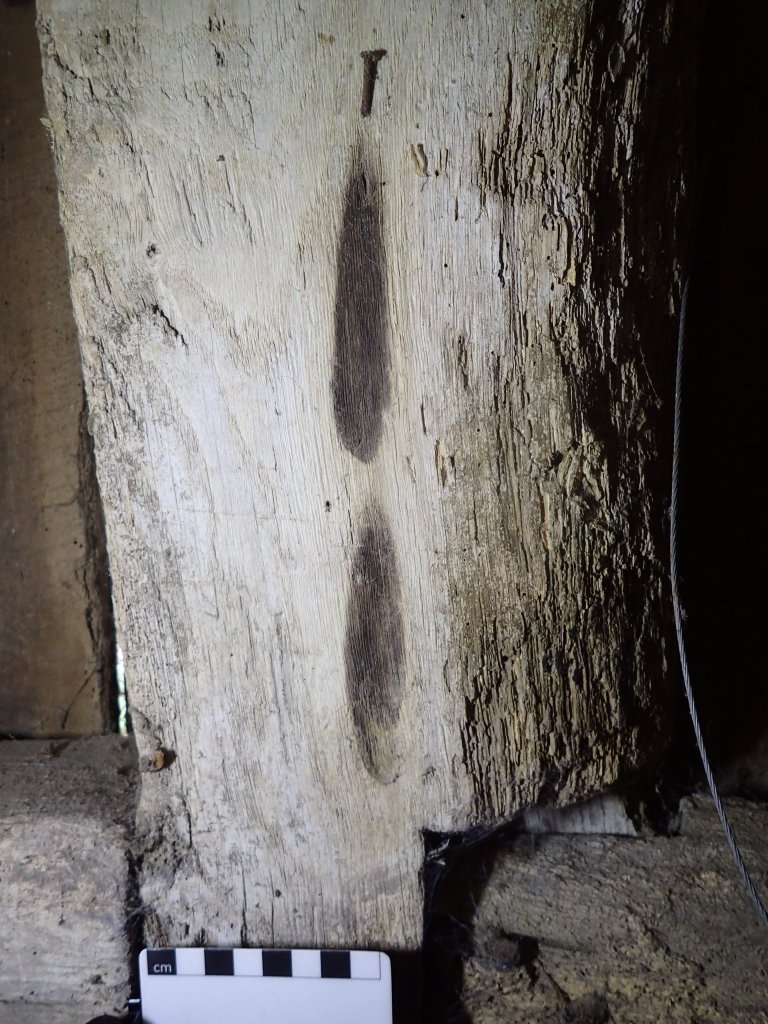

Main image: Multiple deep taper burn marks on the oak door to the nave at St Mary the Virgin & All Saints, Boxley, Kent

APOTROPAICS: THE ROUGH GUIDE #1: TAPER BURN MARKS

For the last 25 years archaeologists have been recording taper burn marks on historic building timbers. These marks are now understood to be the material traces of applied ‘pyro-technology’ – a practice intended to protect buildings and their occupants from harm.

This article is a short history of that research, which highlights the work of a number of researchers from a range of diverse academic disciplines and backgrounds. A new conceptual framework now underpins this revised interpretative paradigm. It is one grounded in a holistic approach which tries to understand the motives which provided the spur to the practice. The agency required must have been based upon shared ideological beliefs. This new understanding is one that has benefitted from having taken a multi-disciplinary approach. It is one supported by the rigour of historical research, the work of folklorists and the material discoveries of archaeologists.

1: Taper Burn Marks: Morphology, defining characteristics.

A taper burn mark can be identified by its ‘teardrop’ shape – not unlike that of a candle flame – being round at the base and narrowing to a point, which is the result of the way the flame was applied to the timber (Billingsley 2021: 48). Its characteristic shape is the result of a ‘controlled’ flame having been deliberately applied to a timber element within a building using a taper. A taper is a long, thin candle that was used for lighting fires, whose design was intended to create a long, steady flame. It is now generally agreed that the taper –rather than a candle or a rush light – was the most likely choice of ‘tool’ to affect the desired result.

Taper burn marks can vary in size, from a few millimetres in length to those of several centimetres and can be found as single burns, pairs or in overlapping multiples. One distinct characteristic of the burn mark is the depth to which the flame has been allowed to burn into the timber, which can be up to several millimetres. They are commonly found on fireplace lintels (bressummers) as well as around thresholds and openings such as timber door frames and windows (Hoggard 2019:94). In other instances they have been found in ‘inaccessible’ locations within a building, such as behind panelling or even under floorboards (Wright 2015:04, Champion 2017a).

2: A Little History of Research

Historically, taper burn marks have been either misidentified or considered to be of no significance at all. Regarded as ‘commonplace’ burn marks on timber buildings, they have often been overlooked or ignored. The presumption has been that the burn marks were the result of accidents due to fallen or badly placed candles (Dean & Hill 2014, Champion 2017b:6). This has now been conclusively debunked.

The Rise of the Heritage Industry

This commonplace attitude to burn marks has changed due to the introduction of modern building surveys undertaken by the heritage industry during the 1990’s and the 2000’s. A reluctance within the heritage industry to excavate or perform ‘intrusive’ operations led to a greater emphasis on non-invasive or ‘remote’ surveys and techniques. Further, stringent rules and protocols were introduced which have regulated the way in which buildings could be restored and/or investigated. There is now an increased emphasis upon detailed recording, promoted within the discipline of ‘buildings archaeology’ to a higher prominence than it had enjoyed before. It is now aided by new 3D scanning equipment which has led to ‘standing buildings’ surveys being undertaken in painstaking detail.

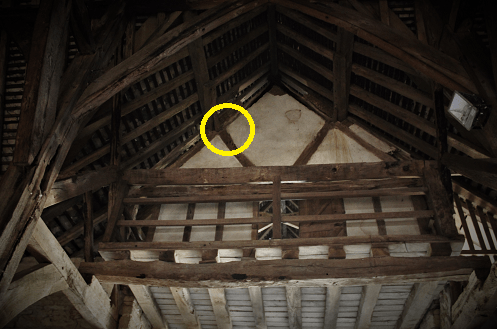

The enhanced recording techniques have become standard protocols for buildings archaeologists. These new techniques soon highlighted far more taper burn marks on internal timber elements than would be ‘reasonable’ when viewed just as casual accidents. The sheer quantity of burn marks recorded in old buildings have made the hypothesis of ‘accidental’ fires untenable (Easton 2012: 46) Further, building surveys that have recorded the official ‘dismantling’ (for the replacement of un-salvageable elements) or ‘renovation’ of old buildings by professionals have brought to light burn marks that had been made in inaccessible locations – such as those that have been found behind panelling, in ‘awkward’ (or restricted) roof spaces and under floorboards (Wright 2015:4, Champion 2017a).

However, the counter-argument for accidental burning persisted, and the phenomenon became the subject of heated debate. Back in the field, archaeological examination of burn marks on timber elements found that, in the majority of cases, ‘where burn marks were found, candle sconces or candle fittings were absent’ (Champion 2017b: 6, Hoggard 2019: 94, Wright 2021). The results from ‘modern’ building surveys culled from the new generation of buildings archaeologists have found burn marks in ever more unusual locations. In churches, they are most often found on the inside of the main door (Champion 2017a), but they have been recorded on Rood Screens, craftsmen’s tools, painted canvases and even on smaller, ‘portable’ objects and furniture (Perkins 2012).

Experimental Archaeology

In 2014, Dean& Hill undertook a programme of experimental archaeology which attempted to replicate both the shape and depth of taper burn marks using a variety of flame types on green oak. This material was chosen as it had been noted that taper burn marks had often been made either at the time of the timber being felled, during the conversion process or not long after construction. Their tests f illustrated that, during the burning process, it would have been necessary to scrape away the layer of carbon and charcoal at regular intervals to create some of the deeper examples. However, in their summary, they noted that although the burn marks sometimes appeared alongside other known ‘apotropaic’ symbols they concluded that there was, ‘no close association between burn marks and other ritual markings’ (Dean & H ill 2014, quoted in Hoggard 2021:95). This conclusion has since been questioned by a number of researchers. Since these early experiments it is now generally agreed the burn marks were often deployed alongside (or in tandem with) other categories of ritual marks (and practices) and as apotropaics in their own right.

In 2021, James Wright returned to the subject of ‘accidental’ burn marks as part of his Triskele Heritage myth-busting series which aimed to replicate and extend Dean & Hill’s experiment. He found that rushlights dipped in sheep fat and hempen wicks resulted in ‘random’ burning. He found that, ‘it was practically impossible to create the classic tear-drop shape.’ A wax taper however, produced the desired results when held at a 45 degree angle to the timber sample. He found that, as predicted, the carbon deposit which appeared on the surface of the wood required regular scraping to acquire the ‘hollow’ profile. In short, he found that it required time, patience and that the making of the marks had all the hallmarks of having been the result of deliberate human intervention (Wright 2021).

3: A DAWNING REALISATION

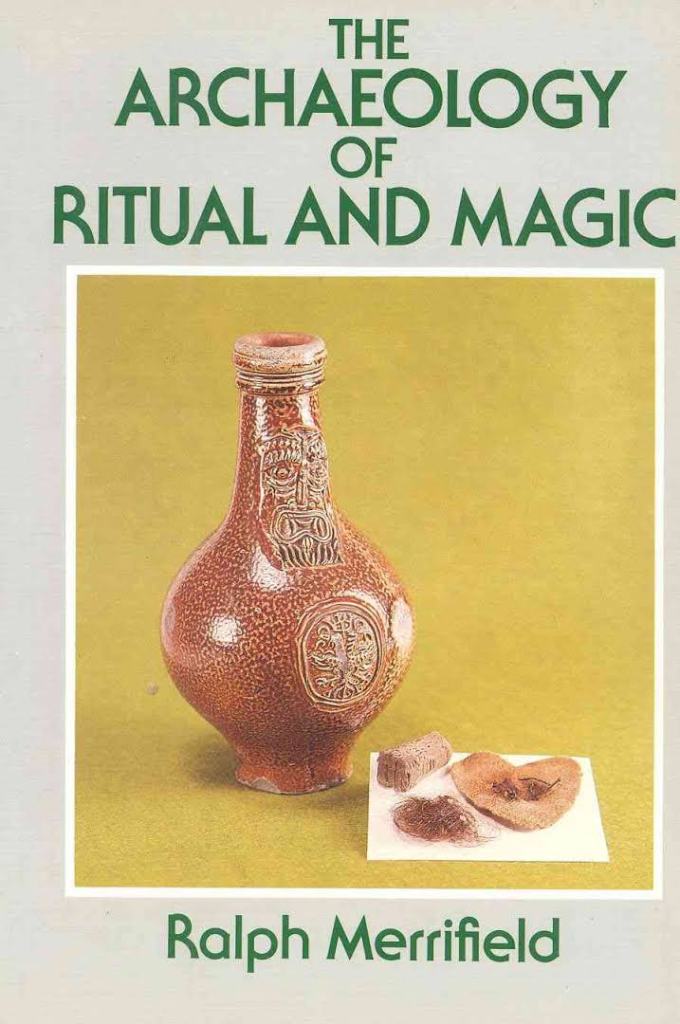

The Archaeology of Ritual & Magic

To understand the current interpretative framework, it is first necessary to place it within its own historical and cultural context. The starting point is Ralph Merrifield’s seminal book, ‘The Archaeology of Ritual & Magic’ published in 1987. The importance of this book to the study area of ‘ritual building protection’ cannot be underestimated. The book was published at a time when both terms ‘ritual’ and ‘magic’ were considered to be almost the sole preserve of anthropologists studying pre-Industrial societies. They were generally considered to be subjects not worthy of serious study within ‘modern’ archaeological fieldwork. Merrifield had been pivotal to the excavations of Londinium, and as part of his work, he became conversant with Roman ‘rituals of commencement’ (foundation sacrifices in buildings) and ‘rituals of termination’ (the ‘closing down’ ritual act of the intentional firing and destruction of buildings and structures) in the archaeological record (Merrifield 1987: 48).

Later, his work in the capital meant that he came into regular contact with buildings from all periods and he began to note ‘unusual’ deposits or artefacts found within the vernacular architecture of the 16th and 17th centuries. He gradually came to the conclusion that buried witch bottles, concealed boots and shoes, mummified cats and hidden charms were not ‘disparate’ phenomena but were, in fact, all elements of what would become known as ‘ritual house protection.’ He believed that the objects had been intentionally inserted into the buildings to act either as all-purpose prophylactics or to act as apotropaics meant to avert the evil eye or maleficium. The occupants may have believed that they functioned simply as ‘good luck’ charms. Convinced as he was, Merrifield still waited until after his retirement to publish the book – such was the negative attitude to the terms ‘magic’ and ‘ritual’ within the archaeological community at the time. Although he had a wide appreciation of most of the categories of ritual house protection, he had only just begun to understand the significance of apotropaic graffiti and seems to have been unaware of the phenomenon of ritual taper burn marks. This was more to do with the fact that buildings archaeology as a discipline was still in its infancy, and built structures had not been placed under the minute scrutiny that they are today.

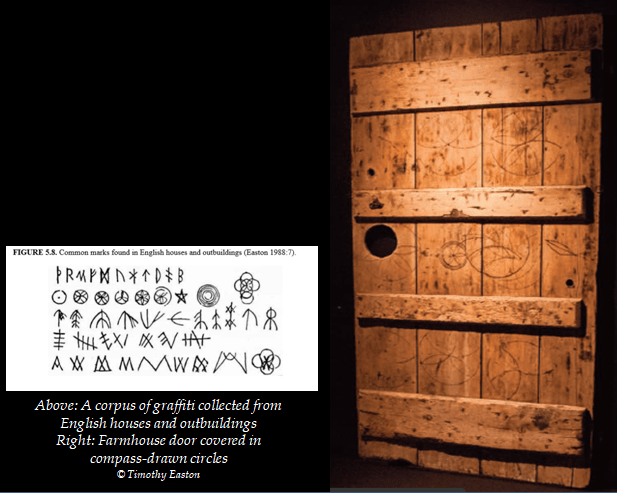

Timothy Easton: Ritual Marks on Timber

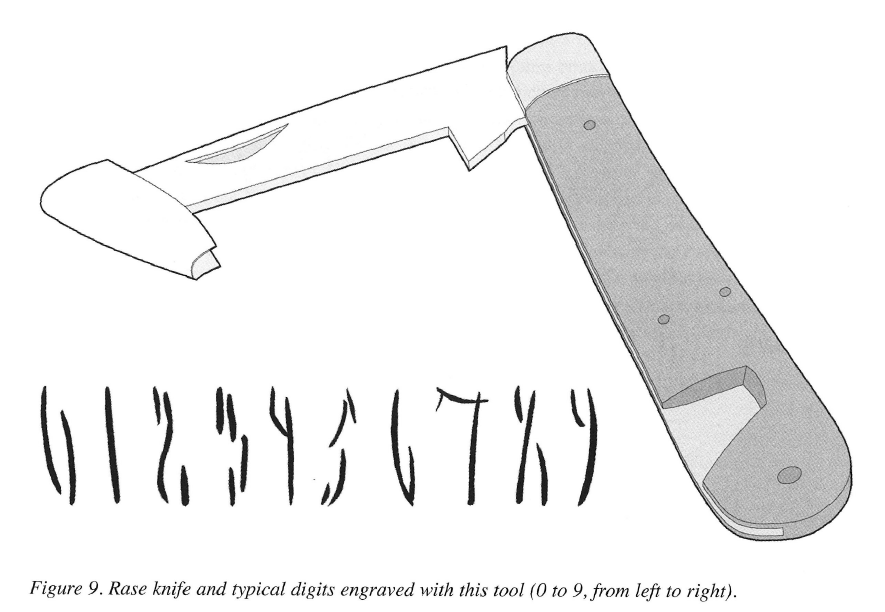

A breakthrough occurred in the late 1990’s, when Timothy Easton, a buildings historian and a student of Merrifield’s, began to notice the repetition of certain symbols carved into the timbers of houses dating to between the 16th and 18th centuries in and around Suffolk. In his article, ‘Ritual Marks on Historic Timber’ (1999) he recorded the symbols on the timber elements which he believed had been made using a carpenters rase-knife; a very specific tool which leaves deeply-cut, prominent marks. The tool was the sort only owned by a craftsman to obtain one would have been beyond the financial reach of most peasants and non-craftsmen.

Marian Marks

The symbols consisted of repeated ‘M’ or ‘W’ symbols (actually formed of two conjoined or over-lapping ‘V’s and known as a Marian Mark), along with compass drawn circles and hexafoils (Easton 1999:22-31). These same symbols appear regularly in the corpora of church graffiti. Easton had seen the extraordinary in the ordinary and made a huge interpretative leap; if the same symbols which had been considered to be masons’ marks exclusive to stone-built churches were also present in the vernacular timber architecture of the 16th-17th centuries, then they could not belong exclusively to Freemasonry or, indeed, to the medium of stone. His work illustrated the link between graffiti and inscriptions found in churches and those identical symbols recorded in secular contexts. He concluded that apotropaic symbols in the context of domestic buildings …’first begin to appear during the early 16th century and remain an almost constant presence right the way through to the 18th…and may survive into the 19th and 20th centuries in rural agricultural buildings’ (Easton 1999 22-24). Easton was able to differentiate between the marks and symbols he had recorded from those pertaining to Baltic Timber Marks or Carpenter’s Marks – which had often been made with a carpenter’s rase knife

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The work of Virginia Lloyd

Merrifield’s diligent work had helped to establish the validity of the archaeological recording of both ‘ritual protection marks’ and the vestiges of ‘ritual practices’ as a genuine sub-discipline of buildings archaeology., In 1997 Virginia Lloyd made one of the earliest identifications of intentional taper burn marks as a real phenomenon that was worthy of proper study alongside other forms of ritual practices. Her pioneering work emerged a result of surveying the buildings of East Anglia. Lloyd was following a lead, having picked up a folkloric reference with regard to the burn marks having once been a ‘common folk practice’ undertaken in timber buildings to counter the danger of devastating fire. Although her article almost went unnoticed, her interpretation was restated in a second paper in 2001 (with co-authors Dean & Westwood as part of the “A Permeability of Boundaries’ BAR report), in which they developed the argument that burn marks should be viewed as the, ‘material evidence for apotropaic practices’ (Lloyd, Dean & Westwood 2001).

4: Candle Powers: Twelfth Night & ‘Sacred’ Candles

Candle Writing

Easton’s article, ‘Candle Powers’ (2011:56) which saw him turning his attention to both the Christian symbolism of the ‘blessed’ candle as a ‘sacred’ object along with its central role within Christian ritual. In the article he highlighted the importance of the blessed candle bringing ‘light’ to the celebration of Twelfth Night. Some of the ideas put forward by Easton – as well as the ritual and symbolic importance of this festival – have been revisited and elaborated upon by Fearn (2017) Hoggard (2019), Champion (2017a) & Wright (2021).

Although not dealing directly with the phenomenon of burn marks themselves, ‘Candle Powers’ outlined his discovery of a collection of symbols and signs that he had been made on the ceiling of a farmhouse. The marks had been made by using the smoke from the tallow wax of a candle – a practice known among cunning folk as ‘candle writing’. The building, located in Woolpit, Suffolk, dated to the 16th century with later additions having been made to the building a century later. The marks had been hidden as they had been subsequently covered over with layers of lime-wash and distemper (Easton 2011: 56).

In an effort to interpret the range of symbols depicted on the ceiling, Easton made a link between the incorporation of several ‘grid iron’ and ‘ladder’ motifs among the symbols marked on the ceiling and the use of the grid iron as a musical instrument during the festival of Twelfth Night. The grid iron, along with an array of ordinary household objects, was sometimes taken up as a ‘rude’ instrument to help make ‘rough music.’ The resulting cacophony was intended to, ‘drive away spirits’ from the home (Easton 2011: 56-57). Subsequently, both of these motifs have been regularly recorded as part of the corpora of graffiti recorded across the secular and religious buildings of England. In these contexts they have been interpreted as visual representations of ‘spirit traps’ – an ‘overt’ type of apotropaic placed to entrap invading evil spirits (Champion 2017b).

Among the more esoteric symbols he managed to isolate the name ‘Sarah,’ which documentary research identified as being the daughter of the Sugate family who occupied the house in the 17th century. He posited that the marks may have been made as a way of trying to cure her sleepwalking – which was often interpreted as possession in the medieval period. It was seen as a ‘disorder of the body and soul,’ episodes of which were believed to place the body in a ‘dangerous and disordered’ state (Easton 2011: 57, Mac Lehose 2013). The marks may have been the material evidence of a ‘specialist’ (such as a cunning man or woman) having made the marks, which may have been done, perhaps, with suitable incantations or prayer (Easton 2011: 56, Gaskill 2018:134). He believed that the archaeological evidence (and the building’s chronology) pointed to it being highly likely that the marks had been made during the second half of the 17th century (Easton 2011: 56).

The Festival of Twelfth Night

’Candle Powers’ consolidated some of the ideas Easton had already been playing with in his 2005 article, ‘Twelfth Night & the Lord of Misrule.’ It was an evening when the world was metaphorically turned ‘upside down’ and the Lord of Misrule reigned, allowing participants to indulge in a brief period of (sanctioned) chaos. In this short piece he had described the late medieval version of the festival which, at the time, was enacted as a ‘solemn’ observance on Christmas Eve and Christmas morning. Unlike todays ‘secular’ festivals, it ended a month’s fasting and ushered in twelve days of feasting, following the appropriate rituals. In medieval Europe, Twelfth Night (or Epiphany Eve) was observed by the singing carols, baking the ‘King’ cake, having one’s house blessed, merrymaking (in the vein of unrestrained cavorting) and the ‘chalking the doors.’ Even by the Tudor and Stuart period people attached great importance to the rituals of Twelfth Night with the aim of, ‘placating unfriendly spirits and protecting the house for the coming year’ (Easton 2005: 26).

Burning issues & The Tradition of the Yule Log

The first article by Easton to directly address the phenomenon of ‘deliberate’ burn marks was, ‘Burning Issues’ (2012), wherein he pulled together a number of disparate folkloric examples from a number of different architectural and archaeological contexts. Although there were regional variations, the winter tradition of the Yule Log generally centred upon the selection of a propitious log to be burnt on the hearth. According to tradition a portion of it was burnt each evening leading up to Twelfth Night (on or around the 5th or 6th of January) and a section of it saved to light next years’ log. The first reference of the custom is from the 17th century. As well as ‘keeping the home fires burning’ symbolically it was meant to illuminate the house and help turn night into day during the winter months. Other traditions state that two large candles were to be bought and lit from the Yule Log once all other lights had been symbolically extinguished. The implication was clear; one of continuity of the hearth and home and a domestic re-enactment of the New Years’ celebration of candles being blessed in church.

Although there are regional variations, the winter tradition of the Yule Log generally centred upon a the selection of a log to be burnt on the hearth; a portion of it was burnt each evening until Twelfth Night (on or around the 5th or 6th of January) and a piece of it saved to light next years’ log. The first generally accepted reference which records the custom is from the 17th century. As well as ‘keeping the home fires burning’ symbolically it was meant to illuminate the house and help turn night into day during the winter months. Other traditions state that two large candles were to be bought and once all the other lights in the house had been extinguished, they would be lit from the Yule Log. The implication is clear; one of continuity of the hearth and home and a domestic reenactment of the New Years’ celebration of candles being blessed in church.

‘Random Misfortune & Malficium

Once this ritual of the passing of the flame had been observed, the remnant of the log was then to be placed beneath the bed for luck. It was thought to be a particularly efficacious totem for the protection of the household against the dangers of lightning and fire. In the medieval world fire, lightning strikes and other apparently ‘random’ occurrences of misfortune were often interpreted as ‘divine’ justice visited by God. Individuals to whom this occurred were considered blameworthy, as the wrath of God was visited only on those who had sinned. The human condition – unable to come to terms with such ‘random’ misfortune – and unable to locate the ‘sin’ that had led to their fate – often sought to blame such caprice on evil spirits or the result of wilful and targeted ‘maleficium’ (malevolent witchcraft). However, even finding a scapegoat was not the end of their misery as, of course, because even though they located the source of their strife they had attracted the attention of witches only as a result of their sin.

In the article, Easton quotes from the poem “Ceremonies for Candlemasse Day, included in the collection, ‘Hesperides,’

Kindle the Christmas brand, and then

Till sunset let it burn,

Which quenched, then lay it up again

Till Christmas next return.

Part must be kept, wherewith to te’end

The Christmas log next year,

And where ’tis safely kept, the fiend

Can do no mischief there.

Robert Herrick (1647)

Having discovered a ‘spiritual midden’ at Hestley Hall, in Suffolk, Easton recorded among the many objects found a number of burnt wooden fragments or cut pieces of timber were present. These included a partially burnt log and half of a small, sawn 18th-century log which had been split into three. The ends had been put to the fire, extinguished and then consigned to the cavity beside an upper fireplace, the implication was that they looked very much like the physical remnants of the ritual of the Yule Log (Easton 2012:45).

Spiritual Middens

Although Ralph Merrifield had recorded numerous examples of ritual acts including the phenomenon of intentionally concealed objects within late medieval buildings, it was Easton who identified and gave name to a new category of apotropaic deposit; the ‘spiritual midden’. Broadly speaking, spiritual middens have now been identified archaeologically as ‘deliberately-curated’ deposits, comprising old worn-out and broken objects – which often included large numbers of patched and repaired items of clothing and shoes. The deposits are characterized as having been intentionally concealed within inaccessible spaces (such as in the voids alongside the chimney breast). In order to do so, the objects had to have been inserted or dropped into place from a difficult-to-access point in the attic above. The clear intention appears to have been to prevent access to the objects and to ‘take them out of circulation.’

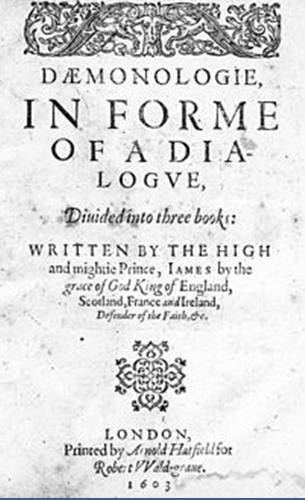

Daemonologie

In the latter part of the article, Easton began to expand upon the themes of witchcraft belief during the Early Modern Period in Europe (c. AD 1550-1800) a time to which many of the timber buildings that he had studied owed their origins. In the main, the 16th to 17th century buildings of the east of England began life as medieval ‘great’ or ‘open’ halls. The rising Yeoman class, keen to display their new-found wealth, had modernised their houses by inserting brick-built fireplaces. Seeing a possible link between the folk beliefs of the period which blamed witches for bad luck and the discovery of ritual protection marks often concentrating upon the chimneys of the period, he turned to some of the literature of the day for further clues.

In 1603, during the first year of his kingship in England, King James I republished his book ‘Daemonologie’ (1597), which he had written as a vehicle to reinforce the ‘truth’ of witchcraft. It was a philosophical dissertation on contemporary necromancy and the historical relationships between the various methods of divination used from ancient ‘black’ magic. The belief among the intelligentsia of the day agreed that witches both existed and could do ill was an adjudged reality. Belief in their existence was embodied in law the Witchcraft Acts of 1542, 1563 and 1604.

Easton highlighted a tract which read,

“ being transformed into the likeness of a little beast or fowl, they will come and pierce through whatsoever house or church, though all ordinary passages be closed, by whatsoever open[ing] the air may enter in at.”

Easton 2011:45.

This passage proven to be so potent that it has been subsequently re-quoted by a number of later researchers including Wright (2015:5, 2021) & Fearn (2017:113). The passage hints at the possibility that the witch’s animal (or spirit) familiar was capable of infiltrating one’s home via the smallest ‘aperture’ or ‘openings.’

The passage is informative as to the mindset of the time and alludes to the feared supernatural dangers of the witch.

‘Spontaneous’ & Devastating Fire Events, Lightning Strikes

Easton’s field work in 2012 included the recording of a taper burn mark on the principal door frame of a Saxon church in Viscri, Transylvania. The mark displayed internal vertical cuts that had been made with a pointed metal object, suggestive of it having been scraped away internally to increase the depth of the mark (Easton 2012:46). A second example from a timber fireplace lintel (bressummer) from Anstruther, Scotland, presented another kind of ‘vertical’ stratigraphy. A number of symbols had been cut into the lintel with a carpenters’ ‘rase’ knife; a specialist carpenter’s tool. The symbols included an ‘M’ (for Maria) and ‘AM’ (for Ave Maria) – what are now understood to be Marian marks. They can appear either in the ‘M’ form or in the overlapping ‘V V’ form (as a ‘W’) which is shorthand for ‘Virgo Virginum’ (Virgin of Virgins). It is believed that in either form the marks were intended to evoke the Virgin Mary. Easton considers the symbol to be one of the most common form of apotropaic, often found in profusion in churches throughout England. After the initial rase knife marks had been added, a number of large taper burn marks had been made after some interval. Some of the taper burn marks had burnt through parts of the original letters. Finally, in a third phase of activity, a minutely cut Marian mark (this time made with a thin, pointed blade) had been added to the hollows of the burn marks, completing a three-fold sequence (Easton 2012:46).

An identical example of burn mark cut through with an ‘M’ was cited from a wall stud at the top of the stairs in an Essex farmhouse. Easton surmised that the depth achieved within the burn marks would have only been possible if there had been a human intervention whereby the charcoal had been systematically scraped away whilst the taper was re-applied. During his ongoing research he found that such burn marks were not exclusive to fireplace mantle beams and that they could also be found located within both ‘cramped’ roof spaces and on the timber frames of windows and doors (Easton 2012: 46-7).

Finally, he concluded that the application of the burn marks could be viewed as a form of ‘inoculation’ whereby the act of applying a flame (under controlled conditions) to the timber had been done in order to guard against the possibility of an ‘uncontrolled’ or random fire. This took the folkloric account collected by Lloyd and applied the laws of ‘sympathetic’ magic to understand the ‘mechanism’ of such acts. In the Middle Ages and through to the Early Modern Period fire could devastate people’s lives. Champion (2017b) agrees, ‘Fire was one of the greatest threats to communities prior to the modern period, most major towns and cities in England suffered at least one major catastrophe.’ Timber buildings, livestock and were all at risk and the danger was ever-present (Easton 2012: 46-47). Equally, lightning and thunderstorms were considered to be the work of supernatural powers in the Middle Ages and churches would ring their bells to dispel the storm and placate uncontrolled forces. (Thomas 1971: 34). Ball lightning was also attributed to higher powers as it left a foul and sulphurous smell in its wake (Easton 2012: 46-47).

On Sunday October 21, 1638 a great storm and lightning strike occurred at Widecombe-in-the-Moor, Devon, which collapsed one of the pinnacles which fell through the roof and the descending fireball entered the nave. An engraving was made of the event 18 years later for a pamphlet which illustrated the event.

Recounted in, Easton (2012: 47).

Case Study #1: Ritual Protection Marks & Witchcraft at Knole, Kent

Between November 2013 and February 2014 buildings archaeologist James Wright undertook a historic buildings fabric survey at Knole, near Sevenoaks, Kent. It included an examination of the joists below the floorboards of 38 rooms as part of a major programme of restoration and repair. A number of apotropaic marks were recorded, having been cut into the floor joists with a rase knife which included grids, meshes, interlocking ‘V’s (possibly Marian Marks) and overlapping ‘X’s (or saltires) (Wright 2015:1).

Historic documentation recorded that a range of works had taken place in 1606 which would have required the integrity of the building to be breached to allow for the insertion of the fireplace and other re-modelling. The works were intended to create a series of ‘royal apartments’ for the visit of the king James I, the author of the above-mentioned ‘Daemonologie.’ As well as writing on the existence of witches, James had also been responsible for taking measures against witchcraft in 1604 when he decreed it to be a capital offence to, ‘summon spirits for the purpose of injuring people’ (Sharpe 2001 quoted in Wright 2015:7). It can be easily surmised that these supernatural threats would have been still fresh in his mind during his stay at Knole and therefore fresh in the minds of his hosts.

As well as the incised symbols, Wright recorded a number of what he termed ‘scorch’ marks which had been made by, ‘directly burning the timber with a candle taper.’ The burn marks were found on a floor joist directly opposite the eastern jamb of the late 17th century fire surround in the King’s Bedroom. He concluded that they may represent the material residue of a form of sympathetic magic, ‘using fire to fight the fires of hell’ (Wright 2015: 5)

Case Study #2: LLancaiach Fawr Manor

In 2017 researchers Brian Hoggard and Alicia Jessup recorded a number of apotropaic symbols at the 16th century manor which included a large number of ritual protection marks including crosses and Marian marks. The first discoveries of note were a dried cat that had been intentionally inserted into a ceiling space, a small ‘spiritual midden’ concealed in the fireplace and a larger midden discovered under the 17th century staircase (Hoggard & Jessup 2017: 1).

The wooden chimney lintel of the fireplace in the servant’s hall possessed an array of deep burn marks. Upstairs, a small attic space which was once the servants’ quarters contained a huge number of burn marks on the main beam and door frame numbering over 100 in total (Hoggard & Jessup 2017: 1-2).

Ritual Death

In an attempt to understand and explain the burn marks he found, Hoggard has ventured a metaphysical hypothesis based upon his own experiences. It ran along the lines of a variation on the historic practice, known as the ‘ritually killing’ or ritual death’ of an object. Such practices are well attested in the prehistoric record; the intentional smashing of ceramics, and the deposition of high-status metal objects into watery locales are a common feature of ‘sacred’ sites. For example, the discovery of intentionally bent swords is now understood to have been an act done with the intention of putting the object out of service in this world and so to ‘transform’ it for use in the next otherworld / underworld. During excavations in London of buildings dating to the 16th-17th century Ralph Merrifield had similarly begun to notice that some deposits contained objects which appeared to have been intentionally broken prior to deposition. This practice is also acknowledged as a component of spiritual midden formation, as all the objects seem to have been patched, soiled and in some instances, intentionally broken.

Hoggard’s suggestion is that the ritual burning of a timber component was undertaken with the same motivation, the intention being to ritually ‘destroy’ the beam. The burn marks were intended to create lights, ‘on a magical or ghostly plane and were meant to have left a ghostly impression of the flame burning brightly on the ‘other side’ (Hoggard 2017:1). This idea was finessed five years later, ‘I strongly suspect that ..the creation of burn marks is, in effect, creating some illumination on a more spiritual or astral plane, shining some light into the darkness’ (Hoggard 2021:95).

Whilst idea has some merit, it is going to be almost impossible to prove ‘intention’ of the agents through normal archaeological techniques. Therefore, a document – similar to those which detailed accounts of the ingredients and intended consequences of the creation of witch bottles – would be required which outlined the belief which motivated the act. So far, such a document has not been forthcoming, but as interest and research in this area has grown, so old documents are being examined anew for clues. Further, Hoggard’s hypothesis suggests that the marks were made with a candle specifically and, so far, direct evidence for any of the burn marks having been made with a candle per se is lacking. The taper allows for more ‘controlled’ burning when held at 45 degrees; candles at this angle would generate a lot of melted wax which would drip onto surrounding surfaces. My experience is that, after closely examining taper burns over the last four years, no significant deposits of melted wax in proximity to the burns marks has ever been detected. However, we may yet happen upon documentation which completely changes our opinion in relation to the ‘true’ intention behind the making of taper burn marks.

Case Study #3: Gainsborough Old Hall

Archaeologist Matthew Champion undertook a survey of Gainsborough Old Hall in 2017 which he described as, ‘one of the best preserved and most beautiful manor houses to survive from the Middle Ages.’ In the Great Hall alone he found burn marks on almost every timber. In the Buttery, the window was ‘surrounded’ by burn marks and at the base of the stairs he found, ‘literally dozens of burn marks’ (Champion 2017b:5).

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Case Study #4: Donnington –le-Heath, Leicestershire.

In 2016 Alison Fearn made an examination of the assemblage of burn marks – along with other graffiti and symbols – which had been made onto the building fabric at Donnington-le-Heath Manor, Leicestershire. Most notable was the sheer quantity of taper burn marks in a distinctive ‘hollow-bowl’ shape. There existed clear spatial patterning with the greater concentration of marks on the first floor; focusing on or around doorways leading to the west wing and on the timber frame that divided public spaces from ‘private’ ones. Finally, the interrogation of the data highlighted a greater concentration in proximity to the bedchambers. Based upon these results, Fearn has forwarded the case for the burning to be a ‘gendered activity’ when considering the historic role of the female within the household and their access to the various locations within the building. Her research has added an interesting new line of enquirey to the current research agenda (Fearn 2017: 92-102).

As part of the discussion, Fearn returned to Easton’s idea that the rituals of Twelfth Night might hold a clue to some of the ritual activity. Whilst perusing Thomas Kirchmaier’s, ‘Christmas of Old in Germany’ she noted the passage which seemed to at least allude to applying taper burns:

‘Another takes the loaf, whom all the rest do follow here,

And round about the house they go, with torch or taper clear,

That neither bread nor meat do want; nor witch with dreadful charm

Have power to hurt their children, or to do their cattle harm’

From the German of Thomas Kirchmaier (1553 quoted in Fearn 2017: 94).

Case Study #5: Ightham Mote, Sevenoaks, Kent

In 2019 I undertook a non-invasive photographic survey of the 14th century Ightham Mote moated manor house using English Heritage Grade II protocols. The survey recorded a number of compass drawn circles, Marian marks, saltires and other ritual protection marks both in the Great Hall and around the 17th century stone fireplaces on the first floor.

As well as a variety of symbols having been made on the exposed stonework, twenty-nine deliberately applied taper burn marks were recorded on the building fabric (and in one instance on a chair) at Ightham Mote. Many were recorded on the timber Rood Screen in the New Chapel but other examples came from the doors, timber studs and the newel post of the spiral stairs in the gatehouse tower (Perkins 2019).

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Matthew Champion: Fighting Fire With Fire

In a 2017 blog, Matthew Champion cited a number of examples of burn marks found within a wide variety of buildings dating from the late medieval to the Early Modern Periods. Echoing Easton’s earlier ideas outlined in ‘Candle Powers’ he set out a persuasive argument for the use of candles – specifically those having been made from beeswax and blessed– in both Christian ceremony and how their application had been ‘interpreted’ within various folk traditions (Champion 2017).

Candlemas

The festival of Candlemas is a Feast Day which is known variously as the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, the Purification of the Virgin or the Feast of the Holy Encounter. It was traditionally held in early February, forty days after Christmas. Like the observance of Twelfth Night, it was preceded by a period of fasting. It was celebrated by way of service and prayers followed by a procession around the churchyard. The solemn procession is meant to represent the entry of Christ (‘who is the light of the world’) into the Temple at Jerusalem (NA 2021). Traditionally, the congregation would bring candles to the church so that they could be blessed; the candles could then be taken home for use for the rest of the year. Candles which have been blessed by a Priest are deemed ‘particularly powerful’ as they were considered to be capable of driving away the Devil and so therefore protect the home (Champion 2017b: 10).

There Is A Light That Never Goes Out: The Paschal Candle

Rituals surrounded the Paschal Candle, as it role was to represent the Resurrected Christ. Both the candle and the precious nature of the melted beeswax were venerated. Similar to the tradition of the Yule Log, much play was made of the fact that, during a special ceremony, all lights would be extinguished as the congregation gathered in the church when new candles were lit from the Paschal Candle. Tapers lit from the Paschal Candle were regarded as, ‘a particularly potent charm for the protection of children and mothers to be’ (Champion 2017b: 10), underlining both the feminine aspect of the ritual and its relation to childbirth.

The Qualities of Wax

The practice of burning candles specially fabricated to the height of an individual was another curious variation; Champion cites a document which recorded that, ‘in 1285 King Edward I made an offering of wax at St Mary’s Chatham of, ‘a total length equal to the combined heights of the Royal Family.’ In a perverse reversal of such beliefs, the candle (or wax) could likewise be used in malicious witchcraft whereby a candle could be ‘identified’ or modelled as a representation of the victim. So as the candle burnt, so the victim would ‘waste away’ (Champion 2017b:11-13).

There was also a trade in the wax itself; it was systematically recovered from shrines and remodelled into new candles or fashioned into ex-voto objects to complete the cycle of deposition at shrines. Ex-voto objects often took the form of a body part for which the pilgrim sought healing, leading to the creation of small models of feet, hands limbs and hearts to leave at shrines (Champion 2017b: 10-11).

Funerary Candles

Champion has highlighted the central role candles played in funerals and funerary ritual and quotes an example from Ireland where five candles were requested to be placed around the body of the departed to, ‘protect against evil spirits and the Devil.’ Their continued use as being central and crucial to funerary ritual survived the Reformation.

‘When a death takes place candles should be burnt in every apartment of the house during the whole of the night until it (the body) is buried’

1888 Folklore 263

‘On the Scottish lowlands… the body should be washed and laid out and the oldest women should light a candle and wave it three times around a corpse. The candles for saining (blessing) should be procured from a wizard or witch or a person with flat feet..for all these people are ‘unlucky’..the candle must be kept burning through the night’

c.1816 Wilkie MS (Henderson Northern Counties 1866 36-7

Both of the above cited in, Opie & Tatum (1989:53-56).

Champion gave several examples of high-status individuals leaving requests to be enacted on their death. This often included the financial provision for the lighting of candles to be placed around their body as it lay in state. In some ways these could be considered posthumous apotropaics, enacted after death and designed to aid the soul through Purgatory. In the early medieval church, it became the norm for the elite members of society to make such requests in their wills and build chantry chapels within which their requests could be enacted. A typical church scene of the period would include candles being burnt in side chapels or chantries, especially during the principal feasts of the church (Champion 2017b: 11).

Spontaneous & Accidental Fires & Lightning Strikes

The fear of fire continued to be a very real threat right up to the 19th and 20th centuries. In former times, and unable to come to terms with misfortune, some inhabitants suspected that the fires were the result of supernatural acts, most specifically malevolent acts of witchcraft.

The 16th century woodcut, ‘Hort an new schrecklich abenthewr Von den unholden ungehewr‘, depicts a burning house surrounded by parading witches; elsewhere, ‘cancelled out’ Marian marks on the fireplace lintel appear permit witches to enter a chimney. Champion concluded that burn marks may also possess a direct apotropaic function as they, ‘both denied witches entry to the building via the portal onto which the marks were scorched and at the same time inoculated the timbers from further burning’ (Champion 2017b:13).

British Museum. Accession No.1880,0710.582

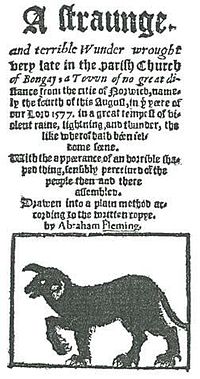

The Legend of Black Shuck

Not only witches were blamed for lightning strikes, there also existed a folk belief in black dogs – who in doing the Devil’s bidding – could wreak havoc as recorded in the legend of the ‘devil dog’ Black Shuck (Champion 2017b:13). In Blythburgh,

“On 4th August while the minister was reading the second lesson a strange a terrible tempest ‘strake’ down through the wall of the church, toppled the spire down through the roof so that it shattered the font, tumbled the bells and the jack of the clock (he was repaired and it still there), killed a man and a boy and scorched many members of the congregation. It was known that this visitation was of the Devil, because as he fled out of the north door on his way to Bungay his fingermarks were revealed, and the truth of the legend verified“

“The bronze plate at the Butter Cross records the event also occurring at Bungay on the same day and in the same storm as at Blythburgh. On Sunday August 1577, when Old Shuck or Black Shuck the terrible black dog of East Anglia, appeared in the church during a thunderstorm (the same one in which the Devil left his mark in Blythburgh church) and wrought great havoc.”

(Seymour 1970 :43-44,138).

and terrible Wunder wrought

very late in the parish Church

of Bongay, a town of no great distance from the citie of Norwich, namely the fourth of this August, in the yeere of

our Lord 1577, in a great tempest of violent raine, lightening, and thunder, the

like whereof hath been seldom seene.

With the appearance of an horrible shaped thing, sensibly perceived of the

people then and there

assembled.

Drawen into plain method according to the written copye.

by Abraham Fleming. British Library Manuscript C27.

The story of Black Shuck a classic case of an ‘illusory correlation’ – often encountered in folkloric accounts – whereby unexplained phenomena (in this case ritual burn marks) has become the subject of a fanciful local legend after the event. We now know of course that the marks were made deliberately made by human hands – even though it may have been driven by the fear of lightning strikes!

Case Study #6: St Mary West Malling Kent

During a preliminary survey at St Mary’s church, West Malling, I found that both the Nave and Chancel of the church were almost devoid of graffiti, save for a Latin cross on a window mullion and several other ‘ephemeral’ marks. The main evidence of ritual protection of the building was discovered in the tower crossing below the bell chamber. The first clue was a lightly cut compass – drawn circle on the outer face of the crossing door. Inside, the stairwell to the tower had been panelled with a series of wooden planks upon which a number of scratched motifs had been cut. The symbols included a large ‘mesh’ (or grid) motif, accompanied by a compass-drawn design, several saltires (composed of X’s – a known ‘occlusive’ or ‘barrier’ symbol) and numerous deep taper burns applied to the woodwork as different ‘layers of protection’ (Perkins 2020).

Alas, it would appear that these apotropaic precautions were not enough to prevent the tower being struck by lightning in the early 18th century,

“There happened a great tempest of thunder and lightening and sett a fire the spire of the church, (which) broke down through the roof and ceiling of the body of the church and through the belfry door, broke down the pendulum of the clock, melted the bottom of the pendulum, went through the head of the chancel, and did a great deal of other damage, especially to the spire, on Monday morning about 6 o’clock, the 17th day of November, 1712”

(Quoted in Tatton-Brown 1995)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Bless This House

Folklorist John Billingsley touched upon the subject of burn marks in his book ‘Charming Calderdale’ in 2020. Having followed the arguments, when it came to writing his own book he concurred that the process of creating burn marks was a, ‘deliberate and time-consuming act which fits the criteria that would allow for a spell or prayer to be spoken.’ Acknowledging the lacuna in the documentary evidence he pointed out that, as researchers and archaeologists, it is up to us to infer a meaning from what the act implies (Billingsley 2020: 48-49).

Taper burn marks are, therefore, a ‘willed’ magical act based upon folk custom communicated through oral transmission and copied by rote. Unlike other ritual practices such as hidden or concealed objects whose efficacy is based upon secrecy, the taper burn mark is often located on clearly visible locations for ‘overt’ display (Billingsley 2020: 48-49).

5: WHO MADE THE MARKS?

The Clergy

When it comes to the past application of apotropaic symbols within the built environment, it is clear that some, at least, would have required ‘specialist’ equipment. It is possible that some mark making may have been accompanied by chants and spells. Some may have required only the ability to replicate a recognised folk tradition that had been learnt by rote or one that had been practiced (and therefore copied) generationally. In most instances, it has become clear that many of the practices were transmitted orally as they would have been considered ‘common place’ actions that did not require explanation. Historical documentation relating to many of the practices is so far lacking.

It has been queried as to whether any of these practices were enacted by the local priest or clergy. The consensus broadly seems to be that this is unlikely, as the local priest would have had recourse to his own spiritual ‘arsenal’ of tried and tested ‘official’ liturgical formulae (such as exorcism for buildings in extreme cases). Furthermore, it is possible that some such acts of ritual protection could have been perceived to be mildly heretical. That is not to say that the Clergy did not have knowledge of the use of folk practices within their communities, but rather they simply turned a blind eye to the practitioners and placed some distance between themselves and the undertaking.

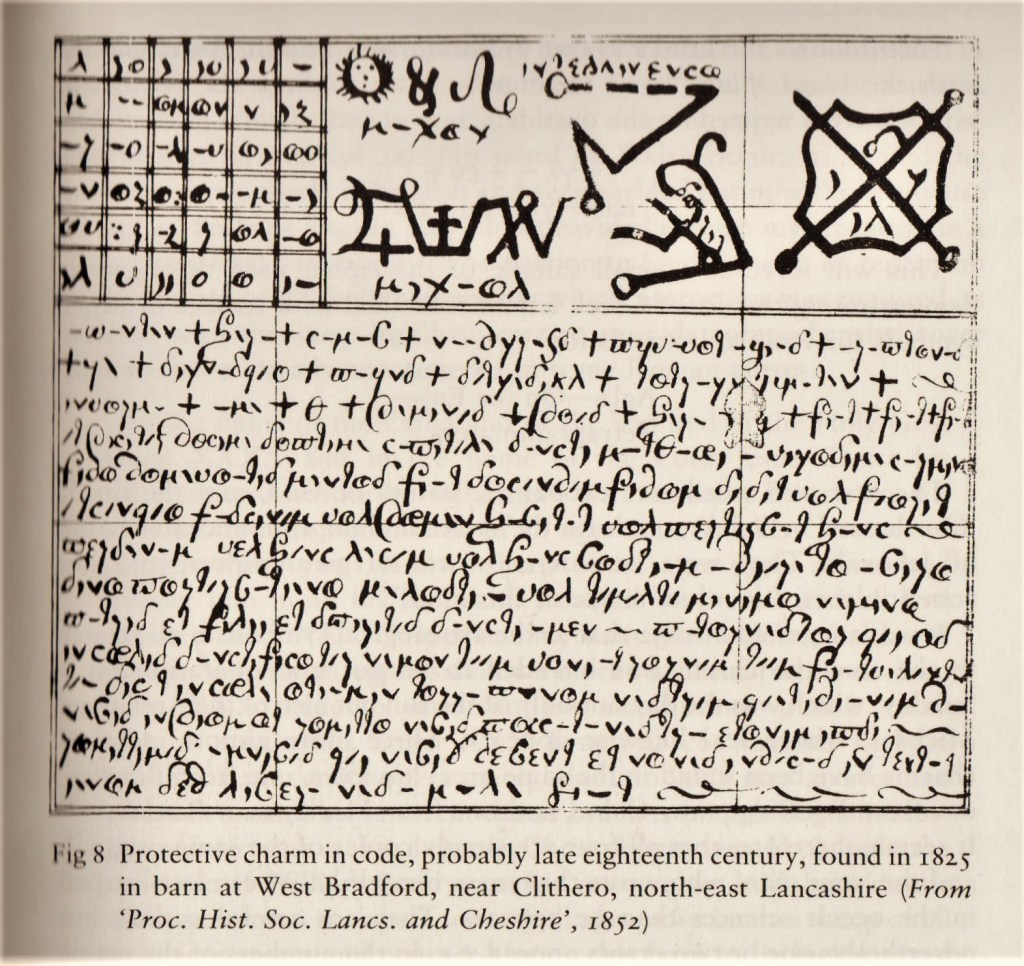

Cunning Men & Women

Back at the beginning of this article we looked at Easton’s ‘Candle Powers’ (2011) and the case of the smoke writing that had been found on the first floor ceiling at Woolpit, Suffolk. The writing and symbols were of a completely different order to the phenomenon of taper burn marks but they may still have shared a number of characteristics in their execution.

One of the main tenets of his interpretation was the inclusion of those symbols which related to astrological divination and the inclusion of fragmentary Greek and Latin peppered with Christian motifs – in other words, those symbols used in ‘white’ magic. To Easton, these drew to mind the kind of written charms illustrated in Merrifield’s book, such as one found in a barn in West Bradford, Lancashire and one recovered from a cowshed in Pentrenant Farm, Powys. (1987:149-153).

It was clear to Merrifield that the charms had been fabricated by a local cunning man (or wise woman) who had used a combination of symbols including Greek and Latin letters (often learnt and copied out by rote), magical word squares, astrological ciphers and ‘occult’ symbols, written out side-by-side with short Christian tracts and other ‘disparate’ symbols known to be associated with deflecting the evil eye. ‘The charms were an admix of prayer and spells, piety and ritual enchantment, invocations of various deities and corrupted Latin. It was a kind of white magic that lay on the borderland between religion and sorcery’ (Merrifield 149-153). In ‘Candle Powers’ Easton had asserted that the motifs used in the candle writing appeared to reveal a ‘shared knowledge’ of symbols that may have been considered efficacious in offering protection against the cultural anxieties surrounding the potential ills caused by evil spirits or malicious witchcraft.

Craftsmen & Tradesmen

In Burning Issues (2012), Easton clearly identified the suspects; ‘many of …(the burn marks) must have been made by the carpenters at the time of construction’ (Easton 2012:46-47).

A similar conclusion was drawn by Wright at Knole House where he believed that the apotropaic symbols – in common with the carpenter’s marks – were carved using a rase knife. It was also evident that the taper burn marks that appeared to be ‘horizontal’ on the timber elements were in fact the result of having been made on vertical timbers in the framing yard before they were laid horizontally. The orientation of the marks implicated the carpenter’s intervention at an early stage of construction. Wright concluded, ‘it is possible… that the marks in the King’s store…were added by the carpenter’s in a planned system prior to construction on site…under the direction of the foreman Matthew Banks’ (Wright 2015:2,5,8).

Matthew Champion has applied minute archaeological examination of the burn marks to provide solutions for dating. It supports the view that (at least in some cases) burn marks had been applied to the timber, ‘prior to their incorporation into the structure’ whilst other burn marks had been subsequently truncated when timbers had been re-cut or re-fitted. Close examination of other burn marks revealed that their shape had become ‘distorted’ through the opening up of seasoning cracks in the grain of the wood. It suggested that they were made onto the timber, ‘just after it had been felled or a short time afterwards’ which again implicates the craftsmen as, ‘the marks applied during the construction phase…may have been put there by the builders to inoculate the house against fire’ (Champion 207:15).

Builders and carpenters – those present at the beginning of a house’s construction -are also thought to be responsible for the practice of concealing objects within the building’s fabric according to Hoggard (2019:8), actions that were ‘not unlike installing a (modern day) burglar alarm.’ Old customs would have been popularly understood at the time of their making and existed without record or explanation (Billingsley 2020:48). However, the more ‘exotic’ apotropaics – such as the creation of mummified cats and ingredients required for witch bottles- would almost certainly have required the intervention of a cunning man or woman.

In his review of the Calder Valley, Billingsley (2020:16) concurred that the builders were likely to have been culpable for burn marks, graffiti or concealed objects ending up within the fabric of the building; ‘…vernacular architecture of this period was created when builders still saw their responsibility as lying not just in construction but also in looking after the welfare of those who were to inhabit the buildings…it is likely that builders would have employed techniques they considered customary.’ Objects may have been placed without the patron’s knowledge (the concealed) as opposed to ‘visible’ apotropaics such as graffiti (the revealed) which may have been added in line with the patron’s wishes (Billingsley 2020:16).

6: WHY APOTROPAICS?

It is now generally agreed that, where taper burn marks have been recorded on timber elements within the vernacular and ecclesiastical buildings of both pre and post Reformation England – they are the result of intentional ritual practice. The marks can be understood as the material vestiges of an act of sympathetic magic which was a result of our ancestors’ ‘cultural anxieties.’ Contextually, they are temporally and culturally specific. They belie the human impulse to allay the fears held by an individual (or family) using an apotropaic ‘technology’ as an insurance against future misfortune. Whether the motivation was driven by a pragmatic concern with the threat of fire (either ‘spontaneous or lightning driven) or fear of ranked malign forces of supernatural origin, is debatable. Both would have qualified as perfectly reasonable precautions in a pre-Enlightenment world. Whatever the motive, either scenario would have had the potential to lead to the downfall of and ruin an individual or family and/or a loss of livelihood and home.

In the late 20th century, it was the archaeological discovery of ‘exotic’ deposits and ‘unusual’ objects within late medieval buildings that led Ralph Merrifield to develop his theory of a ‘coherent’ (if eclectic) practice of ‘ritual building protection’ having existed in the past. It was the nature of those deposits – which seemed to have parallels with those known from past societies and cultural groups (such as Roman ritual practices associated with buildings) – which lead him to believe that many of the ritual acts had been motivated by the fear of supernatural forces in a pre-Enlightenment age. Many seemed to have had ancient antecedents in rural folkloric practice which had then been carried into urban contexts and symbols only previously seen in churches into secular buildings, ‘the existence of a custom is revealed only by repetition (of) common patterns of ritual activity’ (Merrifield 1987: 189).

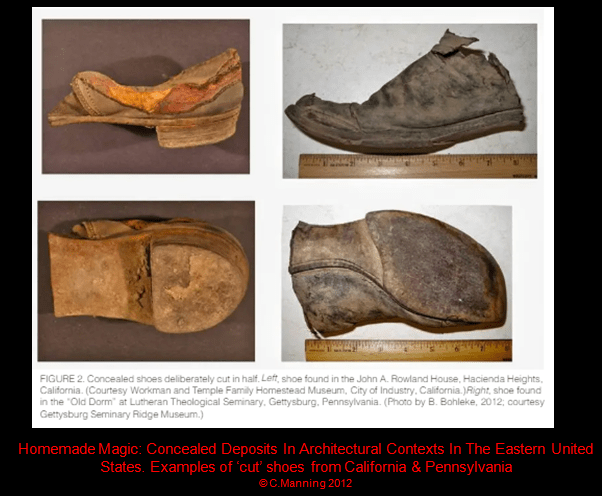

Merrifield had noticed that many of these deposits in post-medieval buildings were located close to, or marked upon, the threshold structures themselves. He believed that some of the objects may have acted as ‘decoys’ whos eintention was to divert any evil that might try and enter the house. ‘Those responsible (for the placing of deposits or objects) ..felt that by so doing so they were somehow giving spiritual as well as physical strength to the building’ (Merrifield 1987: 106, 120-21). He was one of the first to note the vulnerability of a building’s fabric by the addition of a chimney which, ‘might give ready access to spirits.’ Dried (or mummified) cats found in wall voids against, ‘the real fear,, (being) …spiritual vermin rather than rodents..as the great fear of familiar spirits..(which) often took the form of rats or mice.’ Old and worn shoes found concealed in voids around the house were, ‘evidence for the householder believing that they held some ‘virtue’ and (were believed to have) emanated general prophylactic qualities.’ (Merrifield 1987: 128, 131, 136).

Finally, he highlighted the historical records of witchcraft accusations and persecutions of the early modern period, ‘ the fear of witchcraft…towards the end of the Middle Ages became a mania for complex historical and psychological reasons’ (Merrifield 1987: 159). As evidence, he noted the exhortations against witchcraft by Pope Innocent III, Luther & Calvin, the works of Sprenger & Kramer, ‘Malleus Malficicarum’ (1486) James I, ‘Daemonologie’ (1597), Jospeh Granvil ‘Sadducismus Triumphatus’ (1681) among others, ’the authors were much concerned with the counter-measures taken against witchcraft.’ In exhaustive detail he then went on to discuss the folk practices undertaken by the peasantry, which included the application of horseshoes (or iron objects) to thresholds, hag stones and churn spells in barns and farm buildings…all possibly climaxing with perhaps the most iconic of all counter-witchcraft object of all – the witch bottle – preserve of the cunning man or woman (Merrifield 1987: 162, 163-175).

Fearn (2017) confirmed that the marks found at Donnington-le-Heath were likely to be ‘ritual’ in nature and that the majority had an apotropaic function designed to ward off evil influences and misfortune. The symbols had had the intention of, ‘adding a ‘significant layer of protection to ‘vulnerable’ areas of the structure.’ She revisited the idea of taper burn marks being a form of protective inoculation against fire and lightning but added that the burn marks were far more likely to reflect a, ‘more complex belief system’ rather than regarding them simply as protection against fire and lightning, which seemed to her to be , ‘overly simplistic’ (2017: 92, 1113). Far more interesting is her suggestion that the action of making taper burn marks could have been a gendered activity; giving birth, attending the dead, housekeeping and domestic animal husbandry would have all fallen to the woman’s role in the house. Therefore, e making the marks may have been the female preserve of the household, enacting a kind of ‘domestic religiosity’ (Fearn 2017: 92, 113-117).

In 2017, Champion ran through many of Easton’s original hypotheses whilst elaborating upon them and opening out the discussion. For him, it was the ‘object’ which facilitated the burn mark – the candle – as opposed to the marks themselves – which were considered to be the most important component that led to their interpretation (Champion 2017b:10). He reviewed the evidence relating to the celebration of Candlemas as the blessed candles taken back to the domicile would have had the power drive away the Devil and protect your home, ‘candles….were associated with protecting children, infants and mother-to-be. The use of candles in funerary contexts appear to be just as important as they, ‘put all the powers of darkness to flight’ and in Ireland, the five candles around the body were, ‘protection against evil spirits and the Devil.’ Similarly the Twelfth Night celebrations were aimed at ,‘driving away of demons and spirits..and, in the marking of crosses on ceilings, witches.’

As well as the importance of wax (as a sacred substance in of itself) he also noted that the danger of it falling into the wrong hands for perverse use by witches. The corruption of a once ‘holy’ substance being used for making diabolical images was, ‘…(an) act of malficium (which) was often an inversion of recognised beneficial charms and beliefs.’

Likewise, the threats of fire and lightning (of the kind generated through witchcraft) led to physical measures which were, ‘sometimes taken to counteract such apparent evils’ which would have included the use of ‘sympathetic’ magic. Lightning – and ball lightning specifically – was blamed on the devil or possessing a supernatural origin. He concluded by asking whether ritual taper burn marks had been made in an attempt to drive away evil spirits,…keep witches at bay or to protect the building from fire and lightning but concluded that, it was likely that all three may have been the case’ (Champion 2017b:10,11, 13).

Wright (2021) has had seven years of practical experience as a building archaeologist, recording burn marks in situ within a number of different architectural milieus. Reviewing the evidence for a second time, has concluded that there, ‘may be the physical manifestation of anxieties about the presence of evil or bad luck linked to the acknowledged protective powers of candles against evil spirits’ (Wright 2021).

7. When were they made?

Dating taper burn marks is problematic for lots of reasons. As Matthew Champion has succinctly put it,’(they) could have been applied at just about any point between the construction of the building and the moment of discovery (2017: 7). In the first instance, the chronology of the building, along with a detailed inventory of all the repairs, additions and restoration work undertaken during its lifetime will provide a solid foundation upon which to study of the burn marks themselves. In some cases, taper burn marks have been painted or plastered over or simply covered by later structural additions or panelling. Once the chronology has been established to provide a framework, targeted dendrochronolgy can be utilised to date the felling dates of separate timber elements. As oak was expensive and a precious resource both recycling and re-use of old timbers was common. Dendrochronology works by taking ‘cores’ from (in the first instance) the internal, structural timbers of the house and measuring the annual growth increments (rings) of a tree to provide a felling date. The number, width and pattern of the rings from certain tree species can provide the age of a piece of wood as well as provide information on the climatic conditions during the tree’s growth (Chrono 2022). This way, a range of dates for the felling of a tree can be generated.

Once the timber had been felled, the conversion process was begun, where trees were transformed from basic trunks into beams (or other structural elements). In the pre-mechanised period the timber would have been converted by axe or adze before it was sawn to the desired shape (Harris 2000:17). From the time the tree had been felled to the time that the house frame had been constructed, the timber would have begun to warp and settle as the wood seasoned and slowly dried out. Some buildings were further affected by their surrounding conditions (micro-environments), so therefore ‘movement’ within a timber house was moisture dependent.

With this in mind, the third method which facilitates dating is the close examination of the burn mark itself; as the green oak dried out seasoning cracks would have opened up along the grain of the wood. If a taper burn is applied to the fresh (green) wood, its shape will become ‘distorted’ over time as the cracks open up – further, there will be no evidence for burning inside the cracks as the mark was made prior to seasoning. Burn marks made over pre-existing cracks will not have been subject to the same kind of distortion and burning will be discerned within the cracks themselves. Even taken together, the above methods will only provide an estimate for when the burn marks were made.

An important development in this regard was the survey of taper burn marks recorded at Donnington-le-Heath Manor by Alison Fearn in 2017, as she was able to tie-in the application of the burn marks to the dendrochronology dates taken from the timber elements. Dendrochronological analysis had been applied systematically within the manor and it was found that the interior woodwork consisted of a mix of 13th and 17th century timbers. The range of dates was accounted for by later structural additions, repairs and renovation. The roof trusses that support the main roof had been dated by dendrochronology to circa AD 1618 whereas the internal door jambs to the arched oak doorways of the upper floor wings are dated to between AD 1272 and 1307 (Fearn 2017:99). During the survey, she recorded a number of taper burn marks that had become distorted as seasoning cracks had subsequently opened up, indicating that the scorching had occurred on green timber either during the conversion process or shortly after completion of the building (Fearn 2017:102,106) Her work provides us with one of the earliest examples of taper burn marks on structural timber and establishes the fact that the practice was already being undertaken in the pre-Reformation era (Fearn 2017:102,106).

Wright (2015:1) had also saw the implication of carpenters having made the burn marks on timbers used at Knole House during the re-modeling of 1605-8, thus providing a post-Reformation example. One valuable outcome is that it has now been archaeologically proven that, whilst taper burn marks were sometimes made at the beginning of the construction process, many were added later. It has now been demonstrated that the phenomenon spans the medieval to Early Modern periods (Wright 2021). This at last dispels the formerly held view that the marks were confined to post Reformation England (Champion 2017b: 7).

However, we have to ask the question as to whether the practice was undertaken over the centuries as an unbroken continuum over the centuries or whether the intention or motivation for making the marks changed over time? We have seen elsewhere that the desired outcomes of both concealing shoes and the burying of witch bottles subtly altered between their original use (and intention) in the 16th/17th centuries and the final dying out of the traditions in the late 19th/early 20th centuries (Perkins 2021). Could something similar have happened with the practice of applying taper burn marks? Unlike concealed shoes and witch bottles it appears to be harder to see – at least archaeologically – the ‘difference’ between the application of pre and post Reformation burn marks. Perhaps hitherto unnoticed nuances will only become clear through even more finessed spatial patterning techniques and minute examination.

8: HOW WERE ‘TAPER BURN MARKS’ PERCEIVED TO WORK?

Reviewing the evidence, it is clear that the practice of applying taper burn marks to the timber elements of buildings were made during two distinctly different periods underpinned by two very different belief systems. The medieval period was characterised by the dominance of Catholic ‘magic’ (a belief in the power of Saints, relics and of miracles). The latter era – the Early Modern Period in Europe – although often associated with the emergence of scientific thought, was in fact still functioning in a pre-‘mechanistic’ pre-Enlightenment world. That is not to say that it lacked intellectual ferment, as several intellectual belief systems were jostling for supremacy. Variations on Hermeticism, Rosicrucianism, Paracelsianism and Neo-Platonism were all being practiced at the same time as pseudo-sciences.

From the 15th century onwards, Neo-Platonism had flourished during the Western Renaissance. Neo-Platonism was a major influence upon Christian theology throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages in the west (SL 2022). Neo-Platonic theory understood the world as a ‘pulsating mass of vital influences and invisible spirits’ (Thomas 1971: 266). The Universe was believed to be peopled by a hierarchy of spirits which manifested occult influences and sympathies. The cosmos was understood to be an organic unity of which every part bore a sympathetic relationship to the rest (Thomas 1971: 265). During this period, three main types of magic were being practiced –

Natural magic – which exploited the occult properties of the elemental world.

Celestial magic – which involved the influence of the stars (astrology was believed to have a scientific basis).

Ceremonial magic – which appealed to spiritual beings or entities (rituals of this type proliferated during the Renaissance)

During this period, magic was being practised not as a medieval survival but was enacted as a Renaissance re-discovery of the Classical tradition. In the intellectual climate of the day, magical activities gained plausibility and the ‘Doctrine of Correspondences’ was believed to exist between each part of the physical world (Thomas 1971: 265, 326). It was believed that networks of sympathies, analogies and correspondences linked everything in the cosmos together and enabled other than purely ‘mechanical’ means of manipulating the world. They believed that a variety of ‘things’ – from artefacts to landscape elements – posessed special properties such as agency, consciousness and personality (Herva & Yilmaunu 2009: 234). People’s lives unfolded in relation to a richer ‘enchanted reality’ where the material and the spiritual were inexplicably intertwined. Spirituality was about recognising the richness of the rationally-constituted world and people’s deeply reciprocal relationships with that world (Herva 2012:76-7, 83).

The Weapon Salve or Powder of Sympathy

In the 17th century, the Paracelsian movement saw nature working through the laws of sympathy and antipathy – of imitation and correspondence – which we understand today as sympathetic magic. One of the most famous examples of this application was the ‘Weapon Salve’ (also known as the ‘Powder of Sympathy’) whereby a salve (or ointment) was applied to a blade that had caused a flesh wound – rather than to the wound itself (Hood 2009). The understanding at the time was that the laws of sympathy exploited the invisible ‘effluvia’ and influences within which the world vibrated. It was believed that, ‘one could assist the vital spirits of the congealed blood to reunite with the victim’s body and thus heal the wound even at a distance of 30 miles…‘(Thomas 1971: 225, 226).

The ‘cure’ was supported by such leading thinkers such as Robert Fludd, Jan Baptist Helmont & Wilhelm Fabry who attributed the cure to ‘animal magnetism.’ But even by the late 17th century, this magical tradition had barely made any substantial impact upon the population at large, yet simultaneously was beginning to lose its intellectual repute (Thomas 1971: 268).

Sympathetic Magic: Taper Burn Marks –Laws of ‘Imitation & ‘Correspondence.’

Imitation: an ‘imitation’ burn mark is made using the ‘regulated’ flame of a tape under controlled conditions and the person undertaking the procedure focuses intently upon the spot being burnt. The procedure requires intermittent scraping and cleaning out of the charcoal residue to create the bowl shape. The procedure may have been undertaken whilst uttering a blessing, the casting a spell or reciting a prayer.

Correspondence: the burn mark is meant to represent or ‘correlate’ to the marks that would have been left by fire which y possessed the power to devastate a building or buildings.

The impetus behind the burn marks, it would seem, was an attempt remove the ‘random’ possibility of devastating fire by an attempt to control the physical environment appropriately. The burn mark, thus, became an ‘apotropaic’ as the result humans harnessing the power of ‘pyro-technology.’ It has been stated that apotropaism – as a constituent component of cultural practice – can be understood as the ‘technology of protection’ (Boric 2009: 46). In instances where acts of ritual protection occurred, it is the manipulation of an object (a shoe, a taper, a dried cat, a ritually-killed object) which ‘transforms’ it into a magical talisman; it appears to be part of the human condition, therefore, to use technology to provide solutions to problems on both the physical and metaphysical planes.

Throughout the Renaissance it was believed that material things had properties which, in today’s terms, would be understood as ‘magical.’ However, at the same time, Renaissance Hermeticism was a crucial factor in the development of modern science (SL 2022). The study of magic was not separated from ‘rational’ and ‘scientific’ pursuits because the difference between the natural and the supernatural was differently understood at the time (Herva 2012:73). Meanwhile, the practice of folk magic persisted simultaneously alongside Christian practice and scientific enquiry. During this period, neither Catholicism nor Protestantism had managed to eradicate popular folk beliefs, as they were inextricably embedded in the local mode of perceiving and engaging with the material world in everyday life (Herva & Yilmaunu 2009: 234).

In Finland, for example, folk beliefs were neither religious nor scientific; they involved a belief in supernatural powers; they presupposed that there were other than purely ‘mechanical’ ways of manipulating the world. Folk beliefs fused with Christian religion in the medieval and (early) modern period, comprising a syncretic belief system. (Herva (2012), has pointed out that only now researchers applying anthropological methods to this period better understand the thought processes and beliefs of the day. In recent years, researchers have been applying these methods to the Early Modern Period in Sweden & Finland with enlightening results (Herva & Yilmaunu 2009, Herva 2012). This is something that which could increase our understanding of the same period in Britain.

The emergence of post-Reformation Protestantism brought with it the modernist (capitalist) tendency to objectify the world. Protestant reformers rejected magical powers and supernatural sanctions (Thomas 1971: 78). It was this new line of thought which ultimately changed the way in which common people perceived the world and how they engaged with it (Herva & Yilmaunu 2009: 238).

9: CONCLUSIONS & THOUGHTS

From the beginning, the apotropaic potential for taper burn marks has been appreciated, along with the interpretation that they may have functioned as an ‘inoculation’ against fire. The latter appears to be supported by regional folklore (Lloyd 1991, Easton 2012). Further, spatial analysis of each assemblage of burn marks has revealed that concentrations of activity occurred predominantly on the bressummers as well as around timber door and window frames – but not always exclusively so.

The strongest evidence so far for their apotropaic function has come from Timothy Easton’s recording of the bressummer from Anstruther, Scotland. The three-fold stratigraphy of rase-knife symbols, taper burns and apotropaic symbols illustrates a meditated rather than random act (Easton 2012: 46). Its three-fold manifestation relates to the centrality of the number ‘3’ in Christian sacred numerology and its relation to the Trinity. Wright also interpreted the burn marks found at Knole as being a ‘third form’ of apotropaic symbol alongside Marian Marks and incised pentangles (Wright 2015: 5). Hoggard’s (2017: 1) metaphysical reading suggests they form an apotropaic barrier – but on the other side of the spiritual divide. Champion (2017b:13) and Wright (2021) have both suggested that there is no reason why the marks could not have performed a dual function as having been made as both an act of inoculation as well as a visible or ‘overt’ apotropaic intended to guard against supernatural forces.

During my research, I recorded many taper burn marks at the 14th century manor house of Ightham Mote in Kent. As part of a non-intrusive photographic survey of the building I recorded a number of apotropaic marks and symbols. Moving into the Solar Bedroom (Room 131), I found a series of apotropaic marks cut into the stone fireplace. In the same room, a section of panelling has been left open to allow visitors to see the internal timber framing and studs.

The horizontal timber bears a classic tear-drop shaped burn mark – but it is upside down in relation to the timber’s placement – with the narrow ‘tip’ of the flame facing downwards. In proximity, the wooden dowling pegs of the tenon and mortice joint were absent. The most reasonable explanation is that the timber had been inserted at a later date – possibly as a replacement or a repair. It is clear that the burn had occurred prior to its insertion – either in the framing yard during conversion or before having been placed into position.

Closer examination reveals both a saltire ‘X’ and a Marian Mark (in the ‘VV’ form) which have been minutely cut into the burn mark itself prior to it being painted. The letters are only a few millimetres in height and it must have been exacting work to keep the cuts within so small an area (Perkins 2019: 4).

10: WHERE ARE WE NOW?

Even after twenty-five years of research it would appear that further work is required; do we fully understand the motivations of the individuals who made the taper burn marks? What has been ascertained is that taper burn marks can be found on constructional timber in a variety of architectural settings, dating from around the 13th century right through to late 19th century/early 20th century in rural building. Future work on the spatial distribution of the burn marks – allied with building chronologies and dendrochronology dates – may be able to chart the progress of the taper burn marks through a building (or its timber components as they were added or replaced). From this may emerge a ‘pattern’ which in turn would allow us to infer as to whether there was change of ‘intent’ or focus from the earliest to last.

One point of investigation may be as to whether there were ‘favoured’ locations – areas of the house which had received ritual burns in its earliest phase of the house and which remained sacrosanct. Did these locations accrue further burns on a sporadic or annual basis? Did the inhabitants apply further burns to the same locations each year– as Easton has suggested – on the celebration of Twelfth Night? Further, does the fact that biases occur close to sleeping quarters show that the occupants feared nocturnal attack?

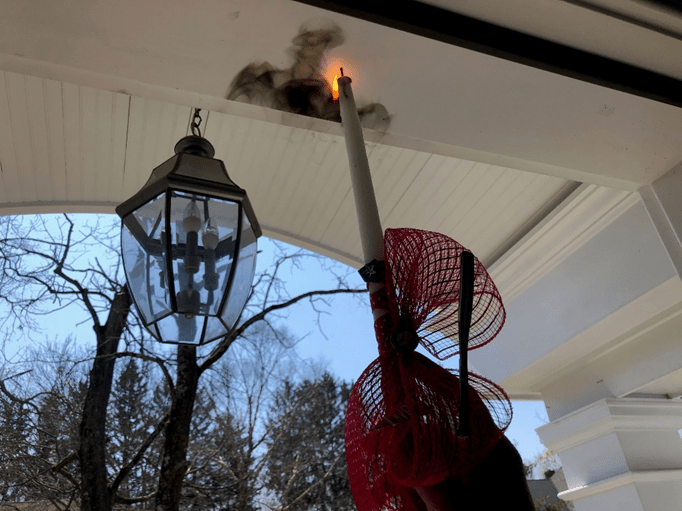

The importance of candles and the role they played within Christian ritual appear to be central to a practice which may have not been directly sanctioned by the church. Rather, it appears to be an example of ‘white’ (sympathetic) magic – a ritual that emerged as a ‘hybrid’ blending folkloric belief within a pseudo-Christian framework. A similar practice can be observed during Holy Saturday as part of the Greek Easter celebrations of Pascha. The ceremony of lighting candles from the remaining Paschal candle is one that is similar to those enacted during Candlemass in England. Candles lit from the Paschal candle are taken home to light the household ones; the house is blessed whilst repeating, ‘Christos Anesti’ (Christ is risen), ‘some only bless the doorways, other walk around with the candle in order to cover a larger area’ (GB 2023).

Again Jesus spoke to them, saying, “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life”. – John 8:12