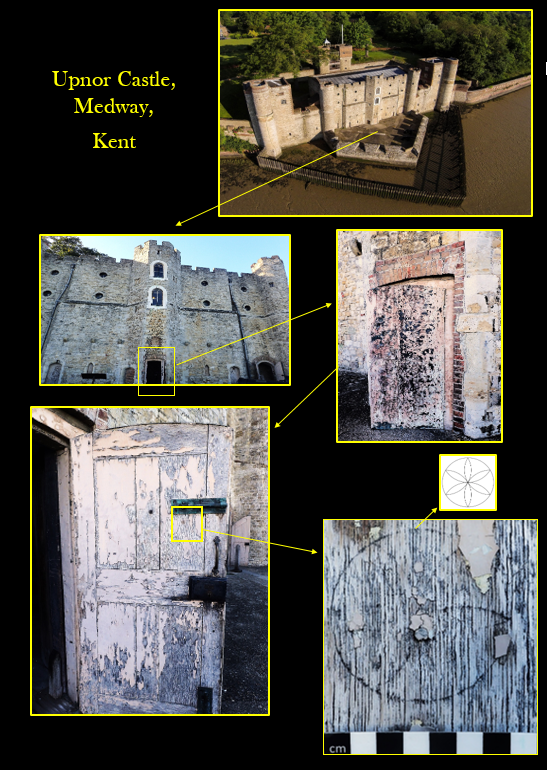

One of the most unusual discoveries that I have made recently is a six-petal rosette (or daisy wheel) graffito that had been incised into the rear of a blast door at the former gun battery of Upnor Castle, Kent. It had been cut into the wood and then hidden under a thick coat of paint – until now.

Upnor Castle, Medway, Kent

England’s Monarchy had always considered the coastal defence of the country to be a ‘necessity,’ as the coasts of Kent and Sussex were adjacent to those of Continental Europe (O’Neil & Evans 1953:1). The first ‘modern’ defences for England’s south coast were instigated by Henry VIII around 1540, whose forty-two new gun batteries (or ‘Devices’) were constructed to protect the ports, anchorages and estuaries of Sussex and Kent (English Heritage 2025).

Upnor Caste from the air. Photo: Phil Pead Wikipedia Creative Commons 2014.

Upnor Castle on the River Medway was constructed between 1559 and 1567 on the orders of the government of Elizabeth I. In 1560, Richard Watts of Rochester was appointed by Elizabeth to be Paymaster, Purveyor and Clerk of the Works for, ‘the erection of a bulwark at Upnor in the parish of Frindsbury for the saveguard of our Navy’ (O’Neil & Evans 1953:1). A defence work was required as Jillyngham Water (and upriver Chatham Docks) were becoming an increasingly important anchorage to the Royal Navy.

View of Upnor Castle from the Medway in 1845, from Curiosities of Great Britain, by Thomas Dugdale, published by L. Tallis, London. Public domain.

It took four years to complete and in 1586 a great chain was hung across the river to prevent incoming ships. This was later bolstered by the addition of a barricade (O’Neil & Evans 1953:2). All this pragmatic activity was concerned with both the physical – and existential – threat of the foreign invader.

The Witchcraft Act 1563

Concurrent with defence building at Upnor and elsewhere Elizabeth faced another threat head on – that posed by supernatural forces. Prior to the new Witchcraft Act of 1563 being passed, a total of five alleged plots against her had been identified. The Waldegrave Conspiracy and the Pole-Fortescue treason being two of the most high-profile among them. It is notable that various forms of magical activity were suspected to be present within all five of the alleged plots (Brennen 2019). Elizabeth herself, no stranger to consulting higher forces other than God to aid her decision making, had consulted the mage John Dee about such matters. He was the service magician who had calculated the most propitious date for her coronation when she ascended to the throne.

John Dee performing an experiment before Queen Elizabeth I. Oil painting by Henry Gillard Glindoni (1852-1913). Date: 1800-1899. Reference:47369i. © Wellcome Collection

The 1563 Witchcraft Act, formally entitled an ‘Act Against Conjuracons Inchantments and Witchecraftes’ was one of the most significant pieces of early modern English legislation. It formally criminalised witchcraft and imposed the death penalty in certain circumstances (Brennen 2019).

Apotropaics at Upnor Castle

A brief survey at Upnor by the author threw up a number of apotropaic devices found within the castle. The nature of the visit did not allow for a fine-grained analysis of each of the structural elements, so this article simply provides a spring board for further research.

Red arrows mark areas where apotropaic marks were found during the survey. From O’Neil & Evans 1953. Reprinted from Kent Archaeological Society Transactions, Archaeologia Cantiana.

The imposing Gatehouse contains a number of ritual taper burn marks, a phenomenon whereby quite deep burns had been applied to the timbers deliberately, in an act of controlled pyro-technology. The general consensus among archaeologists is that the act of making the marks was believed to have provided both an ‘inoculation’ for the building (to counter potential conflagration) and to act as ‘overt’ apotropaics on their own terms (Perkins 2022a). The burn marks were distributed around the fireplaces and a number of deep burns were found on some of the structural timbers.

Imposing gatehouse, the observation deck has now been glassed in for modern visitors. View to the north. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

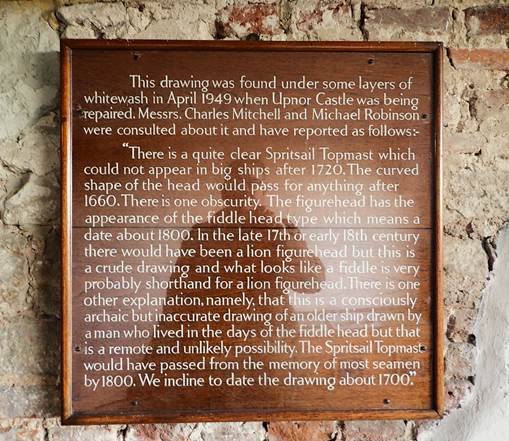

Observation deck, view to the south-east. A wall painting of a ship was discovered in the 20th century, made onto the plaster (it is framed in the top left-hand corner) Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

Taper burn marks on one of the main timbers, view to the south-east. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

Fireplace within the reception room at the main entrance to the Gatehouse, view to the north-west. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

Ritual taper burn marks on the bressummer/lintel above the entrance fireplace, Gatehouse. View to the south-west. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

Graffiti & Wall Paintings

The corpus of graffiti collected during this short visit was, for the most part, illegible, although a number of motifs (arrows, saltires) were recorded.* Of interest was a wall painting of a ship which was discovered in the mid-20th century. Ship graffiti is also a common motif among graffiti corpora culled from coastal locations but its presence in the graffiti of land-locked counties bear out the interpretation that it also possessed a symbolic and apotropaic element. However, it is not surprising to find the rendering of a ship in a building so intimately linked to the sea! The ship at Upnor is feint and difficult to photograph due to the light/reflections in the room.

Ship wall painting in the observation deck. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

The corpus of graffiti in the building is unconvincing if viewed as an attempt to systematically provide apotropaic protection for the structure; a few compass-drawn circles are evident, the one on the newel post of the spiral staircase may have targeted a key structural element. The circle, when applied as an apotropaic, draws on a range of Christian associations and its religious iconography (Perkins 2022b).

Compass drawn circle (c.8cm diameter) on one of the support timbers. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

Compass drawn circle (c.4cm diameter) on the newel post of the spiral staircase. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

Spiral stair which links the upper floor of the Main Building to the Water Bastion. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

In May 1668 it was decided that Upnor Castle should be converted into a Magazine. It is likely that it was around this time that the doors (and window shutters) were sheathed in copper to reduce the risk of sparks, as the building held so much gunpowder. However, from the 17th century there is a gap in the documents up until 1891, so it is difficult to tell when other changes occurred during this time (O’Neil & Evans 1953:7).

Window shutters sheathed in copper. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

Some of the doors and shutters have the royal cipher (or monogram) ‘G R’ marked out in nail heads, suggesting that they were added during the reign of King George IV (1762-1830). It is difficult to decipher the date on the below example but it appears to start ’17….’

One of the copper-sheathed doors designed to prevent sparks when the building was converted into a gunpowder Magazine. Photo: © W Perkins 2024

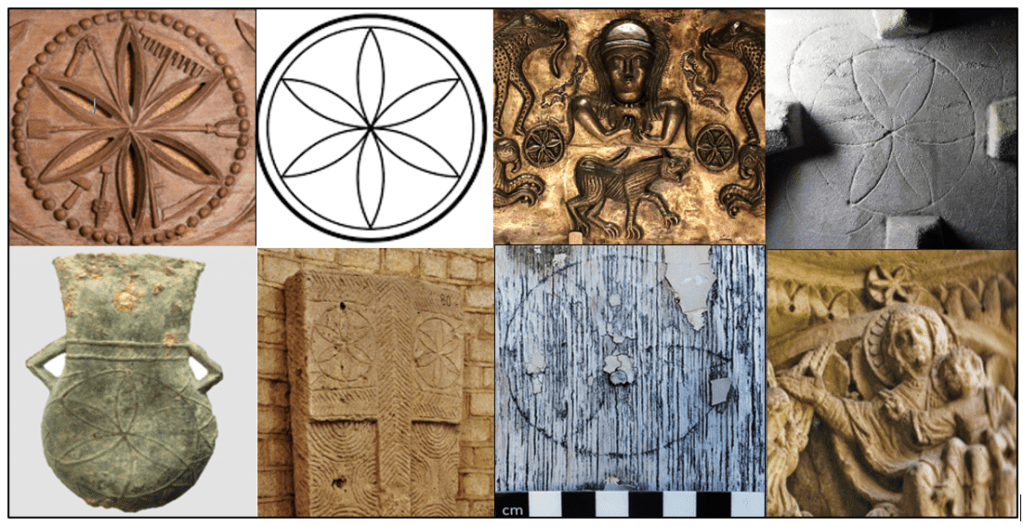

By far the most intriguing graffito is the six-petal rosette on the rear of the blast door which services the Water Bastion (or gun platform which juts out into the river Medway). The six-petal rosette – sometimes referred to as a hexafoil or daisy wheel – is a prominent motif among graffiti corpora and is still held to possess an apotropaic function among most archaeologists (Perkins 2022b).

However, taking the type of carpentry employed to fabricate the door, it appears more like a 19th century construction – it does not look like a door which has withstood 300 years of service! Work still needs to be done on dating the door and I await a request regarding a material survey of the castle to be answered by its owners.

The question , therefore, is whether the motif was added to the blast door as a layer of protection to counter against supernatural attack in the 18th century, or if, by the 19th century, it had been added simply as a ‘good luck’ charm by the garrison stationed at the castle.

In any survey, it is important to view any potential apotropaics within their own specific archaeological context. In this instance, they are located within an ostensibly military building but one which also provided a home for up to 86 individuals for long periods –all of whom would have brought their own personal folk traditions and beliefs – as well as their hopes and fears – to the castle.

If one looks at the evidence as a whole, taking the corpora of graffiti present; the ship wall painting and the various ritual taper burn marks they can be considered to have been (both individually or collectively) accrued as wards against misfortune – but not necessarily ones present all at the same time!

Wayne Perkins

BA (Hons), ACIfA

London, October 2025.

- = A number of initials and dates, some of the 17th century were recorded by O’Neil & Evans, pictures of which are included in their report.

Learn more about the six-petal rosette in my next lecture –

Further reading & links

Brennen, L (2019) Parliaments, Politics and People Seminar: The Political and Religious Origins of the 1563 Witchcraft Act. The History of Parliament. British Political, Social & Local History.

English Heritage (2025) Deal Castle: A Glorious Beginning

O’Neil, B H & Evans, S (1953) ‘Upnor Castle, Kent: History’ in, Archaeologia Cantiana, Transactions of The Kent Archaeological Society.

Perkins, W (2022a) Incendiary Behaviour! Apotropaics The Rough Guide #1: Taper Burn Marks

Perkins, W (2022b) Return to the Source

Wellcome Collection (2025) John Dee performing an experiment before Queen Elizabeth I. Oil painting by Henry Gillard Glindoni 1852-1913. Date: 1800-1899 Reference: 47369i.