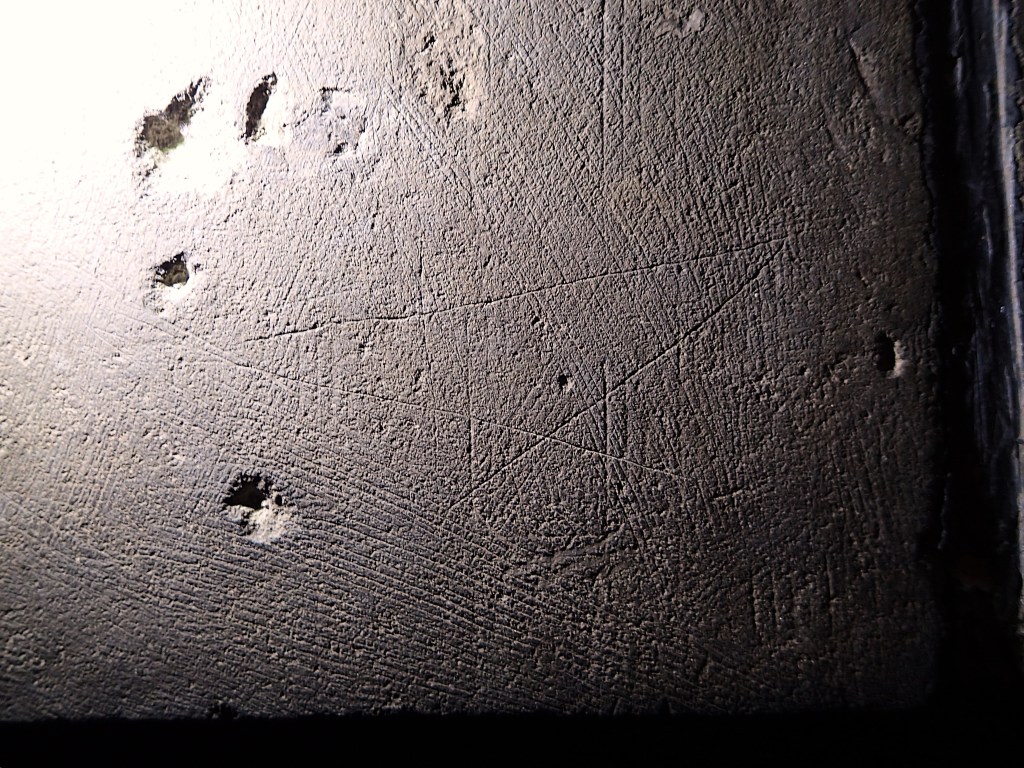

A fireplace, half a millennium old and re-built in the foyer of Southend-on-Sea’s museum still bears apotropaics…perhaps embracing the concept of ‘imperfection’as a sign of Christian humility...

This impressive fireplace (once a series of stacked fireplaces) was originally built in the 15th century for a house called Reynolds, formerly located in West Street, Prittlewell, Essex (Southend Museums 2026). The house was demolished in 1906.

To preserve the structure, the fireplace was dismantled and transported to the Victoria & Albert Museum in South Kensington, London and re-built. If that isn’t surprising enough, in 1975 it was dismantled for a second time and re-erected here, in the foyer of the museum at Southend.

Like The Circles That You Find…

Amazingly, not only has the fireplace survived this constant re-building but a number of apotropaic marks have survived the process, including two ‘faux’ consecration crosses cut into the masonry lintel. Feint and delicately cut, they can just about be seen with the naked eye…if you know where to look…..

Photo: © W Perkins 2026.

It is strange, perhaps to find consecration crosses on masonry belonging to a secular building, as the act of consecration was one which could only be undertaken by a Bishop. The first archaeologist to note the use of ‘holy signs’ in secular contexts was Timothy Easton, back in 2015 in his article, ‘Like The Circles That You Find.’ On consecration crosses, he stated,

“Traditionally, these were added to the walls of new churches and also to later additions such as aisles. Twelve were added to the inside and another twelve to the outside . Once all was ready, the bishop would arrive with great processional ceremony and, after three circuits of the interior, would start the lengthy service. Steps were mounted before each one and the symbol would be blessed with holy water. This was part of the process to placate the spirits in a disturbed holy place.”

“It is quite possible that scribed symbols were added to chimney lintel beams for a similar reason. The major disturbance of inserting large stacks with hearths to existing houses meant huge upheavals within a familiar space and an informal secular form of consecration could have taken place to settle the home once more.”

Easton 2015:53-4

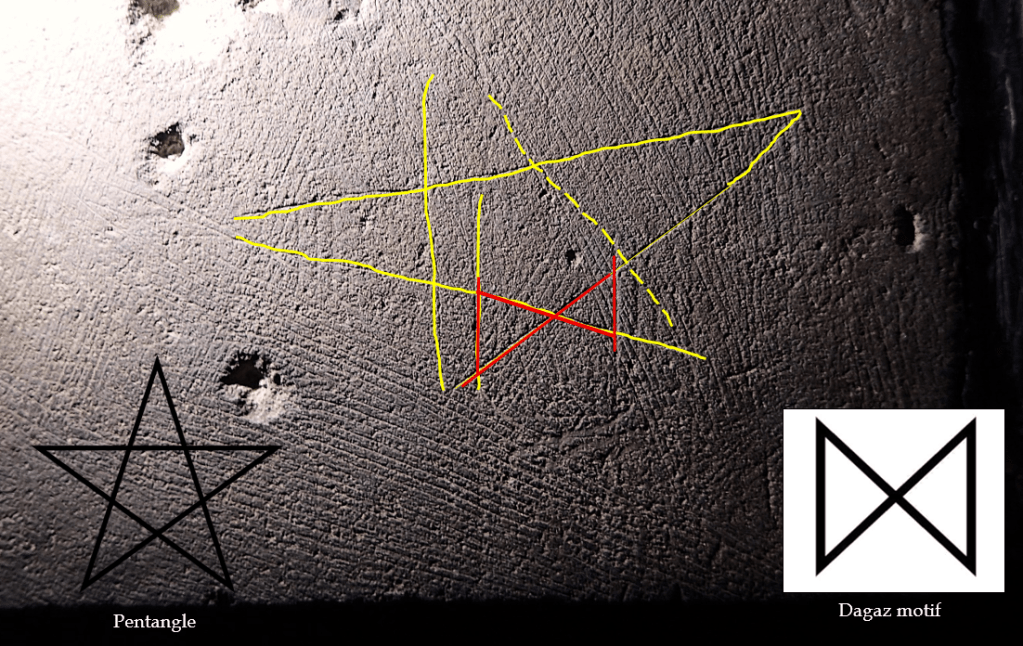

The other mark seems to be a ‘Dagaz’ symbol, which has been modified to create a pentangle (or the other way around)…

The Dagaz Symbol

The ‘Dagaz’ motif is created from the use of a central saltire (or cross) closed off at each end, which produces two opposing triangles. The ‘X’ is the central component as it is for many other rune-derived symbols along with the dagaz rune (sunlight, protection), such as Ing/Inguz (well-being, the hearth) and Othala/Odal (home, prosperity, family) (Wood 2019). Nevertheless, it is important to differentiate between actual runes and symbols derived from runes.

In the north of England in particular, their provenance in vernacular architecture seems to be attributable to the pre-Christian runic script introduced in north-east England in the later part of the first millennium, The runic symbols entered Britain primarily in Northumbria through the Anglo-Saxon cultural package. In old Scandinavia the diagonal cross was often placed on the gable apex of the building (Billingsley 2020: 27).

‘Perfect’ is the enemy of good

There is a phenomenon known in graffiti studies whereby recorded examples of some compass-drawn circles show that they are incomplete. This may have been intentional as, whilst the person creating the circle may have been invoking the protection of the Virgin, it may have been seen as presumptuous to try and improve upon her ‘perfection.’

In Western Christian symbolic art, the circle – formed without a break or angle – was seen as embodying perfection. It was believed that the circle was a symbol of eternity and heaven and represented the Virgin’s purity and unbroken virginity (Stemp 2010). The circle could also represent a globe; the symbolic sphere of the Earth. When depicted in its smaller form, it symbolised fruit. In this way, Mary came to represent the new Eve, a sign of redemption (Bourlier 2013).

Cross-culturally, human behaviour which displays this hesitancy to affront the creator is known from elsewhere….

The Anishinaabe

The Anishinaabe are described as a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States. It includes the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Mississaugas, Nipissing, and Algonquin peoples, known for their intricate beadwork particularly regarding their medicine bags (Bowler 2020:26). Within the weave of their medicine bags they include a ‘spirit’ bead. A spirit bead is an intentional flaw created within an otherwise perfect piece of beadwork to demonstrate humbleness before the Creator, and to show that nothing on Earth given to us by the Creator is perfect, including ourselves (Scofield et al., 2011). Spirit beads have also been referred to as humility beads (Bowler 2020:26).

The Navajo Nation

Jill Ahlberg Yohe, a cultural anthropologist, goes into great depth on this topic in her work “Situated Flow: A Few Thoughts on Reweaving Meaning in the Navajo Spirit Pathway”. Navajo Nation conceptualized the ch’ihónít’i as being a purposeful mistake in two ways. In the first case, the spirit-line is woven into the textile as an intentional “flaw,” a symbolic path for the survival of the weaving tradition to continue into the future. The second interpretation is that the spirit-line is a deliberate design element incorporated by the weaver as a valued expression of modesty. Because nothing in life is perfect, some say, the weaver adds the spirit line to materialize the positive attributes of human imperfection and humility (Jenkins 2022).

© 2016-2017 Regents of the University of Michigan

Taoists

Wabi-sabi is a world view that embraces imperfections as being a part of the perfection of nature. Originating in Taoism during China’s Song dynasty (960-1279) before being passed onto Zen Buddhism, wabi-sabi was originally seen as an austere,restrained form of appreciation (Jenkins 2022).

Phukari

Carla M. Sinopoli explained, ‘Phukari is a type of folk embroidery that originates from Punjab region of India and Pakistan. Deliberate mistakes are well documented in this art form, “…women sometimes introduced small colour or pattern changes into their work. Some were added to protect the shawl’s wearer from the evil eye. Others were stitched to mark important events that occurred during a textile’s creation, such as the joy of a baby’s birth or grief over a relative’s death” (Jenkins 2022).

Whilst it is impossible to simply take one culture’s norms and transpose them onto the motivations behind the creation of graffiti symbols of Christian Europe, we can at least acknowledge that this behaviour may be a uniquely human trait, tied up with ideas of godhood and the sacred.

The Reynold’s fireplace has somehow survived its rebuilds and removals and may still be able tell us something about the mindset of the inhabitants of the house. The consecration marks may have been added as ‘closure’ following the insertion of the fireplace. The removal of any wall in the house would have threatened the spiritual ‘integrity’ of the building and perhaps, in the minds of its inhabitants, made it vulnerable to outside forces.

Wayne Perkins

January 2026

New for 2026! Available for pre-order!

A Consensus of Symbols

Patterns in Ritual Building Protection

By (author) Wayne Perkins

References

Billingsley, J. (2020). Charming Calderdale: Traditional Protections for Home & Household. Hebden Bridge, UK: Northern Earth.

Bowler, S (2020) Stitching Ourselves Back Together: Urban Indigenous Women’s Experience of Reconnecting with Identity Through Beadwork. By Shawna Bowler B.A., University of Manitoba, 2005 B.S.W., University of Manitoba.

Easton, T. (2015). ‘Like the circles that you find’ in, Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings Magazine, Winter.

Jenkins, E (2022) Hidden Mistakes in Crochet: Irish Legend or American Myth?

Less Than Perfect (2017) Weaving a spirit pathway.

https://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/less-than-perfect/deliberate.php

Perkins, W (2022) Return To the Source.

Scofield, G., Farrell Racette, S., & Briley, A. (2011). Wapikwaniy: A Beginner’s Guide to Metis Floral Beadwork. Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute

Stemp, R. (2010). The Secret Language of Churches and Cathedrals: Decoding the Sacred Symbolism of Christianity’s Holy Buildings. London: Duncan Baird.

Wood, C. (2019). X marks the post: An exploration of a magically protective sign. Quest for the Magical Heritage of the West, 198: 13–26.