When referring to the Virgin Mary, most of us are familiar with her title, the ‘Queen of Heaven’ but in the Middle Ages the appellation ‘the Empress of Hell’ held equal weight. How did she get gain this remarkable title and what did it refer to in Christian theology?

[Main image: Plate 18: Mary beating the devil in the shape of a beast, Martyrology of Notre-Dame des Près, Valenciennes, BM, 838, f.097v, 1275-1300, Arras, France. Institute for Research and History Texts. Image sourced by V Corcoran. Public domain]

Interdisciplinary Approaches

In the church of St. James the Great in Snitterfield, Warwickshire (Plates 1 & 2), I found a ‘ragged staff’ motif cut into one of the north piers of the nave (Plates 3 & 4). Alongside it, there were a number of other graffiti symbols which were concentrated on that particular pillar in the north aisle. The combination of symbols – some of which were apotropaics – suggested that it may have become the foci for devotional graffiti, possibly because it was once the location to a side altar or chapel. Investigations are ongoing.

In 2022, historian and replica pilgrim badge maker Colin Torode (of Lionheart Replicas) began to look afresh at representations of the ragged staff on pilgrim badges rather than at their graffiti counterparts. Reviewing his collection, he found that many examples bore a centrally-placed cross and the Latin inscription, ‘Maria Ora’ (Mary, pray for me) (Plate 5). He compared the badge to one in the British Museum catalogue, which comprised three symbols, two of which flanked the ragged staff motif. By appraising the symbolism of each, he believed that it was possible to see that they formed a sort of ‘narrative’ (Torode 2022).

Like so many posts on this blog, this is another example of how cross-disciplinary approaches to archaeological interpretation can pay dividends.

St James the Great, Snitterfield, Warwickshire

The parish church of St James consists of a chancel, nave (of four bays), north and south aisles and a tower (Figure 1). The chancel is of the 13th century, the nave of the 14th and the tower was built in two distinct phases, interrupted by the Black Death (NCT 2022, Styles 1945). Of particular note is the 14th century font with its projecting carved heads (Plate 6).1

The Bear & Ragged Staff

The ragged staff symbol is a widely known as a recognisable component of the ‘bear and ragged staff’ motif which was the heraldic emblem or badge associated with the Beauchamp family and the Earldom of Warwick. It is one of the most immediately recognisable medieval livery badges and is still used today as the Warwickshire County badge (Plate 7) (Torode 2022, Champion 2017).

However, the ‘ragged staff’ motif – without its attendant bear – appears regularly within the corpora of graffiti (Champion 2017). Initially, its frequency within graffiti collections was thought to be the result of the Beauchamp’s retinue ‘tagging’ churches and other medieval buildings. This interpretation soon became untenable (Torode 2022). Examples of ragged staff graffiti have been found from Dorset to Norfolk and from Kent to Northumberland (Champion 2015:117). Archaeologist Matthew Champion asked why the livery badges of the other great medieval noble families – the Howards, de Vers, Stafford’s’ and the Buckingham’s were not equally represented. The unique presence of the ragged staff among graffiti corpora suggested that the use of livery motifs in the context of graffito was not regularly practiced, making the ragged staff an exception (Champion 2015:117).

In Violet Pritchard’s mid-20th survey of ‘English Medieval Graffiti’ the presence of the ragged staff within her recorded corpora suggested that there was more to the symbol than its association with heraldry (Pritchard 1967, Champion 2015:117). Further, it had often been found in association with other religious imagery and other well-known ‘ritual protection marks’ which – by association – suggested a possible apotropaic function. Among researchers, there has always been a sense that the badge had a deeper, religious function whose origin had been forgotten (Champion 2017, Torode 2022).

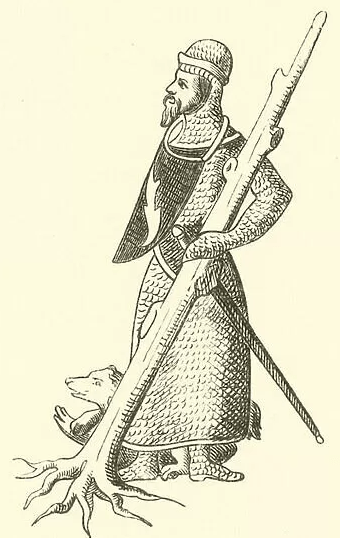

For some time, the deeper meaning behind the symbolism of the staff had eluded researchers, and a number of differing interpretations had been forwarded. It was suggested that the ragged staff motif referred to Morvidus (an early and legendary Earl of Warwick) who is said to have slain a giant, ‘with a young ash tree torn up by its roots’ (Plate 8) (Turnbull 1995).

Meanwhile, the emblem of the bear was believed to refer to Urse d’Abetot (c.1040-1108) (Latin: Ursus = bear). D’Abetot was the 1st Feudal baron of Salwarpe, Worcestershire and served as the Sherriff of that county (Plate 9) (Round 1885).

The emblem was subsequently adopted by Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester (1532- 1588) of Kenilworth castle in somewhat different form (Plate 10).

The Staff of St Christopher

In Christian art, the staff was a symbol often associated with pilgrims, pilgrimage and the saints. The imagery of the ragged staff bears a strong resemblance to the staff of St Christopher; regarded as the ‘key’ saint in the iconography of the medieval church (Champion 2015: 118). St Christopher’s beginnings are cloaked in mysterious legend, whose Feast Day is celebrated on the 25th July (Plate 11). He is said to have been martyred AD 250-1 during the reign of Decimus; beaten with rods, pierced by arrows and decapitated (Mersham 1913).

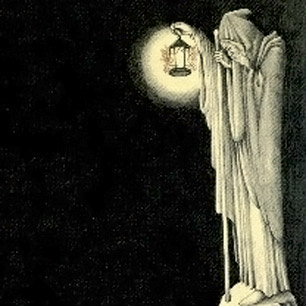

The 13th century ‘Golden legend’ (compiled around 1259-1266) determined the portrayals of Christopher in Western art. Described as a pagan giant called Reprobus (the reject) he determined to serve the Lord by transporting people across an unfathomable river. One day, he carried what appeared to be a child who gradually grew heavier as he forded the river. In due course, the child was revealed to be the Christ child. A hermit, standing nearby on the riverbank who had witnessed the event christened him, ‘Christophorus’ (Christ bearer) (CI 2022) (Plate 12). In the story, the Christ-child tells Christopher to plant his staff in the ground as it will, ‘bear leaf in the morrow.’ Common depictions show St Christopher carrying the child who is holding an orb. His staff can be seen already in leaf whilst fish swim around his feet and a hermit on the river bank, holding a lantern, points the way.

Traditionally, St Christopher’s image was painted upon the interior north wall of the church or in a position which could be viewed from the south door. For pilgrims looking upon his image could consider themselves to be safe from ‘sudden’ and ‘unexpected’ death (Champion 2015: 118).

This idea is illustrated by a Norman-French inscription to be found under a wall painting of St Christopher in Woodeaton, Oxon, it reads,

‘ …he who sees the image shall not die an ill death this day’ (Healey 2022).

An ‘unexpected’ or ‘bad’ death would be one which was sudden, violent or ill-prepared for, leaving the living unable to satisfy the conditions of a successful rite of passage. It would likely result in one becoming a ‘revenant.’ Disruptive acts such as murder or witchcraft enabled the return of the deceased as, ‘the state of the body was seen as the manifestation of the state of the soul.’ Decay was one of the greatest signifiers of sin and a restless, pestilent corpse was an unambiguous reflection of the state of the dead person’s soul. Bad death was considered polluting and contagious and required extra ritual performance to bind the deceased to heal social schism and therefore restore order to the community (Gordon 2014: 57).

The use of St Christopher’s image in this way persisted until 1549 when Molanus (a prominent catholic theologian) decreed the image to be ‘superstitious.’

Tree of Jesse

Another line of research led to the ragged staff being identified with the Tree of Jesse (Plate 13). Images of entwining and sinuous trees and branches dominate depictions of the Tree of Jesse which is believed to be a symbolic representation of the family tree of the bloodline of Christ (Champion 205: 118). By the 14th century, this was often depicted as a tree composed of fecund growth.2 The Tree of Jesse originates in a passage in the biblical Book of Isaiah which describes – metaphorically – the descent of the ‘Messiah’ to Earth, who is accepted by Christians as referring to Jesus.

“And there shall come forth a rod out of the root of Jesse, and a flower shall rise up out of this root…”

Isiah xi, 1, 2 & 10.

The patriarch Jesse belonged to the royal family, which is why the root of Jesse signifies the lineage of kings. He is often depicted larger than the other figures, asleep or reclining at the base of the image, where the tree emerges from his navel. As to the rod (or trunk), it is said to symbolise Mary as the flower symbolises Jesus Christ (Male 1913:164-5). The first representations of the passage in Isaiah, (from about 1000 AD in the West), show a “shoot” in the form of a straight stem or a flowering branch held in the hand most often by the Virgin, or by Jesus when held by Mary, by the prophet Isaiah or by an ancestor figure. The earliest example we have is an illuminated manuscript which dates from the 11th century.

Although some depictions of the tree show the ‘cut branches’ along its length, the deviation from the classic ragged staff pilgrim badge and graffiti iconography seems too great. However, that is not to say the motif does not also draw – albeit only by reference or inference to – the Tree of Jesse.

Decoding the Symbols

Returning to the vexed question as to the true meaning behind the ragged staff motif, we return to the evidence provided by pilgrim ‘signs’ or badges. Torode’s parallel interest in collecting historic graffiti from medieval buildings provided him with an opportunity to make comparisons between the examples that he had found cut into masonry and the pewter pilgrim badges that he had in is possession. Fortuitously, it is one of the few cases in graffiti studies where the graffito matches a more widely used religious symbol. In the case of the ragged staff badge, there is usually a distinctive cross placed centrally to the main trunk of the tree. In some of his examples he could also make out what appeared to be strange stem or new branch which appeared to be growing from the staff’s cut base (Torode 2022).

It soon became clear that the motif represented a tree which had been cut at the base (many examples appear to show the base of the ‘chopped’ trunk) as one which has been intentionally felled. From the base of the cut trunk, new growth or a new shoot had emerged. A freshly coppiced tree may to all intents and purposes appear to be dead but will remarkably spring back into life (Torode 2020).

Christ’s Sacrifice & Resurrection

For Torode, the analogy of a tree ‘cut down’ in its prime, followed by new growth seemed to provide the suitable symbolism for the sacrifice of Christ, followed by his resurrection (Torode 2022). It seemed to chime perfectly with the tenets of renewal and rebirth in the Christian origin myth (Plate 15).

Although the analogy may appear prosaic, coppicing (and pollarding) was practiced across the medieval world. The widespread and long-term practice of coppicing as a landscape industry had been of significance in many parts of lowland temperate Europe and practiced by many. It was an action which would have renewed one’s faith in nature’s (and therefore, God’s) ability to regenerate and grow back stronger.

Marian Connections

With this in mind, it left only the centrally placed cross on the staff and the Marian dedication to decipher. This final piece of the jigsaw fell into place whilst he was perusing the British Museum’s catalogue of pilgrim badges. He revisited a badge he had seen many times; a ragged staff badge but composed of three separate elements which appeared to be linked (Plate 16). In the centre of the badge was a tree with its limbs lopped off but with its roots intact. To the left was a ragged staff (complete with its cross) and on the other side, an eagle with its wings displayed – a well-known motif used in Christian sacred art as a symbol for resurrection. The badge depicted a narrative of life, sacrifice and resurrection, with reference to the Trinitarian formula. It was the perfect analogy for Christianity’s central tenet, Christ’s life, sacrifice and resurrection (Torode 2022).

The only element that the interpretation failed to account for the ‘Maria Ora’ prayer and cross on the ragged staff itself. Rather than simply existing as a Marian blessing, Colin realised that it referred to the oft-forgotten role that the Virgin’s once played as a great intercessor for the dead as the ‘Empress of Hell’ (Torode 2023).

The Harrowing of Hell

The Apostles Creed, a fourth century text, states that the Harrowing of Hell (Latin: Descensus Christi ad Inferos, “the descent of Christ into Hell” or Hades) refers to the period of time between the Crucifixion of Jesus and his resurrection (Plate 17). In triumphant descent, Christ brought salvation to the souls held captive there since the beginning of the world (Corcoran 2020, Warren 1910). Christ the redeemer, intercessor and saviour.

The Virgin Mary: Empress of Hell

In the Middle Ages, Christians also sought the protection of a different intercessor, one who would descend into hell to shame, debate, and even physically assault the devil to save people from damnation: the Virgin Mary (Corcoran 2020). In Christian practice, intercession or intercessory prayer is defined as the act of praying to a deity on behalf of others, or asking a saint in heaven to pray on behalf of oneself or for others. This act has sometimes manifested itself concentrations of graffiti on and around effigies and in proximity to former chantries, side chapels and shrines (Perkins 2022).

According to Corcoran (2020), Mary’s intercession always included two components: the initial petition for her aid, followed by her intercession with God or her son Jesus on behalf of the petitioner. The miracle stories that emerged in the later Middle Ages increasingly depicted Christians who were more comfortable praying to Mary instead of Christ. Mary’s mediating role was so powerful, it seems, that some viewed her intercessory abilities as separate from Christ’s power (Corcoran 2020) (Plate 18).

One of the most vivid descriptions appears in the writings of William of Malmesbury who wrote that, in order to protect a drunken monk, Mary beat the devil with a stick multiple times,

“re-doubling her blows and making them sharper with words, ‘Take that, and go away. I warn you and order you not to harass my monk any more. If you dare to do so, you will suffer worse.’”

William of Malmsbury (12th century), quoted in Corcoran (2020).

Written c. 1135 by the Benedictine monk, historian and scholar William of Malmesbury (d. 1143), ‘The Miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary’ belongs to the first wave of collected miracles of the Virgin, produced by English Benedictine monks in the 1120s and ’30s. It is considered to be an important document in the history of Marian devotion in medieval Europe.

According to Corcoran, the late medieval stories of Mary as Queen of Heaven and Empress of Hell, ‘shaped a figure who was at once an accessible intercessor and a powerful force in determining the fate of individual souls.’ In terms of the evidence in relation to pilgrimage,shrines on the Continent sprang up around this theme, with pilgrim badges often incorporating ragged staffs (Torode 2022). Although the term, ‘Empress of Hell’ fell out of use at the end of the Middle Ages, Catholics have continued to view Mary as an effective intercessor.

Ragged Staff: Cross, Marian Devotion & the Resurrection

It appears that one of graffiti’s more enigmatic symbols may have finally been decoded and more fully understood. The symbol of the ragged staff itself could be seen as a kind of ‘shorthand’ for the more complex ideas contained in the triple-image ‘narrative’ badge of tree, staff and eagle.

The cross and Marian prayer found on the ragged staff pilgrim badge referred to a partly forgotten role that the Virgin Mary once played as intercessor to rescue souls from hell and damnation. Symbolic references to both Christ’s ‘transition’ during the time depicted by the Harrowing of Hell and to St Christopher’s flowering staff seem to suggest strength taken from a tripartite combination of reflective references. It is a pertinent reminder, therefore, of the multiplicity of meanings and symbols which may be contained in the religious motifs found in both medieval graffiti and pilgrim signs (badges).

Wayne Perkins June 2023

BA Hons (Archaeology)

ACIfA (Associate Chartered Institute for Archaeology

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Notes

1. One of the most interesting features of the church is its 14th century font, which, like others in Warwickshire, has carved heads round the base of the bowl. Time has weathered and chipped at these faces so that their expressions are enigmatic, perhaps ensuring that they are as powerful now as when they were first carved. It is octagonal; the bowl has upper and lower mouldings and a hollow below in which are projecting carved heads at the angles; these are of men of various callings: one has a bishop’s mitre, another is a knight, others have caps, probably academic and legal, and another a close-fitting hood. The stem and chamfered base are plain.

2. The Tree of Jesse. While he is sleeping, a tree is growing from Jesse’s body with on it the twelve Kings of Judah, the ancestors of Christ, and Mary with the Christ child in the top. The kings are: David, Solomon, Rehoboam, Abijah, Asa, Jehoshaphat, Jehoram, Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, Hezekiah and Manasseh. On either side of Jesse two prophets are standing, probably Isaiah and Jeremiah. To the left a nun in a white habit, probably from the Order of St.Mary Magdalene, is kneeling. She is the donor of the painting.

Acknowledgements & Afterword

The author refers to the scholarly detective work undertaken by Colin Torode of Lionheart Replicas who patiently picked apart the imagery to supply such a satisfying interpretation of the ragged staff badge.

In a light-heartedsign off to his post on Facebook, Colin Torode has announced that, due to his new interpretation, the ragged cross pilgrim sign has been moved from the ‘secular’ badge category to the ‘pilgrim and devotional’ badges range on his website (Torode 2023).

The author also has to concede that this short article would not have been possible without Vanessa R Corcoran’s engaging piece on the Queen of Heaven, Empress of Hell on the Contingent Magazine website. It was based upon her far-reaching PhD, ‘The Voice of Mary: Later Medieval Representations of Marian Communication (2017).

Vanessa Corcoran is Academic Counsellor in the office of the College Dean at Georgetown University. Her research interests include the medieval cult of the Virgin Mary the intersection of gender and popular religious practices, and the textual representations of medieval women’s voices

Bibliography

Champion, M (2015) Medieval Graffiti. Ebury Press.

Champion, M (2017) ‘Ragged Staff’ in, Medieval Graffiti Group Volunteers Manual

Christian Iconography: St Christopher

https://www.christianiconography.info/index.html

Corcoran, V (2017) ‘The Voice of Mary: Later Medieval Representations of Marian Communication.’ Dissertation for the School of Arts & sciences at the Catholic University of America.

Corcoran, V (2020) ‘Queen of Heaven, Empress of Hell’ in, Contingent Magazine

Gordon, S (2014) ‘Disease, Sin & the Walking Dead in Medieval England c.1100-1350: A Note on the Documentary & Archaeological Evidence’ in, Medicine, Healing & Performance. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Historic England (2022) St James the Great, Snitterfield, Warwickshire

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1382171?section=official-list-entry

Malmsebury, W (c.1135) ‘Miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary.’ Volume 1 of Boydell Medieval Texts. Author Wilhelm (von Malmesbury). Editors Rodney M. Thomson, Michael Winterbottom. Publisher: Boydell & Brewer, 2015.

Marshall, A (2018) Medieval Wall Painting in the English Parish Church.

https://reeddesign.co.uk/paintedchurch/woodeaton-st-christopher.htm

Mersham, F (1913) St Christopher

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/St._Christopher

Perkins, W (2022) Intercessors, Folk Saints & Effigies of Notable Pious Individuals: Foci for Graffiti? Ritual Protection Marks & Ritual Practices website.

Pritchard, V (1987) English Medieval Graffiti. Cambridge University Press.

Round, J H (1885) ‘Urse d’Abetot’ Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900. Volume 58

Styles, P (1945) ‘Parishes: Snitterfield’, in A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 3, Barlichway Hundred, pp. 167-172. British History Online

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/warks/vol3/pp167-172

[accessed 3 June 2023].

Torode, C (2023) ‘The Ragged Staff Revisited.’ Lionheart Replicas blog

https://www.lionheartreplicas.co.uk/

Turnbul, S (1995) The Book of the Medieval Knight, Arms and Armour.

Male, E (1913) The Gothic Image, Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, p 165-8, English trans of 3rd edn, 1913, Collins, London.

https://archive.org/details/gothicimagerelig0000male/page/164/mode/2up

Spencer, B (2010) ‘Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges (Medieval Finds from Excavations in London).’ Boydell Press; Illustrated edition

Warren, K.M. (1910). Harrowing of Hell. In, The New Advent Catholic Encyclopaedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07143d.htm

[Retrieved May 21, 2023]

Wayne – Thanks very much for your excellent scholarship in research and writing about the Virgin Mary’s Ragged Club; very well done and a great read. “Empress of Hell” … just when I thought I had heard everything about the Holy Mother!

LikeLike