Shoe Outline Graffiti Discovered at St Mary the Virgin Church, Chalk, Kent

A recent survey recorded ‘shoe outline’ graffiti on a lead wall plaque in a church in Kent. Although this type of graffiti is often thought to be ‘commemorative’ in nature, it also appears to have an apotropaic function. Is there a connection between shoe outline graffiti and the phenomenon of deliberately concealed shoes sometimes found in ancient buildings?

The Village of Chalk & Its Church

The church of St Mary appears to be quite separate from the small cluster of buildings which comprise Chalk village itself (Torode 2023). Its location – on an area of raised ground or small hillock – may have been chosen for its proximity to the Lord of the Manor at East Court Farm as well as an ancient trackway that once linked the River Thames to the surrounding inland areas (Bull 2023). It may be outside the heart of the village but it is located adjacent to the old London to Dover Road, (A2) – the connection between London and the sea trade routes to Continental Europe. It also stands close to what was one of the toll gates for the toll road that opened up between Northfleet and Strood. Apparently isolated, it stands on an important ancient thoroughfare and a communication network. Chalk parish church building is a Grade: II listed building, dedicated to Saint Mary the Virgin (Kent Past 2023) (Plate 1).

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

Chalk: Saxon Origins

Chalk comes from the Anglian word ‘calc’ meaning ‘chalk, lime, limestone’; therefore, ‘chalk’. The Domesday Book records Chalk as Celca, and the Textus Roffensis as Celca and Cealces. (Kent Past 2010)

The site of the church we see today was occupied by at least two previous churches (GBC 2023). The present structure is of Early English style dating from the 11th to 13th centuries with a late 12th century north aisle (GBC 2023) (Plate 2).

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

It is known from documentary evidence that a church building existed here for the Synod of Chalkhythe in AD 785 (PCC 2023). There is a survival of herringbone masonry in the chancel which hints at its Saxon origins (Historic England 2023). The church was later recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 (Torode 2023).

Medieval Rebuilding

By the end of the 12th century, a north aisle had been added to both the nave and chancel. The south aisle was built in the following century, although it was duly demolished in 1759 (Bull 2023, Kent Past 2023). The church has a nave of three bays with north aisle, the western end of which is now a vestry for choir and priest. On the south side of the chancel is a 13th century sedilia and piscina with shelf. Inside the west door is a holy water stoup (GBC 2023) (Plate 3). The present structure is mainly of Early English style (PCC 2023, GBC 2023). The church of Chalk once belonged to the Benedictine priory of Norwich and in the 15th year of King Edward I (AD 1239-1307) it was ‘valued at thirty marcs’ (Halstead 1797).

The church was greatly enlarged during the 14th and 15th centuries with a bell dated 1348 originally part of the original structure (Historic England 2023). In 1797, Edward Hasted described the Chalk church as consisting of ‘two isles and two chancels, having a square tower at the west end, in which are three bells.’

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

The west tower forms an important landmark, and is of three, un-buttressed stages with a prominent north-west stair turret (Plate 4). Both the tower and the turret have embattled parapets. The tower has foiled, c.15th century lights. The tower with its projecting stair turret is typically Kentish addition (GBC 2023, BLB 2023), and acted as an important landmark for shipping and also for those travelling the Dover to London road (Vigar 2023).

Public domain: Wikicommons. Photo: © Pauk 2011.

Graffiti Survey

The author visited the church in 2023 to undertake a survey of any surviving historic graffiti. A combination of factors – some relating to the type of stone employed and other architectural alterations – meant that the yield was very low indeed. It is notable that, with some churches and in some cases, the graffiti count can be low in number or completely absent altogether. It is not always easy to account for this disparity. Apart from a possible mason’s mark there was only a devotional Latin cross cut into the west door jamb next to the Holy Water stoup (Plates 5,6).

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

.

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

‘Shoe Outline’ Graffiti

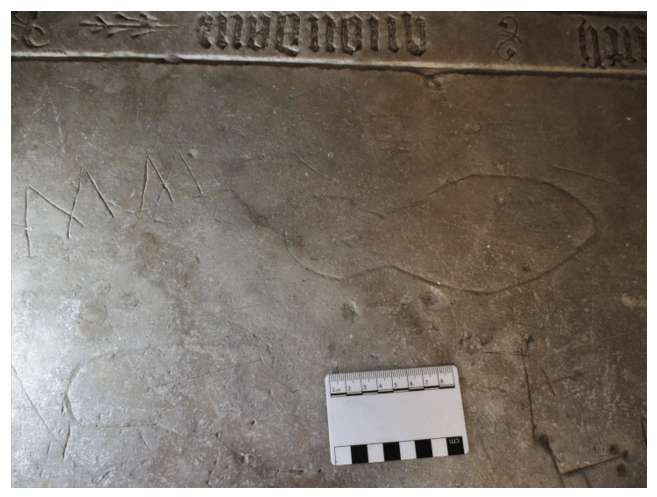

On the wall of the north aisle are two lead plates or plaques, bearing bas-relief figures and decorative flourishes. On closer inspection – and with the use of a raking light applied at 45o – two shoe-outlines were revealed which had been cut into the soft lead (Bull 2023, Vigar 2023) (plates 7, 8). It transpires that both lead plates had been removed from the tower roof in 1935 (Bull 2023) Local historian Christophe Bull recounts the local folklore that, ‘the footprints are believed to be those of William Brown of East Court Farm, a major mid-18th century landowner’ (Bull 2023). This is a believable premise, as often patrons of the church would be associated with the work and maintenance carried out on the building. This type of graffiti can therefore come under the category of ‘commemoration’ graffiti. The shoe outlines are considered to be the ‘signatures’ of the workers (or plombiers) which are then ‘confirmed’ by the addition of the vicar’s shoe outlines along with those of the verger and anyone else involved (Easton 2013:41).

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

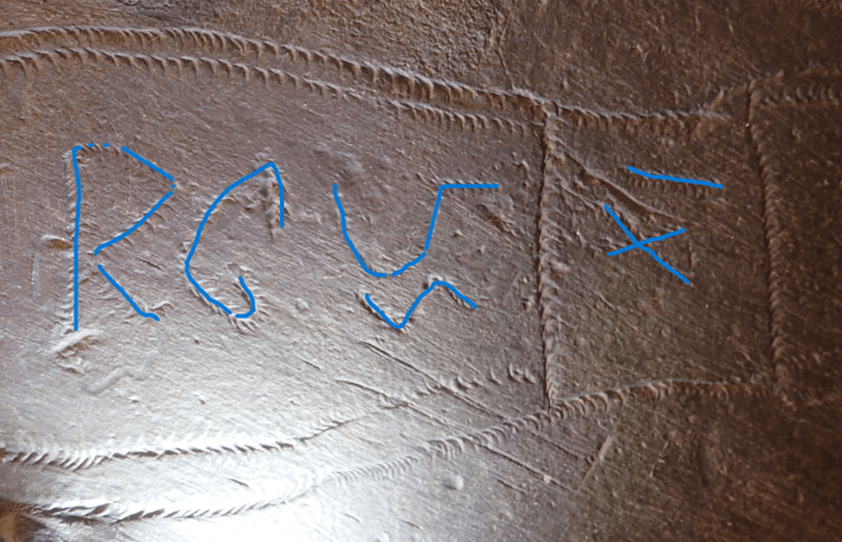

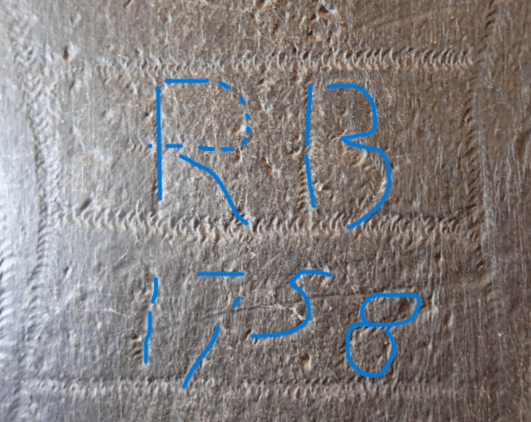

However, the two shoe outlines are of two different shoe types – one squared and one pointed shoe suggesting more than one person present. The dedications are also hard to read-I have tried to over-write them but they are incomplete and, like so much graffiti, a difficult to decipher. The pointed shoe seems to read, ‘R B 1758,’ the squared toe shoe appears to read, ‘RC…SG…XI / 8I (?) (Plates 9, 10). If I have read the date correctly, the making of the outlines would have occurred some time after the commemoration date on the second lead plaque. This plaque also has a small amount of graffiti including the letter ‘T’ cut below the initials W.N.

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

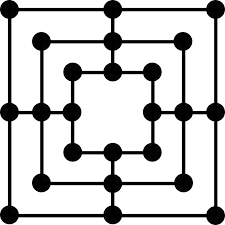

The phenomenon of shoe outlines is known from elsewhere and the technique employed to create the design – known as ‘wiggle’ work – describes the way a pointed metal object had been used to create the designs by moving the blade from side-to-side as the design was cut.

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

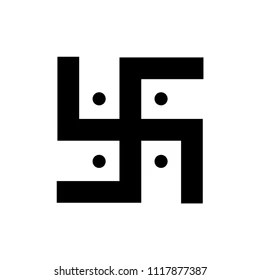

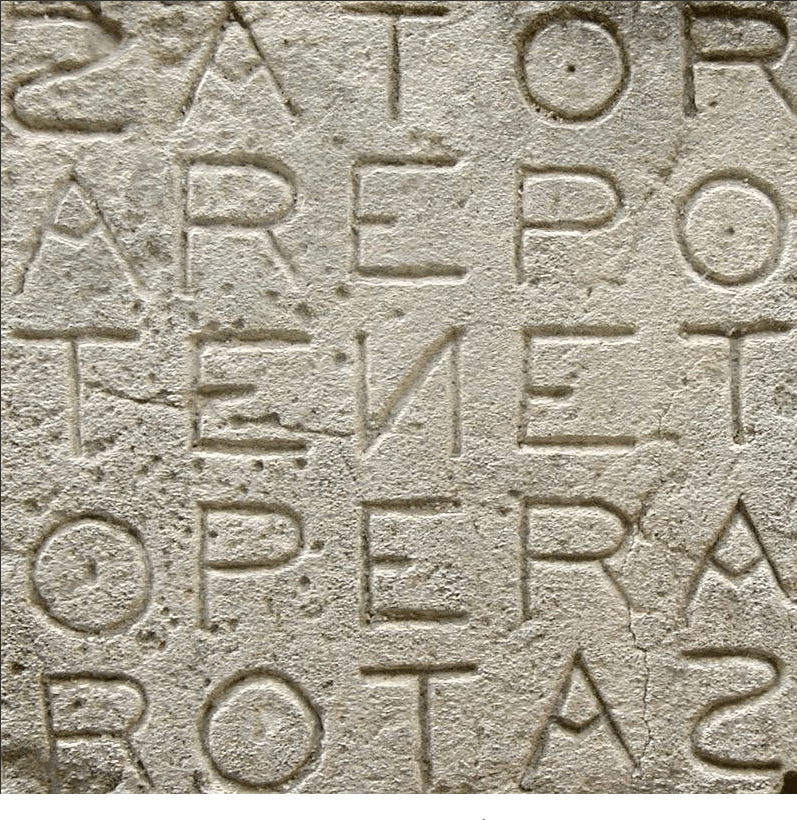

The lead panels are both hugely decorative and beautifully made by master craftsmen. Each possess two raised fleur-de-lis and lead-cut ‘flowers.’ The one with the shoe graffiti features three bas-relief figures -all of which appear to be female and are all holding babies or children. In Christian scared numerology, the number three invokes the protection of the Trinity. The magical associations of the number three and ‘triple deity’ iconography (representing the three stages of life) are known from Greek and Roman sculpture. The use of “triplism” in ancient iconography reflects a way of, ‘expressing the divine rather than presentation of specific god-types’ (Green 1999). In this scene, both the fleur-de-lis and possible roses (?) have Marian connotations. The figures clearly show the role of the Virgin as the protector of women in childbirth and her protection over pre-Baptised children who were considered particularly vulnerable.

Public domain: Wikicommons. Photo credit: Urban

In the study of medieval and historic graffiti, shoe outlines are considered to be one of the universal motifs that occur all over England and throughout history (Champion 2017). The shoes as an object themselves, (as opposed to the foot), appear to hold the significance, as many examples of shoe outlines, etched or cut into lead roofing, or carved onto masonry is a common phenomenon and has been recorded in many medieval graffiti studies (Swann 1996:3, Merrifield 1987: 136).

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

Outlines of actual feet are rare and early interpretations for this phenomenon suggested that they represented marks left by pilgrims visiting relics or shrines. However, this idea was debunked long ago, based upon the shoe style alone. The biggest giveaway, is that many carry initials and dates which are – for the most part – post-Reformation in date.

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

In some cases, the depiction of the soles of the shoes can show the division between sole and heel as well as hobnail patterns, some with the addition of apotropaic designs (Davidson 2017: 75). Other seem to show details relating to the cobblers art.

The largest corpora of shoe outline graffiti has been recovered from the lead roofs of churches. In the main, these ‘commemoration’ dates fall between the 17th and 19th centuries. The designs often contain initials (one presumes of the executor) and a date which are memorialising an event, it would seem to be of repair or re-roofing (Easton 2013: 40), (Champion 2017). In some instances, they can be found in great number which would have exceeded the number of plombiers (lead workers) required for the roofing. It is possible that the origins of the tradition can be traced back the clergy or congregation copying or adding to the initial assemblage created by the workmen (Easton 2013: 40).

These pragmatic explanations only cover a specific sub-category of shoe outlines but do not explain the image of the shoe or boot being used as an apotropaic device.

Photo: © W Perkins 2023

Apotropaic Boots & Shoes

Examples from the lead roof at Tannington, Suffolk displayed saltire crosses (often in threes – for the Trinity – and the saltire is a known ‘occlusive’ or ‘barrier’ symbol) as well as hearts and diamonds – all of which are known apotropaics. The addition of these symbols suggests there was a ritual process being adopted to their work (Easton 2013: 46). Workmen were superstitious and often ‘blessed’ their work – particularly when that work was on a religious establishment. Additionally, the location of the marks on the roof of the church (which was only accessible to a small select group of people) lends weight to the argument that many these ‘ritual’ practices required an element of secrecy or non-disclosure for them to be effective.

Photo: © W. Perkins 2019

Deliberately Concealed old Boots & Shoes in Ancient Buildings

The phenomena of deliberately concealed old, worn-out leather shoes and boots found within old buildings is now an attested practice acknowledged by archaeologists. It seems that the objects were believed to have acted as a prophylactic (a measure taken to fend off a disease and infestation of a building), to bring good luck or to ward against the evil eye and/or maleficium (malignant magic).

Concealed shoes have been found in building contexts – both religious and secular – from all over the English-speaking world and are widespread across Europe (Cameron 1998:2, WDOAM 2007:33, Hoggard 2017: 8). They were by far the commonest charm used to protect buildings in post-medieval times (Merrifield 1987: 131).

Photo: © W. Perkins 2022

Northampton Concealed Shoe Index

Reports of concealments are logged onto the Northampton Concealed Shoe Index (set up by June Swann from Northampton Museum) which has now recorded over 2000 examples from the British Isles, Western Europe, Switzerland, Germany the Czech Republic, Italy and Turkey and now there are numerous examples from North America and Australia (Swann 1996:1).

Photo: © W. Perkins 2022

Spatial Patterning

Although most shoe concealments follow the basic pattern of the object being lodged in a domestic chimney on the smoke shelf, concealed shoes have been found in farm houses, manor houses, palaces, chapels, churches, cathedrals, monasteries and synagogues. Shoe and clothing caches have been found in chimneys, under floors, above ceilings and sometimes guarding ‘danger’ points such as doors, windows and stairs. The chimney, fireplace and hearth as well as its inglenooks were a particular focus for concealments (Swann 1996:3). These could be described as being ‘peripheral’ locations separating sky from house, representing a zone of marginality or the transitional area between inside and outside (of a building) (Houlbrook 2017:63). Merrifield (1987: 128) believed that the placement of protective objects had always been focussed on the roof as that was where fires began, furthermore, the chimney was an important place to protect as it was believed to give ‘ready access to spirits.’

Photo: © W. Perkins 2020.

The shoe outlines at Chalk church hint at much wider connection with the phenomena of deliberately concealed shoes and the great swathe of shoe lore in general.

More on the above – with a whole wedge of shore lore – will be explored in my forthcoming talk for Viktor Wynd & The Last Tuesday Society –

Bibliography

Benton, J R (1997) Holy Terrors: Gargoyles On Medieval Buildings

https://archive.org/details/holyterrorsgargo00bent/page/n7/mode/2up

British History Online: Chalk

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-kent/vol3/pp457-471

[accessed 21 November 2023]

British Listed Buildings: St Mary the Virgin, Chalk, Kent

https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101089044-church-of-st-mary-gravesham-chalk-ward

Campbell, O (2021) Medieval Pilgrims Apparently Tried to Ward Off the Plague With Bawdy Badges: Metal phalluses and vulvas were thought to protect against disease.

Medieval Pilgrims Apparently Tried to Ward Off the Plague With Bawdy Badges – Atlas Obscura

Champion, M (2015) ‘Medieval Graffiti.’ Ebury Press, London

Champion, M (2017) ‘Medieval Graffiti Survey: Volunteer Handbook.’

Chapman, J & Smith, S (1981) Finds From a roman Well in Staines in, London Archaeologist 1981.

Davidson, H (2017) Holding the Sole: Shoes, Emotions & the Supernatural. PhD Thesis unpublished

Discover Gravesham (Gravesham Borough Council 2023) St Mary the Virgin, Chalk, Kent

https://www.discovergravesham.co.uk/chalk/st.-mary-the-virgin-chalk-parish-church.html

Easton, T (2013) ‘Plumbing A Spiritual World’ in, Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings Magazine. Winter 2013.

Hasted, E (1797) ‘Parishes: Chalk’, in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 3 (Canterbury, 1797), pp. 457-471.

Historic England: St Mary the Virgin, Chalk, Kent

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1089044?section=official-list-entry

Jones, M (203) The Secret Middle Ages: Discovering the Real Medieval World

Kent Past

https://www.kentpast.co.uk/chalk.html

Lionheart Replicas

Merrifield, R (1987) ‘The Archaeology of Ritual & Magic.’ BT Batsford Ltd, London

Green, M (1999) “Back to the Future: Resonances of the Past”, pp.56-57, in Gazin-Schwartz, Amy, and Holtorf, Cornelius (1999). Archaeology and Folklore. Routledge.

Rider, C (2020) ‘The Demonic Charm of Medieval Magic’ in, Medieval Magazine Spring 2020

Roof, J (2023) Apotropaic Genitalia

Swann, J (1996) ‘Shoes Concealed in Buildings’ in, Costume No.30 pp.56-69

Swann, J (1998) Hidden Shoes & Concealed Beliefs’ in, Archaeological Leather Group Newsletter, Issue 7 http://www.archleathgrp.org.uk/newsletter.htm

St. Mary the Virgin, Chalk

Torode, C (2023) Bawdy Badges, Lionheart Replicas

https://www.lionheartreplicas.co.uk/Bawdy-Badges.html

Torode, P (2019) Chalk Village: A Walk in Time.

Vigar, J (2023) Kent’s Churches: St Mary the Virgin, Chalk, Kent

https://www.kentchurches.info/church.asp?p=Chalk

Protecting Hearth & Home: Ox Row Inn, Salisbury Nov 2022.

St. Lawrence Church, Bourton-on-the-Hill has plenty of grafitti on the lead tower roof. Well worth a look if you can get the key from Church Warden.

LikeLike

Great tip-off Stephen, and to think, I’ve driven past that church between London and Worcestershire for about 40 years and never once suspected its secrets!

LikeLike