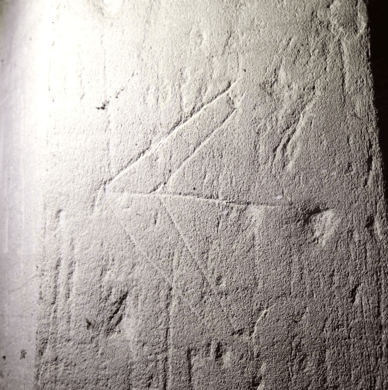

Main image: Fresco in the former Abbey of Saint-André-de-Lavaudieu, France. Anon.

Public domain Wikicommons

What might have been a suitable apotropaic to deploy when faced with the threat of plague during the later Medieval period? A Sebastian arrow amulet may have done the trick….or the representation of arrow cut into a wall…..

Arrow Graffiti

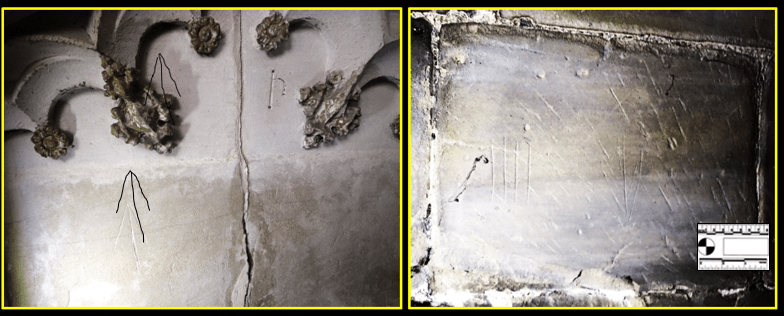

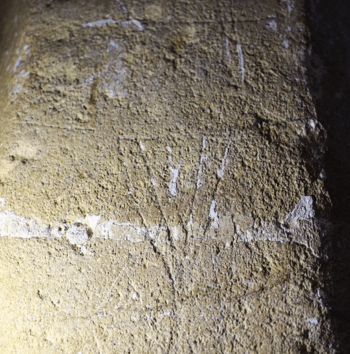

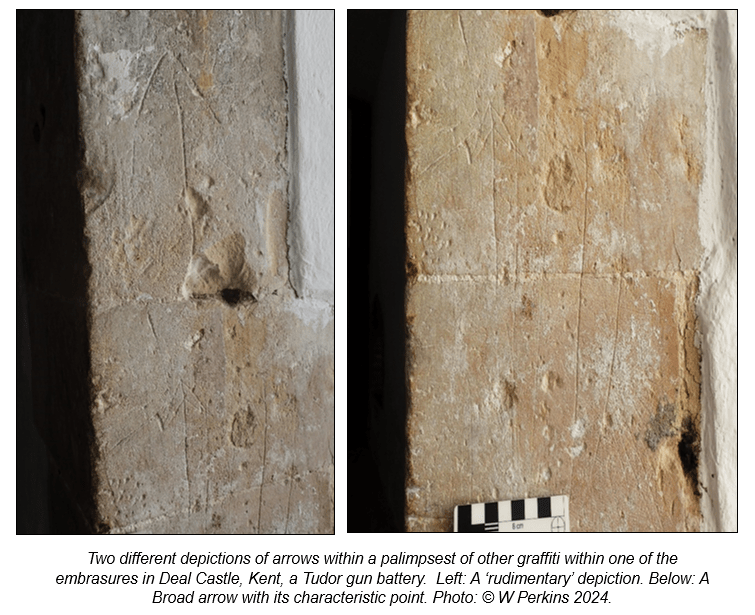

Arrow graffiti – rendered in its simplest form as three straight (or almost straight) lines converging on a point – has often been overlooked within the corpora of medieval graffiti. Firstly, they have often been misinterpreted; thought to be the ‘positioning’ marks made by the stone mason, (Ross-Wallace 2024); secondly, they have been interpreted as simply representing a physical arrow (presumably inspired by the belief that archery practise was once undertaken in the local churchyard) or thirdly, that, due to the often rudimentary rendering, they were considered of little import. However, there may be more to those little arrows everywhere…

Photo: © W Perkins 2023.

Photo: © W Perkins 2023

Medieval Archery Laws

Past interpretations for arrow graffiti have suggested that the marks were simply depicting a common-place, utilitarian object. Historically, local folklore held that archery had a close association with churchyards. This belief was itself supported by another slice of oft-repeated folklore that many of the vertical grooves found on the external masonry of buildings were the result of arrow ‘sharpening’ events having taken place.

Archery practice was mandated by the first Medieval Archery Law passed in 1252, when all Englishmen between the age of 15 to 60 years old were ordered to equip themselves, by law, with a bow and arrows. The Plantagenet King Edward III took this further and decreed the Archery Law in 1363 which commanded the obligatory practice of archery on Sundays and holidays which, “forbade, on pain of death, all sport that took up time better spent on war training especially archery practise” (Alchin, L 2017). However, this assumption has been addressed. Archaeologist James Wright has gone to some lengths to dispel the myth that archery practice took place in churchyards, for a variety of practical reasons. Archery practice was almost certainly confined to the Butts and the vertical faces of stone blocks make a poor sharpening surface (Wright 2021).

Photo: © W Perkins 2021

Photo: © W Perkins 2022

Photo: © W Perkins 2022

Coats of Arms & the Attributes of the Saints

Arrows featured heavily in heraldry, when they were frequently used as charges, either singly or tied in bundles or sheaves. The position / orientation of the arrow was important in the blazon. Frequently the points and feathers of the arrows were of a different tincture from the shaft. In such cases, the arrows are usually described as ‘barbed’ or ‘flighted’ but the expressions ‘armed’ and ‘feathered’ are occasionally employed (Brooke-Little 1996).

Photo: © W Perkins 2022

Arrows were sometimes deployed among the attributes of a martyred saint, including St Ursula, St Augustine of Hippo (5th century AD), St Edmund of East Anglia (9th century AD) and St Giles (8th century AD), the latter pierced with a golden arrow (Ellwood Post 1996).

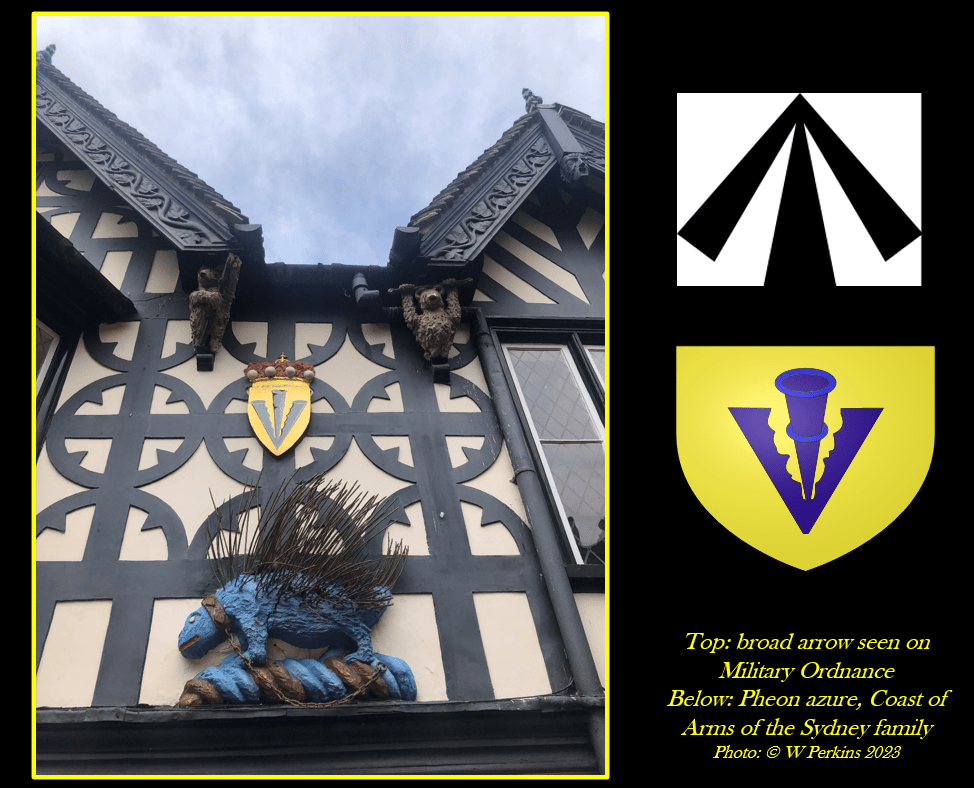

The Broad Arrow & Pheon

The Broad arrow – sometimes called a ‘broad head’ – appears in graffiti corpora as a stylised representation of the metal arrowhead. According to the Royal Armouries, broadheads were used in peacetime for hunting large game because of their ability to cause large, disabling wounds. In war, they were used against horses and unarmoured men (Royal Armouries 2024, Wadge 2008).

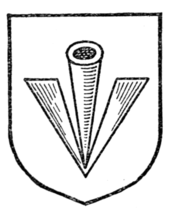

In heraldry, where arrows are frequently found, arrowheads and Pheons are of common usage (Fox-Davies & Charles 1909: 283). Their ordinary position is pale, that is to say, with the point facing downwards (falling: tombante) (James 1970: 23).

The Pheon is a broad arrow variant and was traditionally used in heraldry, notably in England (Seiyaku 2024). The broad arrow as a heraldic device comprises a socket tang with two converging blades, or barbs. When the barbs were depicted as ‘engrailed’ on their inner edges, the device may be termed a pheon (Woodward & Burnett 1892: 350), although this distinction is not always adhered to (Fox-Davies & Charles 1909: 283). The Pheon (or ‘pheon azure’) is perhaps most recognisable component of the coat of arms of the Sydney family of Penhurst. It is the relationship between the Sydney (later spelt Sidney) Family and two examples of the use of the broad arrow motif that has presented something of an enigma. In the past, the symbol has been deployed in both a pragmatic context and in one that could be interpreted as having an apotropaic function.

Military Ordnance

It is commonly believed that the stylised Broad Arrow symbol first appeared on British Military equipment in the 14th century but was more widely used from the 16th century onwards. Its appearance on British Ordnance sets up an interesting paradox, as its true origins remain obscure. Sir Philip Sidney was the Joint master-general of the Ordnance (1585-6) and Henry Sydney, 1st Earl of Romney was Master-General of the Ordnance (1683-1702) which seems, conclusively, to tie to the symbol and its use on military equipment. As stated above, the broad arrow variant, the pheon was part of the coat of arms of the Sydney family but the early use of the device predates the association of either Sidney / Sydney. The Broad Arrow Tower in the Tower of London dates from the 14th century and was connected to the government department responsible for royal supplies (again making a connection between ordnance and the broad arrow motif). Today, at the Tower of London, the Broad Arrow Tower has been re-presented as a guard tower, which was its original use (Historic Royal Palaces 2024).

Public domain, Wikicommons.

The Broad Arrow & the Shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham

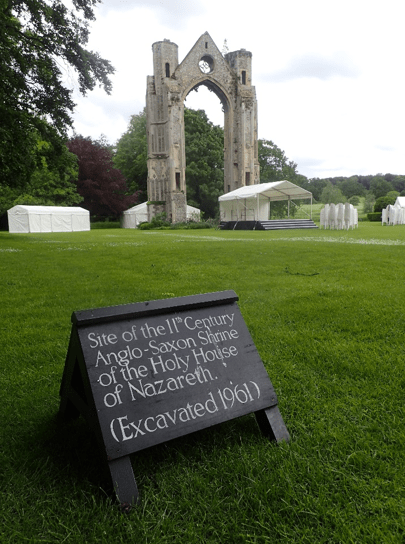

The combination of the broad arrow motif, wedded to a six-pointed star make up the insignia of the Walsingham Shrine and its origins are equally enigmatic. The Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham was the second most popular site of pilgrimage in England after Thomas Becket’s at Canterbury after it was established in the early 12th century.

Photo: © W Perkins 2024

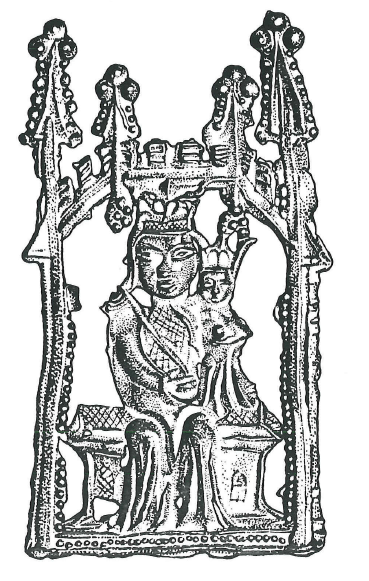

In brief, the Walsingham legend tells of a pious Saxon Noblewoman called Richeldis de Faverches, who prayed to Our Lady and asked as to how she could honour her. During a religious ‘ecstasy’ a vision of the Virgin appeared and led Richeldis’ spirit to Nazareth. Here she viewed the ‘holy house’ – the building where the Archangel Gabriel had appeared to Mary during the Annunciation. Observing the house, the Virgin bade Richeldis to, ‘take measurements’ and to re-build it at Walsingham. Even though there is still some debate regarding the date of its inception, it is generally agreed that the structure – housing an effigy of the Virgin – was established around 1061 and soon became the focus of veneration and miracles. It was primarily this miracle-working image that transformed Walsingham from an obscure hamlet into a place of national interest and importance (Spencer 1980:10).

Photo: © B Spencer / Norfolk Museums Service 1980

A second legend relays the story that during the night prior to the construction of the Holy House there was a heavy fall of dew but in one meadow two spaces of equal size remained dry. Richeldis took this as a sign and chose the plot close behind a pair of twin wells. Apparently, the prototype Nazareth also possessed the same associations with a well, the water of which being noted for its miraculous healing properties. The associations with ‘holy’ wells or springs are a regular feature of sacred sites and there can be little doubt that Walsingham’ s pilgrims took away ampullae or miniature flasks containing this beneficial liquid (Spencer 1980: 16).

The builders awoke the next day only to find the Holy House fully completed but this time it had been moved to the second spot. It was concluded that this miracle could have only been effected by the Virgin herself, who had chosen the favoured spot for the chapel (Walsingham Village 2024).

The Shrine and surrounding complex were eventually curated and manged by the Augustinian Canons who enshrined it in a chapel within a much larger church (Walsingham Village, Community of Walsingham, Walsingham Anglican 2024). From Henry III onwards, nearly every king and queen visited the site and, alone among English shrines, it was still drawing crowds of pilgrims at the time of the Reformation (Spencer 1980). It has been mooted that the original statue of the Virgin somehow survived the Dissolution after having been taken to Lambeth and can be seen today in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (Michael 2019). This is, however, still open to debate.

The Shrine was dismantled during the Dissolution as a result of the Suppression of the Religious Houses Act of 1535. In 1538 the Suppression of the Priory was supervised by Sir Roger Townshend. Immediately after its dissolution the site was acquired by Thomas Sidney, master of the hospital of Little Walsingham, for the sum of £90 (HE 2024). Thomas was the son of Sir William Sidney IV whose family had adopted the ‘pheon azure’ and chained porcupine into their coat of arms (NA 2024).

Pilgrim Souvenirs

No-one had studied pilgrim badges more thoroughly than Brian Spencer and in ‘Medieval Pilgrim Badges from Norfolk’ (1980) he explained their significance, ‘The leaden souvenirs usually took the form of hat-badges and were cast in tens of thousands every year at the larger pilgrim-centres. Trade in them served many ends. It brought revenue and gratuitous advertising to the churches involved in it and a livelihood to nearby craftsmen and shopkeepers. It provided the pilgrim with eye-catching proof of an accomplished pilgrimage and visible passports that helped ease his journeys. More important still, perhaps, the badges themselves, from their association with holy places, were generally thought of as secondary relics that exercised their own powerful magic and were therefore to be cherished or passed on to someone in need of saintly help or protection.’

Spencer thought that it was likely that Walsingham Priory had possessed its own workshop from which a number of variations on the Shrine theme were manufactured. These included those badges of a seated Lady of Walsingham (based upon the original statue), simpler versions in rectangular or round frames and one which depict the scene of the Annunciation. Some take the form of Hunting Horns (containing the Virgin’s milk) and some the Holy House itself, as the structure was considered to be, ‘..of exceptional importance’ (Spencer 1980: 11).

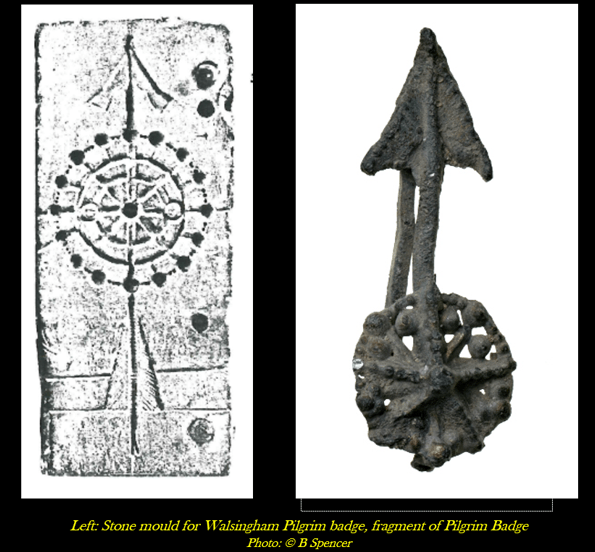

One of the pilgrim badges from Walsingham held by the Museum of London is composed of a six-sided star mounted on an arrow shaft. It is dated to the 15th century, clearly linking the Broad arrow to the Shrine at Walsingham. However, documents seem to suggest that the Sydney/Sidney family did not become involved with the site until its demolition mid-16th century. Where the Broad Arrow is associated with both the British Military Ordnance and the Walsingham Shrine, both had close associations with the Sydney/Sidney family – even if the use of the symbol appears to have predated the Sydney Family’s involvement.

The badges which had incorporated the Broad arrow, however, are similarly enigmatic. A stone mould (No.30) of Lithographic limestone imported from Solnhofen, Bavaria bears a six-pointed star with trefoils between each point. It was used to casting five badges and dates to the 15th century (Spencer 1980: 14). Its reverse depicts two more identical six-sided stars incorporated into the shaft of two arrows which are notched, feathered and fitted with a broad, barbed head. Spencer concluded that, although the arrow device featured prominently on several badges (and ampullae) from Walsingham, its inclusion was still somewhat ‘enigmatic’ (Spencer 19180: 15). On another mould (no.35), Spencer describes the star on the shaft of the arrow as resembling a, ‘target or mariner’s compass’ (Spencer 19180: 15).

Plague Arrows

Whilst placing the pragmatic interpretation of the arrow motif as an item of weaponry to one side for the moment, it is possible that it may have embodied more significant, symbolic connotations for the maker. In ancient times, the common metaphor used for the plague was the arrow. It was not seen merely as a depiction of a weapon but was a form traditionally invoked to represent a carrier of disease, especially the plague (Hall 1989, Newhouse 2015). At some point in the past, the metaphor for a hail of plague arrows was understood as a sign of divine displeasure and one which has been employed since ancient times (Katz 2006). When utilised in symbolic art, Medieval arrows are never ambiguous: they represent force and violent death in general, and martyrdom in particular (Daeseger 2024).

Medieval Symbolism

By the Middle Ages, there had evolved a variety of explanations for the causes of the plague and a number of metaphors were used to denote those causes. An iconography for the plague was developed, including the imagery and the symbolic language to represent it (Berger 2008).

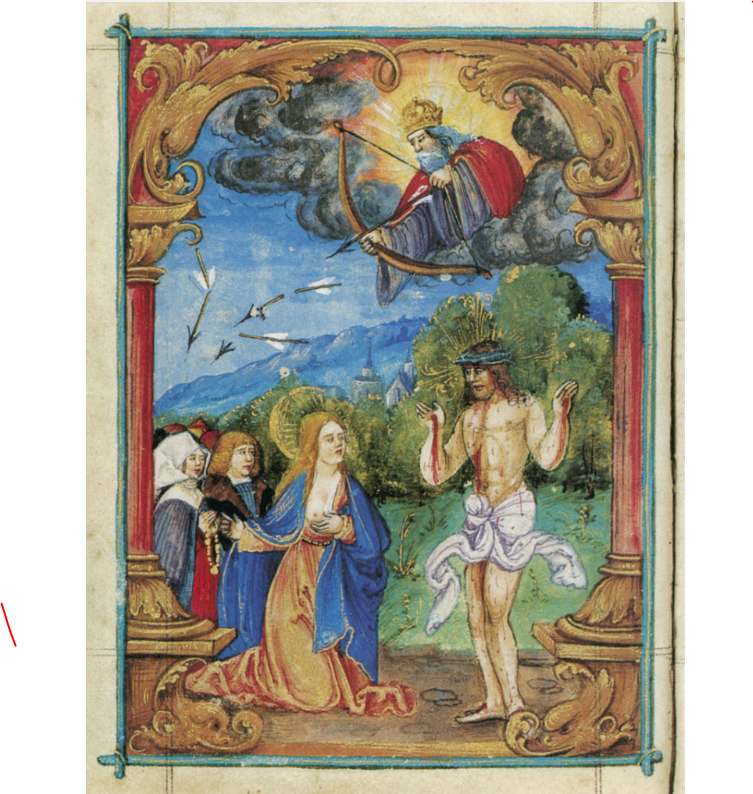

Reproduction © Commonwealth Magazine 2020

It was believed that the arrows of God’s wrath could hit the young and old, the weak and strong, saint and sinner equally and without favour. While one could reason that the relatively small number whom God smote with leprosy may have merited the disease for sinful or moral reasons, plague visited everyone (Newhouse 2015). In 1533, Andreas Osiander argued that both the pious and evil die during plague. For the sinful, it was the wrath of God; for the righteous, it was simply their time (Newhouse 2015).

Near East & the Mediterranean World

The idea of the raging plague in the form of arrows bringing disease was not only a ‘symbolic’ metaphor for how pathogens spread but also a classical interpretation of this world: the idea of an arrow shot by a divine archer as a carrier of the infection was not just common to the early Greek thinking of the Homeric world (Sandberg 2024). Those deities that had visited a plague of arrows upon people included Reshef (a Syrian-Palestinian deity), The Hittite God Jari, Mesopotamia’s Nergal and the Egyptian Sekhmet. However, perhaps the most relevant antecedent to the medieval world’ s metaphorical use of the arrow as plague carrier was the Olympian Apollo (Sandberg 2024).

Reproduction © The Society 2021

Later Medieval Era; the Black Death

In the later medieval era, perhaps the most dramatic expression of this motif is a fourteenth-century fresco on the wall of the former Benedictine Abbey of Saint-André-de-Lavauadieu in France. It depicts the plague personified as a blank-faced, hooded individual, who carries arrows which strike those around it. The arrows are seen to have found their targets – often in their necks and armpits—in other words, places where the buboes of the Black Death commonly appeared (Daeseger 2024).

Public domain Wikicommons

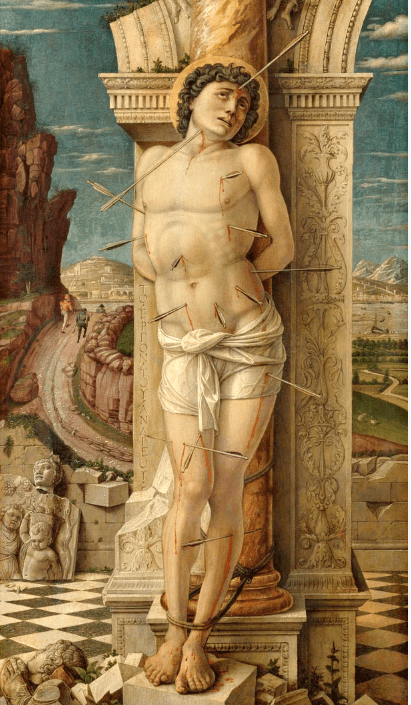

In the later medieval era, St Sebastian emerged as the most popular ‘plague’ saint, as the arrow came to symbolize the plague itself. St. Sebastian was a captain in the Praetorian Guard until he was denounced as a Christian. After learning that there was a Christian in his bodyguard, the Emperor Diocletian ordered his execution. Sebastian was tied to a tree (sometimes depicted as a column) and was to be executed by archers. However, when the pious widow Irene finally went to remove his body, the miracle revealed itself to her: peppered with arrows, Sebastian still lived (Sandberg 2024).

Public domain, Wikicommons. Reproduction © Kunsthistorisches Museum

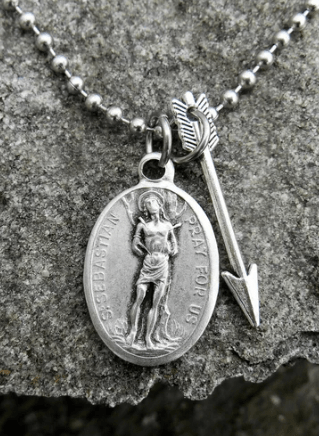

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger; pilgrims took to wearing St Sebastian amulets.

His role as an intercessor against plague can be dated to c.680 common era, when he was credited with saving what was believed to have been his hometown of Pavia from a virulent epidemic (Katz 2006). Following this, he was often prayed to for protection against the plague. Sebastian had been both venerated for many centuries prior to his assuming the role of a protector against plague. His cult originated sometime before AD 354 at his tomb in the catacombs on the Via Appia in Rome. It quickly flourished thanks to the stream of pilgrims to a basilica that was built above these catacombs in the late fourth century, originally called the Ecclesia Apostolorum (Barker 2008).

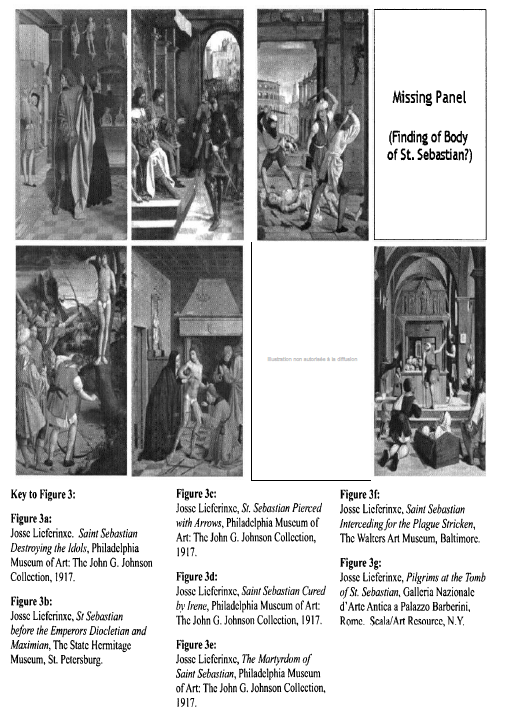

In 15th century Provence, an altarpiece was dedicated to Saint Sebastian containing a unique iconographical representation of the culture of affliction, adversity, and destitution. It was created by Josse Lieferinxe (alias the Master of St. Sebastian), between 1497-99 for the church of Notre-Dame-des-Accoules in Marseilles. The Retable Altar of Saint Sebastian depicts multiple acts of healing in a conscious display of therapeutic art and practice and has been the object of study by M R Katz in 2006. By examining the monument in relation to the medical, civic, and spiritual milieu of the region in the last quarter of the 15th century, the author was able to support an apotropaic reading for the altarpiece, dedicated to the patron saint most frequently invoked as an intercessor against the plague, St Sebastian.

Galleria Nazionale d’ Arte Antica, Rome

Afterword

This exploratory article has tried to offer an alternative reading for the arrow motif which regularly occurs in surveys of medieval graffiti. I have outlined the way in which, in past societies, the metaphorical link between the ‘random’ deaths meted out by arrow fire and the apparently ‘senseless’ deaths from diseases developed in the ancient world. The evidence suggests that the was metaphor of ‘arrow as carrier of disease’ was adopted by both the Classical and Mediterranean worlds through long-term connections and cultural transmission. If it can be said that different belief systems show at least some elements of syncretism then, perhaps too, some of the innate qualities of the gods were absorbed too. On the battlefield, great volleys of arrows appeared to find their marks as if by random. This apparently chance outcome had to be understood and reconciled in some way. By creating a God whose attributes included pestilence and disease, then one would have been given a fighting chance of placating them through offerings and suitable prayer. It is no mystery then that this metaphor should have arrived fully formed into the medieval world and was subsequently used as way of coming to terms with ‘random’ misfortune. Additionally, the depiction and adoption of the arrow symbol was a way of countering the threat of plague by re-casting it as an apotropaic device.

Wayne Perkins

(BA, ACIfA)

London August 2024

Bibliography

Alchin, L (2017) The Butts

https://www.lordsandladies.org/the-butts.htm

Barker, S (2008) ‘The Making of a Plague Saint Sebastian’s Imagery and Cult before the counter-Reformation’ in, Mormando & Worcester (Eds). Volume 78, Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies

Berger, P (2008) ‘Mice, Arrows, and Tumours in Medieval Plague Iconography North Of The Alps’ in, Mormando & Worcester (Eds). Volume 78, Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies

Broad Arrow

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broad_arrow

Brooke-Little, J P (1996) A Heraldic Alphabet. Bolsover Books, London.

Daseger (2019) Steets of Salem: Allegorical Arrows

Ellwood-Post, W (1998) Saints, Signs & Symbols. SPCK Publishing.

Hall, J (1989) Hall’s Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art.

Historic England (2024) Ruins and site of Walsingham Priory, Walsingham Abbey, Walsingham, Norfolk

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1004055?section=official-list-entry

Katz, M R. ‘Preventative Medicine: Josse Lieferinxe’s Retable Altar of St. Sebastian as a Defence Against Plague in 15th Century Provence.’ In: Interfaces. Image-Texte-Language 26, 2006. Representation of Illness in Literature and the Arts/Maladie : Représentations dans la littérature et dans les arts visuels. pp. 59-82;

https://www.persee.fr/doc/inter_1164-6225_2006_num_26_1_1311

Michael, M (2019) Original Our Lady of Walsingham Statue May Be in London’s V & A

National Archives (2024) William Sidney

https://www.geni.com/people/William-Sidney-MP/6000000001299345418

Newhouse, A (2015) Civic Belonging and Contagious Disease In Sixteenth-Century Nuremberg

Parker, J (1970) A glossary of terms used in heraldry: Arrow. Harvard University p.23

Sandberg, M (2024) Of Plague Arrows & Miracles – of Gods & Saints

Spencer, B (1980) Medieval Pilgrim Badges from Norfolk. Norfolk Museums Service 1980

Stuart-Jones (2024) ‘The Memoria Apostolorum On The Via Appia,’ in, Journal of Theological Studies

Tower Of London (2024) East Battlements, Broad Arrow Tower

https://www.hrp.org.uk/tower-of-london/whats-on/battlements/

Walsingham Village

Wintre (2024) St Sebastian: Arrows & The Virgin

Wright, J (2021) Mediaeval Mythbusting Blog #10: Arrow Stones

Wadge, R (2008) ‘Medieval Arrowheads from Oxfordshire’ in, Oxoniensia. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. p.10.

Woodward J & Burnett, G (1896) A treatise on heraldry British and foreign: with English and French glossaries

Online Resources

A Guide to Christian Iconography: Images, Symbols, and Texts

https://www.christianiconography.info/conques/tympanum.htm

BAJR Guide 58: Guide to recording Stonemasons’ Marks

http://www.bajr.org/BAJRGuides/58_MasonsMarks/58_RecordingMasonsMarks.pdf

Black death (black plague fresco from 1355) St-André Abbey church, Lavaudieu

Broad Arrow Pilgrim Badge

https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/28959.html

Commonwealth Magazine

https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/act-service

Encyclopedia.com: Reshef

https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/reshef

Grex Luporum ( 2017) Medieval Arrowheads Database

Historic England: Church of St Margaret, Church Walks, Stoke Golding, Leicestershire.

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1074214?section=official-list-entry

Royal Armouries: Broadhead Arrows

https://royalarmouries.org/leeds

Secret Images: St. Sebastian (1457-59) by Andrea Mantegna

Society of Classical poets

Fresco in the former Abbey of Saint-André-de-Lavaudieu, France

Web Gallery of Art

Thanks Wayne. Just wondered if/how you can ‘date’ many of the marks? The arrow pictured at St. Giles, Bredon looks really recent. Do you ‘date’ them by their ‘style’, or is there any other method? Cheers, Brad

LikeLike

Hi Brad, dating graffiti is really difficult and often it is only possible to give a broad window of dates for its creation. The St Giles example was an enhanced version-I’ve now added the original photo so that you can see how feint it is in comparison! Each of the examples have a residue of white limewash paint/plaster in them suggesting they are older (Medieval?) examples. It is not always clear in the photos but each mark has been examined with a magnifying glass on the day! So, the majority were made AFTER the block was cut (terminus post quem) but BEFORE limewash as added (terminus ante quem) suggesting they may be dated between the 12/13th century to the 16th/17th century.

LikeLike

Thanks Wayne.

LikeLike

This would have been useful during COVID. I performed all manner of rituals in 2020 to stave off the tide of Covid. A group of friends would read the updates I put on the blog so that wherever in the world they were, they could perform the rituals and offerings I was doing as a collective deterrent to our modern plague. In the end, the spirits I work with here had me create a two part charm to ward it off :

1) A weird feather charm to ward off the spirit of death itself. To actually target death and destroy it with life.

And

2) A serpent Staff of Zeus I own

It’s a simple branch of a tree that I dedicated to Zeus. But in the Bible, Moshe (Moses) used a magical bronze serpent that was wrapped around his staff, as a magical charm to remove the spirit of disease.

I obviously can’t say that scientifically speaking it worked. I have no evidence. What I can say is this : Florida was the very worst place in the US for the disease. Because the Governor here cared more about commerce than he did human lives. At some point there was a scandal where the rotten corpses of Covid infected bodies at a funeral home were releasing corpse fumes near apartment buildings. And the numbers of deaths were far higher than reported. But he had his underlings change the numbers of deaths on the official website so that he could justify removing the restrictions.

So Covid was everywhere.

And yet somehow, despite the fact that I lived in a neighborhood full of idiotic Trumpers. Who didn’t respect social distancing. Who didn’t wear masks. The disease never made its way to where we lived.

I had created the same feather charms and placed them in strategic locations around the neighborhood. And I also anointed the street lights and anything else that could more or less pass as a “serpent” so that they could ward off disease. I should also mention my mother is a nurse who worked with a greedy doctor that wanted to keep going to infected places to make money.

With no regard for his own family. Yet somehow, we never got sick. And death seemed to get away from us. So I leave it with you to make judgement on whether or not it worked.

– M

LikeLike