Gatehouse to Baddesley Clinton Hall, a number of apotropaic marks can be found on the walls of the entrance passage. Photo: (c) W Perkins 2024.

One of the many ritual taper burn marks found in the house. Note that the ‘key’ marks made into the timber to receive plaster or render cut through the burn mark, which means that it was added to the timber earlier in the house’s construction. Photo: (c) W Perkins 2024

Further to my recent article, ‘Baddesley Clinton Hall: The Deployment of Apotropaics in an Elite Residence,’ new documentation has since come to light. I have been given access to the Building Survey by Bob Meeson, Nat Alcock and Dan Miles which was undertaken for the National Trust in 2002. The report, ‘Baddesley Clinton Warwickshire: Historic Building Analysis’ included the results of the visual and architectural survey itself, including beautifully hand-drawn elevations and plans, dendrochronology results from the key timbers and a background history detailing the owners of the site over time (Meeson et al 2002).

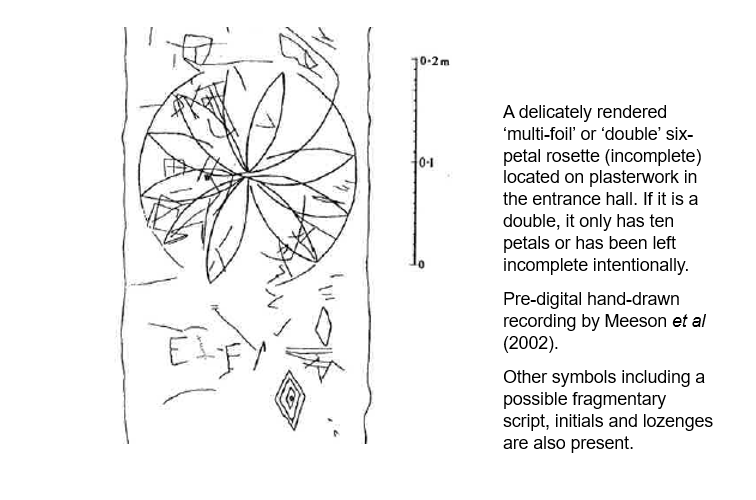

Multifoil, Entrance Hall

Also of interest are a number of other apotropaic marks which they discovered during the survey. Meeson had been aware of Timothy Easton’s article, ‘Ritual Marks on Timber,’ which had been published in the SPAB magazine in 1999. Therefore, when undertaking the survey he understood the significance of the symbols that he had encountered. He apportioned Appendix 3 of the report to the subject. He was also able to give an approximate date for their addition to the building fabric.

‘Increasing numbers of ritual marks are being found inscribed on timber, especially in the vicinity of doorways, windows and fireplaces, but the most impressive marks at Baddesley Clinton are inscribed into plaster and this might account for their unusually elaborate form. They are located in the entrance hall, in the plaster panel on the left side of the doorway which leads on into the Great Hall. Significantly, for much of its life this wall was covered by lath and plaster not only did this protect these fragile and normally vulnerable scratch-marks, but it also suggests that they were inscribed by or before the mid-eighteenth century.

Three of the symbols read as an elaborate set of intersecting Vs, or possibly Vs and Ms, and their general character suggests that an Elizabethan hand was responsible. Significantly, the tree-ring felling date for one of the timbers in this wall is Spring 1576 and the latest felling date for any timber in the building is Winter 1577-78. From the known construction date of the building and the general character of the marks, they are almost certainly sixteenth-century’ (Meeson et al 2002).

The multifoil found in the entrance hall is a variant of the six-petal rosette (more commonly referred to as a daisy wheel) and most researchers consider the motif to have possessed an apotropaic function. It was not possible to say if the motif had been executed as a multifoil or, if one six-petal rosette had been superimposed over another one to create the multifoil. However, it possesses only ten of its twelve ‘petals.’

Easton had also noticed how many examples of the compass drawn circles that he had encountered were incomplete – perhaps left intentionally so. If the use of the circle had been meant to represent Heaven, Eternity and Perfection, he mused, perhaps the circle had been left intentionally unfinished, so as to not presume upon God’s ‘perfection’ itself. The best analogy is the Japanese philosophy of ‘wabi-sabi,’ whereby one actively sees the beauty in imperfection and and embraces an appreciation of the incomplete .1

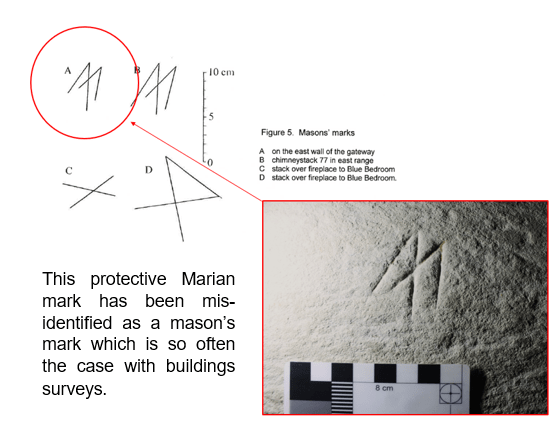

Marian Mark: East Wall of Gateway

In the survey, Meeson included this ‘particular’M’ (or conjoined VV) as a mason’s mark rather than interpreting it as an apotropaic. However, given the corpus of ritual protection marks within the building, I believe that it is far more likely that it was intended as an apotropaic, added to ‘guard’ the entrance passage to the building.

It is possible that, in the past, a mason may have ‘adopted’ a Marian mark as his professional mark. However, here at Baddesley we have all the usual issues when it comes to identifying ‘true’ mason’s marks. The problem, as ever, is the inconsistency of the markings on the masonry blocks. To make a real case for them being a mason’s mark requires a series of caveats to explain their absence elsewhere. Only a tiny proportion of the stones have a mark; it has been suggested in the past that the ‘missing’ marks are explained as having been weathered out; or perhaps the marks had been made on the reverse of the stone; or that the stones themselves had been ‘turned’ for some reason..etc etc. These explanations are not justification for calling one of the motifs a ‘mason’s mark’ when placed alongside the other evidence.

Noting the wide date range of the masonry components upon which the same mark occurred had made Meeson himself suspicious,

‘It has been suggested that a mason’s son could inherit his father’s mark, but it seems too much of a coincidence that the same mason or his son would be working at Baddesley Clinton in or before 1535, then again about forty years later, when the north range was remodelled.’ (Meeson et al 2002).

The Marian Mark was first categorised as an apotropaic by Timothy Easton as the result of a series of archaeological building surveys that he had undertaken in Suffolk, in the east of England. He was the first researcher to notice the mark which had been repeatedly cut into the timbers of the 16th-17th century buildings in that county. His meticulous recording of the structural timbers in the buildings revealed a patterning of repeating ‘V’ marks – often overlapping (or ‘conjoined’) – that had been cut into the wood with a carpenters’ rase knife. His short article, ‘Ritual Marks on Historic Timber’ in the Weald & Downland Magazine of 1999 was further bolstered by an addendum in the same issue by timber-framed building expert Richard Harris who, once alerted, found the same marks on the interior wall plates of a Drying Shed that he was reconstructing (Easton, Harris 1999: 22-29)

Easton’s corpora was recorded from both residential houses and farm buildings which held livestock, whilst those of Harris’ were from a building associated with the industrial process of drying bricks and tiles (Easton, Harris 1999: 22-29). It appeared that the marks had been intended to protect the tenants, the ‘things’ being fabricated – or, indeed, the processes being undertaken in those buildings which would have benefited from being ‘blessed.’ 2

Ritual Taper Burn Marks

In the previous article, I detailed the high quantity of ritual taper burn marks in the Moat Room. One horizontal timber had been removed or replaced, rendering some of the marks to appear ‘up-side down.’ Although Meeson did not have access to the latest archaeological thinking on their purpose and creation, his meticulous survey still manged to record the marks on a number of timbers not visible to the casual visitor. In my article, ‘Incendiary Behaviour’ I have charted the evolution of the study into the phenomenon and presented several case studies undertaken by different archaeologists in a range of ancient buildings.3

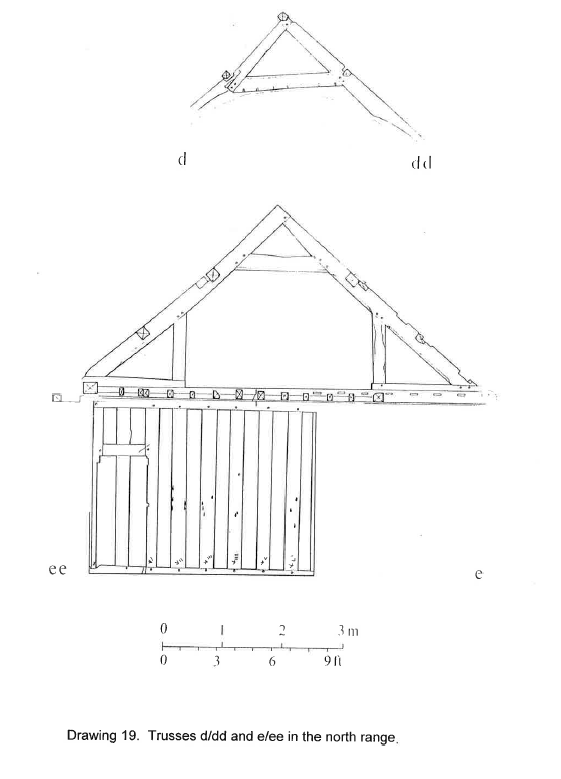

Detail of the truss drawings from the north range, the burn marks have been carefully drawn by Meeson’s team with the Roman numerals of the carpenters at the base of the studs (Meeson et al 2002).

Ritual taper burn marks in the Moat Room. Photo © W Perkins 2024.

The corpus of marks culled from the survey of Baddesley Clinton has returned evidence for a number of different apotropaic devices having been used throughout the building, with an approximate date for their application being between the 16-17th centuries.

Some of the ritual taper burn marks show knife cuts where the charcoal was scoured out of the hollow during burning, as in this example. Phot: (c) W Perkins 2024.

So far, the surveys have recorded –

- Marian Marks (entrance passage & internal fireplace)

- Compass drawn circles (including concentric ones, entrance passage)

- A multifoil (or double six-petal rosette, sometimes called a daisy wheel, entrance hall)

- Votive cross (above principal entrance)

- Ritual taper burn marks (in many locations, concentration in the Moat Room)

- An unusual, motif composed of ‘radiating’ lines in a ‘star’ pattern, located below a signature cut into the plaster (Moat Room)

It is a vivid example of the way in which a range of apotropaic symbols – and protective measures – were brought into secular buildings by the rising elite during the Early Modern Period.

© W Perkins February 2025.

Notes.

- Perkins, W (2022) Return to the Source. RPM website online article.

Kempton, B (2018) Japanese Wisdom for a Perfectly Imperfect Life. Piatkus.

- Easton, T (1999) ‘Ritual Marks on Historic Timber’ in, Weald & Downland Magazine. Spring Edition. p.22-28.

- Perkins, W (2002) Incendiary Behaviour. RPM website online article.

Links

1 Comment