‘Rattle his bones over the stones,

He’s only a pauper who nobody owns’

Well known ditty or saying (19th century?) quoted in T Lacquer 1983

A strange grouping of headstones can be found in the chapel cemetery which once belonged to Bordesley Abbey in Worcestershire. Many have initials and dates cut into what appears to be architectural masonry ransacked from the ruins of the abbey following its Dissolution. The memorials are reminiscent of the graffiti versions often found incised into the walls of England’s churches. Additionally, some of the old stones display shoe outline graffiti which is unusual in this context. Finally, is this the only archaeological excavation ever to have been haunted by a supernatural visitor?

Memorial Graffiti

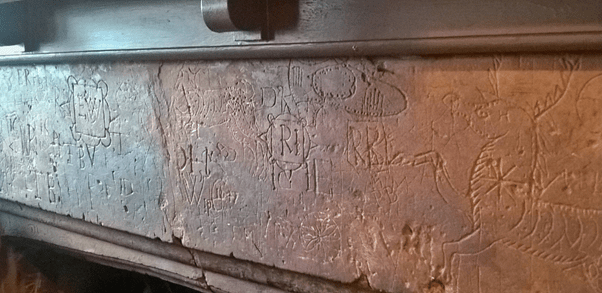

Examples of paired initials combined with a date is one of the commonest types of post-Reformation graffiti recorded during the surveys of ecclesiastical buildings. Often enclosed within a cartouche or rectangle they can range from the simple to complex; from the poorly executed to the elaborate. In some cases, the initials are contained within what appears to be a ‘building,’ complete with roof tiles and flowing pennants. They have been interpreted as examples of memorial graffiti and the earliest examples recorded so far date to the mid- 16th century (Champion 2015:202). This interpretation has found a general acceptance among academics but, as yet, there have been no examples which illustrate a direct correlation between the graffiti memorials and headstones erected in cemeteries. However, a number of crudely incised grave markers located in an often over looked cemetery in the grounds of Bordesley Abbey in the Midlands may provide that link.

Plate 2: Even 15th century wall paintings were not immune from graffitists. In this instance, there may even be a suggestion that the initials ‘I/J R’ had been added intentionally, as the perpetrator may have viewed the ennobled figure of John Wooton as being a worthy intercessor for the deceased individual. Photo © W Perkins 2023.

It is logical to assume that, whilst society’s elite could afford grand funerary monuments as reminders to the public of their benevolence and achievements, the poor of the congregation may have been reduced to simple graffito dedications. In graffiti corpora, the motifs can be found as isolated examples but often aggregate into small groups. In fact, it was their similarity to headstones which suggested that the small plaques were meant as monuments to the dead, ‘looking like gravestones carved into the walls.’ (Champion 2015: 203).

With this as the working hypothesis, it should then have been simplicity itself to correlate the initials in the memorials with the parish burial records of the church. Paradoxically, the majority of graffiti examples cannot be matched to the church records (Champion 2015: 203). Therefore, although the interpretation appears sound, there is still an element of mystery surrounding this lack of correlation between the graffito as recorded and existing documents. Further, few of the recorded memorials use the visual conventions or devices deployed on the headstones of the period.

Plate 3: A series of post-Reformation memorials cut into the window jamb of the porch at St Margaret’s church Barming, Kent.

Photo © W Perkins 2023

Archaeologist Matthew Champion (2015: 209-10) has cited two dedications that were less enigmatic than the simple versions, as they used an extended text for the dedication, rather than the simple initials and date;

‘JF died the forst day of februaray 1708’

Stansfield church, Suffolk

‘JL Wiseman departed life, June 15th 1811’

Lidgate church, Suffolk

These are quite clear in their intention and motivation.

In the parish church of Bishampton, Worcestershire, much of the original fabric has been lost to the over-enthusiastic Victorian restoration undertaken by Frederick Preedy in 1870, when both the nave and chancel were rebuilt (W&DHC 2022, Historic England 2025). Luckily, this did not reach as far as the interior of the 15th century tower, where there are a number of similar dedications that are also not ambivalent as to their purpose, examples being;

‘T ShelDon DiED. Feb 2’

‘Ms Ford

DIED 11 DEC’

‘IY 1798’

Plate 4: Informal memorials, church of St James, Bishampton, Worcestershire. Photo: © W Perkins 2022.

A Pauper’s Funeral

It might worth asking, therefore, if the inscriptions we see are essentially the graffiti equivalent of interment in a pauper’s grave or suffering the indignity of a pauper’s funeral. Post-Reformation, pauper’s funerals were seen as a sign of social failure which would have been degrading to both the deceased and to their survivors. To be ‘put away on the parish’ could have led to life-long stigma for the family (Laqueur 1983: 109). In this period, funerary ritual was one where social standing was articulated through displays of acquired attributes like wealth, membership in organisations, philanthropic and entrepreneurial prominence. All of these indicators are evidently lacking from these simple graffiti inscriptions.

Bordesley Abbey & St Stephen’s Chapel

What then are we to make of the memorials to be found on the headstones in the often overlooked graveyard of the former St Stephen’s chapel within the grounds of Bordesley Abbey?

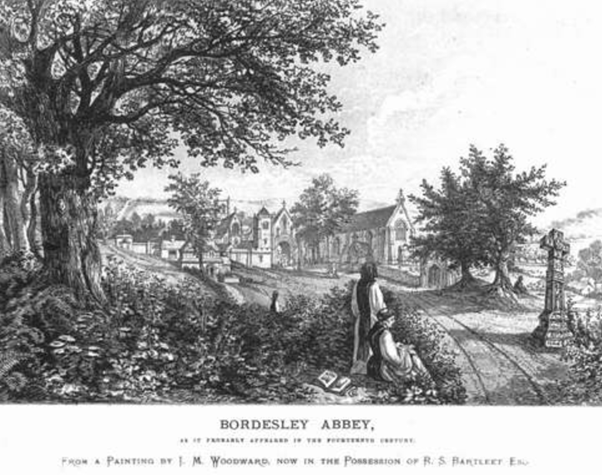

Plate 5: One of the many beautiful etchings produced by Buck for the excavator M Woodward, which imagines how Bordesley Abbey may have looked in its heyday. Image © J M Woodward.

Bordesley Abbey had been built in the 12th century when a local nobleman, Waleran de Beaumont gave lands for the Abbey in 1148 (Hirst 1984). Of the Cistercian Order, it began with the intention of deploying only plain and austere decoration but which was superseded by more elaborate flourishes the following century, as fashions (and the individual desires/aesthetics of the Abbots) changed. By 1332 it comprised thirty-four monks and eight lay brothers. It survived building collapse, flood and the Black Death but could not survive the Dissolution of 1538, when one Thomas Evans secured the lease (FMNM 2025).

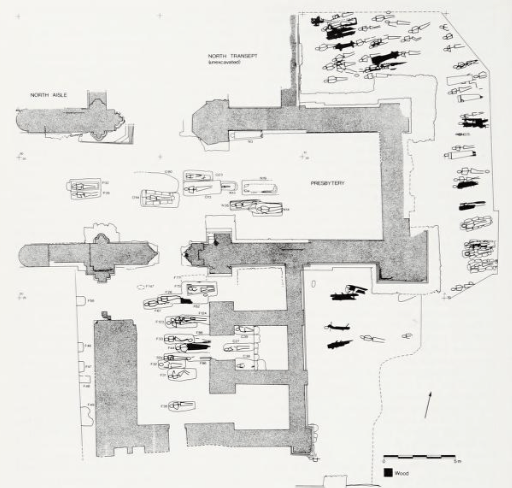

Plate 6: The proposed layout for Bordesley Abbey – the walls in black are the ones uncovered during J M Woodward’s excavations and are the ones presently on display to visitors. Plan © J M Woodward.

The first concerted excavations were carried out by James Woodard in 1864. Although undertaken in the antiquarian style, he left behind a report replete with many beautiful drawings and illustrations of the abbey and its vestiges. It remains unequalled for its attention to detail with which he recorded the artefacts. Modern excavations were undertaken in 1968 which led to a program of investigation at the site. It was found that burials of the notables associated with the Abbey had occurred within the Chapter House, one stone coffin being labelled, ‘Here lies Henry.’

Plate 7: Bordesley Abbey ruins, view to the east. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

Plate 8: Bordesley Abbey ruins, view to the west. Photo: © W Perkins 2024

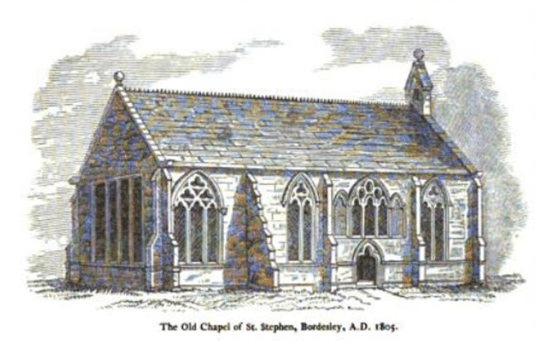

Plate 9: Rendering by Buck (c.1730) of St Stephen’s chapel included in J M Woodward’s, ‘The History of Bordesley Abbey’ (1866).

Image © J M Woodward 1866.

If one visits the little cemetery around the former chapel of St Stephen today, one is confronted by a rag-tag collection of scavenged stone blocks which had been erected as headstones following the Dissolution and the dismantling of the Abbey. The chapel served the Western Gatehouse which demarcated the west of the Abbey enclosure.

Plate 10: The collection of fragmentary headstones belonging to the now-demolished chapel of St Stephen. Photo: © W Perkins 2024

St Stephen’s Chapel

St Stephen’s Gatehouse chapel had welcomed visitors from the 12th century onwards. In the words of J M Woodward (1866), ‘The Cistercian Minsters were not intended for congregational purposes..(so therefore the chapel received).. the merchants, and the pedlers who hawked the cutlery of Sheffield or the woollen goods of Norwich, the knights-errant, and the pilgrims, who sojourned in the Abbey, on their way to or from the famous Image of Our Ladye of Worcester, the Shrine of St. Kenelm at Clent, the Holy Blood of Hailes, or the wonderful Wells at Honiley…’

After the Dissolution, the Gatehouse Chapel survived, though in a poor state. It was even used as a cattle shelter briefly. James Woodward described the graveyard in ‘The History of Bordesley Abbey’(1866) as ‘the consecrated ground wherein the forefathers of the hamlet had been buried for six centuries, (which) was let to a butcher and the fat bulls of Hereford 9who) came up into what had once been the inheritance of the Lord.’ In 1687 the parish of Tardebigge applied to the Earl of Plymouth, who had become the owner of the land, for permission to reinstate the chapel as a place of worship, and for use of the old burial ground (Woodward 1866: 94, Webbs 2024). It served the people of Redditch up to 1805 when it was demolished.

Plates 11 & 12 : Unusually, on the same headstone, two dedications, one on either side showing that it had been re-used even after it had been scavenged from the Abbey. Photo: © W Perkins 2024

‘LYETH T…

OF . ELIZA..

..E WIFE OF

…AE WI..’

and on the other side of the same stone,

‘1776’

The dedications on some of the headstones pre-date this plea for re-establishment of the right of burial, which points to the land having been (perhaps continuously) used for interment. In Woodward’s time, a decision to excavate the graves was postponed but the headstones which were found or uncovered were re-erected. It was clear to the excavators that not only were many of the stones clearly architectural elements recycled from the abbey but that many of them had seen re-use as headstones – sometimes several times!

Plate 13: Headstone, ‘D C 1724.’ Photo: © W Perkins 2024

Plate 14: Headstone (left) ‘M L 1702’ and (right) ‘L..(?).1723.’ Photo: © W Perkins 2024

Plate 15: Dedication not visible, ‘1721.’ Photo: © W Perkins 2024

Plate 16: ‘I(J)OHN G(?) DIED 1635’

Photo: © W Perkins 2024

Shoe Outline Graffiti

Whilst the improvised headstones are unusual in themselves (and may be unique) there are a number of other stones on the site which possess ’shoe outline’ graffiti. One local tale which has been circulated is that the marks are the visual representation of, ‘dancing on somebody’s grave.’ I’ve never heard this from anywhere else, so seems likely to be a fairly recent (and local) invention. Such explanations are known as an ‘illusory correlations’ whereby stories are invented to explain unknown phenomena. Similar shoe outlines are known from other graffiti corpora from all over the country, most of which are culled from churches – particularly when cut into the lead of the church’s roof.

Plate 18: Shoe outlines, one with square toe the other with a well-rounded heel-plate.

Photo: © W Perkins 2024

Graffiti Studies

In graffiti studies, many examples of shoe outlines, etched or cut into lead roofing or masonry is a common motif found among the corpora of graffiti (Swann 1996:3, Merrifield 1987: 136). In a study of medieval and historic graffiti, shoe outlines were considered to be one of the universal motifs that occur all over England and throughout history (Champion 2017).

It appears that some of the apotropaic qualities believed to be enshrined in the physical object of the shoe were considered to be equally important to those who added shoe outlines to secular and ecclesiastical buildings. The phenomena of deliberately concealed shoes – often found lodged up chimneys – or hidden under the floorboards of ancient buildings – is a common find when restoration work or demolition is undertaken.

Plate 19: Shoe outlines cut into the stone bench in the porch at St Giles, Bredon.

Photo: © W Perkins 2021.

Shoe Outlines

Outlines of feet are rare, as it is in nearly all cases the shoe which has been outlined, not the human foot. Early interpretations for the phenomenon of shoe outlines were that they had been made by pilgrims visiting relics or shrines. This idea was debunked long ago, based upon the style of shoe and the fact that many carry initials and dates which are – for the most part – post-Reformation. Sometimes, the depiction of the soles of the shoes can show the division between sole and heel, as well as hobnail patterns, some with the addition of apotropaic designs (Davidson 2017: 75).

The largest collection of shoe outlines has been culled from the lead roofs of churches, where often the shoe style shows that they mainly date to between the 17th – 19th centuries. In these examples, the soles (or heels) of the shoe have been decorated with initials (one presumes of the executor) and a date. It may have been a way of memorialising an event, which was, more often than not, the repair or re-roofing of the building (Easton 2013: 40), (Champion 2017). In some instances, shoe outlines can be found in great number, which would have exceeded the number of plombiers (lead workers) required for the roofing. It is likely that aggregations can be traced back to the clergy or congregation associated with the church copying or adding to the initial assemblage created by the original workmen (Easton 2013: 40).

In some instances, a shoe is depicted two-dimensionally – when it is often found alongside other apotropaic designs. An example of this is carved into the stone lintel of the fireplace in the 16th century Ox Row Inn in Salisbury. It sits among designs of stags (in medieval art used to symbolise Christ himself), stars and a multifoil (daisy wheel) above one of the main weak points of entry into the building – the fireplace. The ‘magical’ significance of the shoe – or the long-held belief that it was a vessel for ‘good luck’ is still not fully understood but it is a motif that can be found across the world in different cultures and time periods acting as an apotropaic object (Perkins 2025:85).

Plate 20: A shoe (possibly meant to look patched and mended), alongside stags and star designs cut into the fireplace lintel of the Ox Row Inn public house, Salisbury. Photo: © W Perkins 2019.

Epilogue: The Apparition of a Black Dog at Bordesley

J M Woodward’s work at Bordesley may be the only one anywhere in the world where the excavator claimed to be the witness to a supernatural visitation!

It is clear from Woodward’s report that the work undertaken at the site had been, to some extent, prompted by its connection to the historical figure of Guy be Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, who had earned himself the title of the ‘Black Dog of Arden.’ The nickname was meant as a slur, imparted upon him by one Piers Gaveston, whom Guy subsequently beheaded! The whole story has a sensationalist slant as it was rumoured that Beauchamp had met his end as a result of poisoning – possibly instigated by the King himself! (Patin 2025).

Plate 21: Guy de Beauchamp standing over the decapitated body of Piers Gaveston. From the 15th-century Rous Rolls. Public domain.

During the excavations of the chancel a number of anthropoid stone coffins were discovered, set into the floor. These would have originally been covered with slabs and tiles. The location for the burials would have been chosen for its proximity to the High Altar – the holy of holies – which would have been considered to be the locus of ‘power’ within the Abbey.

Unfortunately, treasure seekers had got there first, as the lid to the coffin had already been removed and contents disturbed. It contained two human skulls and mixed with bones sufficient to account for at least two bodies. Woodward surmised that the sarcophagi would have been for high status individuals (the monks and lay brothers would have been interred in St Stephen’s cemetery) and this location would have been reserved for the abbots themselves. On their discovery, he asked himself whether one of the skulls may have belonged to the infamous Guy De Beauchamp, buried in a prestigious location in return for having been a major benefactor to the abbey (Woodward 1866: 95).

Plate 22: Pattern of burials at Bordesley Abbey at east end of chancel. Not only are there burials within the chancel and side chapels but observe how burials outside the building cluster around the east end. Excavation plan © Rhatz, Hirst & Wright 1983.

Plate 23: One of the stone anthropoid coffins discovered during the 19th century excavations, likely to have housed the remains of one of the Abbots of Bordesley but which had been disturbed in antiquity. Photo: © W Perkins 2024.

It is clear from Woodward’s narrative that the spectre of Guy de Beauchamp had continued to haunt the site (at least in his mind). The clearance of the south chapel of the chancel uncovered a floor of encaustic tiles, which were considered to be too valuable to leave unattended overnight. As it happened, it was Woodward’s turn to stand watch and he found himself among the ruins as darkness fell…

Plate 24: Imaginative sketch by Buck of the Black Dog and included in Woodward’s excavation report. Image: © J M Woodward.

‘It was a dark cloudy night, and the wind blew in gusts across the Abbey Meadow, bending the tall poplars by The Forge to and fro, and then dying away mournfully among the pines on Beoley Hill……the story of the Black Dog of Arden, the grim Earl of Warwick, whose bones perchance they were that had been so lately disturbed, came again and again to the mind,—his treachery, his vengeance, his murder and his burial at Bordesley Abbey…..

….St. Stephen’s clock, striking the hour of midnight, intensified rather than disturbed (my) train of thought, when a louder blast of wind caused me to raise my head—at that instant another head appeared above the heap of soil on the opposite side of the Chapel—it was the head of a large black dog….it looked at me for a moment, and then disappeared. I seized a crow-bar, and climbed to the top of the mound, but my visitor was gone.’

J M Woodward 1866

Certainly, Woodward’s inclusion of this event in his report ranks as one of the strangest in archaeological history! However, if the author can be forgiven, you will find his report to be both rich in illustration and detail, if lacking in the modern scientific methods that would be used on a site today. It reads very much like an antiquary’s journal (which it was, essentially) but is really worth the time – I have included a link below which will take you to the digitised version of the original report.

Visiting the Site Today

To the visit the site today you will gain access not only to the excavated ruins of the Abbey but also to the small cemetery of St Stephen. On site there is also a small but interesting museum of finds from the excavations. There are further displays in the Victorian Forge Mill Needle Museum which once produced 90% of the worlds’ needles (FMNM 2025). Its location was chosen to take advantage of and to exploit the same watercourses associated with the River Arrow and the leats that the monks of the abbey had developed for their own mills.

A visit to the site will also allow you to see the mason’s marks the excavators found on some of the original stones of the Abbey and which have been organised into a ‘hunt’ for younger visitors.

Plate 245 Leaflet for a mason’s mark trail created by the on-site museum at Bordesley Abbey. © Forge Needle Museum.

If you do decide to visit Bordesley Abbey – happy hunting but…but beware of the dog!

Wayne Perkins

London July 2025.

Bibliography

British History Online (2025) Victoria County History: Bordesley Abbey

Champion, M (2015) Medieval Graffiti. Ebury Press, London

Champion, M (2017) English Medieval Graffiti Survey: Volunteer Handbook.

http://www.medieval-graffiti.co.uk

Davidson, H (2017) Holding the Sole: Shoes, Emotions and the Supernatural

Easton, T (2013) ‘Four Spiritual Middens in Mid Suffolk, England ca.1650 – 1850’ in, Historical Archaeology 47(1) pp.10-34

Forge Mill Needle Museum (FMNM) (2025) Bordesley Abbey

Hirst, S (2020) Bordesley Abbey. Visitor pamphlet. Redditch Development Corporation.

Historic England (2025) Bordesley Abbey

Lacquer, T (1983) Bodies, death & Pauper Funerals. Representations no.1. February 1983 pp.109-131.

https://www.academia.edu/90795255/Bodies_Death_and_Pauper_Funerals

Merrifield, R (1987) ‘The Archaeology of Ritual & Magic.’ BT Batsford Ltd, London

Patin Jr, J F (2025) Guy de Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick

https://www.geni.com/people/Guy-de-Beauchamp-10th-Earl-of-Warwick/6000000005858685119

Perkins, W (2025) A Consensus of Symbols: Patterns in Ritual Building Protection. Aeon Books. Forthcoming

Swann, J (1996) ‘Shoes Concealed in Buildings’ in, Costume No.30 pp.56-69

Webbs (2025) St Stephens AD 1138 – 1880

https://www.webbsredditch.co.uk/Chapter%201/St%20Stephens.html

Woodward, J M (1866) The History of Bordesley Abbey, in the Valley of the Arrow, Near Redditch, Worcestershire. J H & J Parker.

Worcestershire & Dudley Historic Churches Trust (2025) St James, Bishampton

Further Reading

Astill, G G (1983) A Medieval Industrial Complex and Its Landscape : The Metalworking Watermills and Workshops of Bordesley Abbey. CBA research paper.

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://woolmerforest.org.uk/E-Library/A/A%20MEDIEVAL%20INDUSTRIAL%20COMPLEX%20AND%20ITS%20LANDSCAPE%20-%20THE%20METALWORKING%20WATERMILLS%20AND%20WORKSHOPS%20OF%20BORDESLEY%20ABBEY.pdf

Coppack, G (1990) English Heritage Book of Abbeys & Priories. English Heritage.

https://archive.org/details/englishheritageb0000copp_p7x0/page/24/mode/2up

Duncan, M (2002) Archaeological Observations at Bordesley Abbey, Redditch, Worcestershire. Fieldwork Reference Number 31907 . Birmingham University Field Archaeology Unit

Chromeextension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-1959-1/dissemination/pdf/reports/0921.pdf

Rhatz, P, Hirst S M & Wright, S M (1983) Bordesley Abbey II. British Archaeological Reports 111.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Hugh Williams of ‘Mysteries of Mercia’ for alerting me to the headstones at Bordesley Abbey in one of his many fascinating blogs! Cheers Hugh!

Awesome!

LikeLike